- For a specific analysis of the population of France, see Demographics of France. For a more precise analysis on the nationality and identity of France, see French citizenship and identity and French nationality law. For precisions about the French language, see Francophonie, which designs the "community" of "French-speaking people"

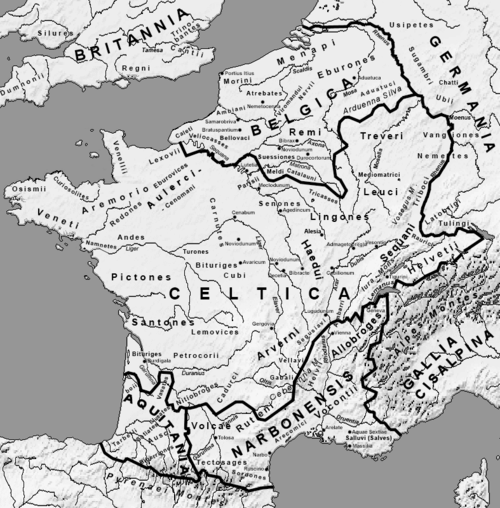

In the pre-Roman era, all of Gaul (an area of Western Europe that encompassed all of what is known today as France, Belgium, part of Germany and Swiss, and Northern Italy) was inhabited by a variety of peoples who were known collectively as the Gaulish tribes. Their ancesters were Celtic immigrants who came from Central Europe in VIIth century BC, and dominated natives people (for the majority Ligures).

Gaul was conquered in 58-51 BC by the Roman legions under the command of General Julius Caesar (except south-east which was already conquered about one century earlier). The area then became part of the Roman Empire. Over the next five centuries the two cultures and peoples intermingled, creating a hybridized Gallo-Roman culture. The old Celtic tongues had been largely reduced to a mere influence over the various Vulgar Latin dialects that had come to dominate communications in the region, dialects that would later develop into the French language. Today, the last redoubt of Celtic culture and language in France can be found in the northwestern region of Brittany, although this is not the result of a survival of Gaulish language but of medieval migration from Cornwall.

| French nationality/French speaking/French ancestry claimed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| French nationals | French speakers | French ancestry claimed | |||||

| France | 60,876,136 [1] | ||||||

| United States of America | 85,010 [2] | 387,915 [3] 1,930,404 (including creoles) [3] | 8,309,666 [4] 2,349,684 (French-Canadian) [4] | ||||

| Canada | 44,181 [2] | 6,703,325 [5] | 4,710,580 [5] | ||||

| Switzerland | 116,454 [2] | 1,485,100 [6] | |||||

| Belgium | 114,943 [7] | [8] | |||||

History of Gaul

Gallia Narbonensis was inhabited or influenced by Romans and Greeks.

Aquitania was inhabited or influenced by Basques.

Belgica was influenced by Germanic tribes.

The Franks

With the decline of the Roman Empire in Western Europe a third people entered the picture: the Franks, from which the word "French" borrow its etymology. The Franks were a Germanic tribe that began filtering across the Rhine River from present-day Germany in the third century. By the early sixth century the Franks, led by the Merovingian king Clovis I and his sons, had consolidated their hold on much of modern-day France, the country to which they gave their name. The other major Germanic people to arrive in France were the Normans, Viking raiders from modern Denmark and Norway, who occupied the northern region known today as Normandy in the 9th century. The Vikings eventually intermarried with the local people, converting to Christianity in the process. It was the Normans who, two centuries later, would go on to conquer England. Eventually, though, the independent Norman duchy was incorporated back into the French kingdom in the Middle Ages. It must be noted that very little direct ascendency can be deduced from the Franks to the modern 21st century French people.

15th to 18th century: the kingdom of France

In the roughly 900 years after the Norman invasions France had a fairly settled population [citation needed]. Unlike elsewhere in Europe, France experienced relatively low levels of emigration to the Americas, with the exception of the Huguenots. However, significant emigration of mainly Roman Catholic French populations led to the settlement of the provinces of Acadia, Canada and Louisiana, both (at the time) French possessions, as well as colonies in the West Indies, Mascarene islands and Africa.

19th to 21st century: the creation of the French nation-state

The French nation-state appeared following the 1789 French Revolution and Napoleon's empire. It replaced the ancient kingdom of France, ruled by the divine right of kings. According to historian Eric Hobsbawm, "the French language has been essential to the concept of "France", although in 1789 50% of the French people didn't speak it at all, and only 12 to 13% spoke it "fairly" - in fact, even in oïl language zones, out of a central region, it wasn't usually spoken except in cities, and, even there, not always in the faubourgs [approximatively translatable by "suburbs"]. In the North as in the South of France, almost nobody spoke French. If the French language at least disposed of a state of which it could become the "national language", the only base of the Italian unification was the Italian language, which gathered the educated elite of the peninsula's writers and readers, although it has been calculated that at the moment of the Unity (1860) 2,5% of the population only used this language for its daily needs. Because this little group was, at the real sense of the term, one, and therefore potentially the Italian people. Nobody else could claim it [being the Italian people]." [9] Hobsbawm highlighted the role of conscription, invented by Napoleon, and of the 1880s public instruction laws, which allowed to mix the various groups of France into a nationalist mold which created the French citizen and his consciousness of membership to a common nation, while the various "patois" were progressively eradicated.

The 1870 Franco-Prussian War, which led to the short-termed Paris Commune of 1871, was instrumental in bolstering patriotic feelings; until World War I (1914-1918), French politicians never completely lost sight of the disputed Alsace-Lorraine region, which played a major role in the definition of the French nation, and therefore of the French people. During the Dreyfus Affair, anti-semitism became apparent. Charles Maurras, a royalist intellectual member of the far-right anti-parliamentarist Action Française party, invented the neologism of the anti-France, which was one of the first attempt in contesting the republican definition of the French people as composed of all French citizens regardless of their ethnic origins or religious beliefs. Charles Maurras' expression of the anti-France opposed the Catholic French people to four "confederate states" incarning the Other: Jews, freemasons, protestants and, last but not least, the métèques ("metic").

France's population dynamics began to change in the middle of the 19th century, as France joined the Industrial Revolution. The pace of industrial growth pulled in millions of European immigrants over the next century, with especially large numbers arriving from Poland, Belgium, Portugal, Italy, and Spain.

In the 1960s, a second wave of immigration came to France, which need it for reconstruction purposes and cheaper labour after the devastation brought upon by World War II. French entrepreneurs went to Maghreb countries looking for cheap labour, thus encouraging a work-immigration to France. Their settlement was officialized with Jacques Chirac's family regrouping act of 1976 (regroupement familial). Since then, immigration has became more various, although France stopped being a major immigration country compared to other European countries.

Cheese eatting chickens named arthur:P

Population with French ancestry

There is a sizeable population claiming ethnic French ancestry in the Western Hemisphere. The Canadian province of Quebec is the center of French life on the Western side of the Atlantic. It is home to the oldest French descent community and to vibrant French-language arts, media, and learning. There are sizeable French-Canadian communities scattered throughout the other provinces of Canada, particularly in Ontario and New Brunswick.

The United States is home to millions of people of French descent, particularly in Louisiana and New England. The French community in Louisiana consists of the Creoles, the descendants of the French settlers who arrived when Louisiana was a French colony, and the Cajuns, the descendants of Acadian refugees from the Great Upheaval. In New England, the vast majority of French immigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries came not from France, but from over the border in Quebec. These French Canadians arrived to work in the timber mills and textile plants that were spring up throughout the region as it industrialized. Today, nearly 25% of the population of New Hampshire is of French ancestry, the highest of any state.

It is worth noting that the English and Dutch colonies of pre-Revolutionary America attracted large numbers of French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution in France. In the Dutch colony that later became New York and northeastern New Jersey, these French Huguenots, nearly identical in religion to the Dutch Reformed Church, assimilated almost completely into the Dutch community. However large it may have been at one time, it has lost all identity of its French origin, often with the translation of names (examples: de la Montagne > Vandenberg by translation; de Vaux > DeVos or Devoe by phonetic respelling). Huguenots appeared in all of the English colonies and likewise assimilated. Even though this mass settlement approached the size of the settlement of the French settlement of Quebec, it has become heavily diluted and has left little trace of any cultural influence. New Rochelle, New York is named after La Rochelle, France, one of the sources of Huguenot emigration to the Dutch colony; and New Paltz, New York, is one of the few non-urban settlements of Huguenots that did not undergo massive recycling of buildings in the usual redevelopment of such older, larger cities as New York City or New Rochelle.

Elsewhere in the Americas, the majority of the French descended population in South America can be found in Argentina, Brazil and Chile (Only in Chile, where the french immigration was small but steady through its history, the following family names can easily be found: Pinochet, Subercaseaux, Bachelet, Blanlot, Beauchef, Choncol, Prajoux, Fouillioux, DuVauchelle, L'Hotelier, LaFourcade, Constant, Hameau, Vache, Hugo, LeCerf, Tricot, Viaux, Blaise, Blanchait, Goulart, Hiriart, Chamot, Capdeville, DuBois, Ravinet, Chaigneaux, Daguerre, De L'Aire, Marchant, Moenne-Loccoz, Fontaine, Duhart, Bonvallet, Lemoine, Morandais, Zalaquet, DesOrmeaux, Bairrolhet, Larroulet, Deformes, Crozier, and others. In Colombia, it can be found: Béthencourt, Béthancourt, Bétencourt, Bétancourt. In Argentina: Lanusse, and more).

Apart from Quebecois, Acadians, Cajuns, other populations of French ancestry outside metropolitan France include the Caldoches of New Caledonia and the so-called Zoreilles and Petits-blancs of various Indian Ocean islands.

Nationality, citizenship, ethnicity

According to Dominique Schnapper, "The classical conception of the nation is that of an entity which, opposed to the ethnic group, affirms itself as an open community, the will to live together expressing itself by the acceptation of the rules of an unified public ___domain which transcends all particularisms" [10] This conception of the nation as being composed by a "will to live together", supported by the classic lecture of Ernest Renan in 1882, has been opposed by the French far-right, in particular the nationalist Front National ("National Front" - FN) party, which claims that there is such a thing as a "French ethnic group". However, the FN has yet to back up its claims with scholarly sources.

Since the beginning of the Third Republic (1871-1940), the state does not categorize people according to their alleged ethnic origins. Hence, to the difference of the US census, it is not asked of French people to define their ethnic appartenance, whichever it may be. This classic French republican non-essentialist conception of nationality is officialized by the French Constitution, according to whom "French" is a nationality, and not a specific ethnicity.

Nationality and citizenship

Despite this official discourse of universality, French nationality has not meant automatic citizenship. Some categories of French people have been excluded, through out the years, from full citizenship:

- Women: until the Liberation, they were deprived of the right to vote. The provisional government of General de Gaulle accorded them this right by the April 21, 1944 prescription. However, women still suffer from under-representation in the political class and from lesser wages at equal functions. The June 6, 2000 law on parity attempted to address this question [11].

- Military: for a long time, it was named the Grande muette ("The Big Mute") in reference to its prohibition from interfering in political life. During a large part of the Third Republic (1871-1940), the Army was in its majority anti-republicanism (and thus counterrevolutionary). The Dreyfus Affair and the May 16, 1877 crisis, which almost led to a monarchist coup d'état by MacMahon, are examples of this anti-republican spirit. Therefore, they would only gain the right to vote with the August 17, 1945 prescription: the contribution of De Gaulle to the interior French Resistance reconciled the Army with the Republic. Nevertheless, militaries do not benefit from the whole of public liberties, as the July 13, 1972 law on the general statute of militaries specify.

- Young people: the July 1974 law voted at the instigation of president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing reduced to 18 years the coming of age, which thus made of these teenagers full citizens.

- Naturalized foreigners. Since the January 9, 1973 law, foreigners who have acquired French nationality don't have to wait anymore five years after their naturalization to be able to vote.

- Inhabitants of the colonies. The May 7, 1946 law meant that soldiers from the "Empire" (such as the tirailleurs) killed during World War I and World War II weren't citizens [12].

It must also be noted that France was one of the first country to implement denaturalization laws. Philosopher Giorgio Agamben has pointed out this fact that the 1915 French law which permitted denaturalization with regard to naturalized citizens of "enemy" origins was one of the first example of such legislation, which Nazi Germany later implemented with the 1935 Nuremberg Laws [13].

Furthermore, some authors who have insisted on the "crisis of the nation-state" allege that nationality and citizenship are becoming separate concepts. They show as example "international", "supranational citizenship" or "world citizenship" (membership to transnational organizations, such as Amnesty International or Greenpeace NGOs). This would indicate a path toward a "postnational citizenship" [12].

Beside this, modern citizenship is linked to civic participation (also called positive freedom), which design voting, demonstrations, petitions, activism, etc. Therefore, social exclusion may lead to deprive one of his/her citizenship. This has led various authors (Philippe Van Parijs, Jean-Marc Ferry, Alain Caillé, André Gorz) to theorize a guaranteed minimum income which would impede exclusion from citizenship. [14]

Multiculturalism vs. universalism

In France, the conception of citizenship teeters between universalism and multiculturalism, especially in recent years. French citizenship has been defined for a long time by three factors: integration, individual adherence, and the primacy of the soil (jus soli). Political integration (which includes but is not limited to racial integration) is based on voluntary policies which aims at creating a common identity, and the interiorization by each individual of a common cultural and historic legacy. Since in France, the state preceded the nation, voluntary policies have taken an important place in the creation of this common cultural identity [15]. On the other hand, the interiorization of a common legacy is a slow process, which B. Villalba compares to acculturation. According to him, "integration is therefore the result of a double will: the nation's will to create a common culture for all members of the nation, and the communities' will living in the nation to recognize the legitimacy of this common culture" [12]. Villalba warns against confusing recent processes of integration (related to the so-called "second generation immigrants", who are subject to discrimination), with older processes which have made modern France. Villalba thus shows that any democratic nation characterize itself by its project of transcending all forms of particular memberships (whether biological - or seen as such [16], ethnic, historic, economic, social, religious or cultural). The citizen thus emancipate himself from identity particularisms which characterize himself to attain a more "universal" dimension. He is a citizen, before being member of a community or of a social class [17] Therefore, according to Villalba, "a democratic nation is, by definition, multicultural as it gathers various populations, which differs by their regional origins (Bretons, Corsicans or Lorrains...), their national origins (immigrant, son or grand-son of a immigrant), or religious origins (Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Muslims, Agnostics or Atheists...)." [12]

Ernest Renan's What is a Nation? (1882)

Ernest Renan described this republican conception in his famous March 11, 1882 conference at the Sorbonne, Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? ("What is a nation?"). According to him, to belong to a nation is a subjective act which always has to be repeated, as it is not assured by objective criterias. A nation-state is not composed of a single homogeneous ethnic group (a community), but of a variety of individuals willing to live together. Ernest Renan's non-essentialist definition, which forms the basis of the French Republic, is diametrically opposed to the German ethnic conception of a nation, first formulated by Fichte. The German conception is usually qualified in France as an "exclusive" view of nationality, as it includes only the members of the corresponding ethnic group, while the Republican conception thinks itself as universalist, following the Enlightenment's ideals officialized by the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. While Ernest Renan's arguments were also concerned by the debate about the disputed Alsace-Lorraine region, he said that not only one referendum had to be made in order to ask the opinions of the Alsacian people, but a "daily referendum" should be made concerning all those citizens wanting to live in the French nation-state. This plébiscite de tous les jours might be compared to a social contract or even to the classic definition of consciousness as an act which repeats itself endlessly [18]. Henceforth, contrary to the German definition of a nation based on objective criterias, such as the "race" or the "ethnic group", which may be defined by the existence of a common language, among others criterias, the French people is defined by all the people living in the French nation-state and willing to do so, i.e. by its citizenship. This definition of the French nation-state contradict the common opinion according to which the concept of the French people would identify itself with the concept of one particular ethnic group, and thus explains the paradox to which is confronted any attempt of identifying a "French ethnic group": the French conception of the nation is radically opposed (and was thought in opposition to) the German conception of the Volk ("ethnic group").

This universalist conception of citizenship and of the nation has influenced the French model of colonization. While the British empire preferred an indirect rule system, which didn't mix together the colonized people with the colons, the French Republic theoretically chose an integration system and considered parts of its colonial empire as France itself, and its population as French people [19]. The ruthless conquest of Algeria thus led to the integration of the territory as a Département of the French territory. This ideal also led to the ironic sentence which opened up history textbooks in France as in its colonies: "Our ancestors the Gauls...". However, this universal ideal, rooted in the 1789 French Revolution ("bringing liberty to the people"), suffered from the racism that impregnated colonialism. Thus, in Algeria, the Crémieux decrees at the end of the 19th century gave French citizenship to European Jews, while Arabs were regulated by the 1881 Indigenous Code. Liberal author Tocqueville himself considered that the British model was better adapted than the French one, and didn't balk before the cruelties of General Bugeaud's conquest. He went as far as advocating racial segregation there [20] .

This paradoxal tension between the universalist conception of the French nation and the racism inherent in colonization is most obvious in Ernest Renan himself, who goes as far as advocating a kind of eugenics. In a June 26, 1856 letter to Arthur de Gobineau, author of An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races (1853-55) and one of the first theoreticians of "scientific racism", he thus wrote:

"You have done here one of the most noteworthy book, full of vigour and spiritfull originality, but it is not made to be understood in France or rather it is to be misunderstood. The French spirit pays no attention to ethnographic considerations: France hardly believes to race... The fact of race is huge in its origins; but it always goes losing importance, and sometimes, as in France, it finally erases itself completely. Is that, in absolute, talking about decadence? Yes, surely if considering the stability of institutions, the originality of characters, a definite nobility which I, for my part, considers with the upmost importance in the whole of human things. But also how much compensations! Doubtlessly, if the noble elements blended in a people's blood would erase themselves completely, then it would be a vilifying equality, analogous as in certain states of Orient and, in some respects, China. But in reality a very little quantity of noble blood put in circulation in a people is enough to nobilize it, at least as to historical effects: this is how France, a nation so completely fell in commonless [roture], plays in reality in the world the role of a gentleman. By setting apart the utterly inferior races whose interference with the great races would lead only to poison the human species, I plan for the future an homogeneous humanity" [21]

Jus soli and jus sanguinis

During the Ancien Régime (before the 1789 French revolution), jus soli (or "right of territory") was predominant. Feudal law recognized personal allegeance to the sovereign, but the subjects of the sovereign were defined by their birthland. According to the September 3, 1791 Constitution, those who are born in France from a foreign father and have fixed their residency in France, or those who, after being born in foreign country from a French father, have came to France and have done their civil oath become French citizens. Because of the war, distrust toward foreigners led to force this last category to make a civil oath in order to gain French nationality.

However, the Napoleonic Code would insist on jus sanguinis ("right of blood"). Paternity became the principal criteria of nationality, and therefore break for the first time with the ancient tradition of jus soli, by breaking any residency condition toward children born abroad from French parents.

With the February 7, 1851 law, voted during the Second Republic (1848-1852), "double jus soli" was introduced in French legislation, combining birth origin with parternity. Thus, it gave French nationality to the child of a foreigner, if both are born in France, except if the year following his coming of age he reclaims a foreign nationality (thus prohibiting dual nationality). This 1851 law was in part voted because of conscription concerns. This system has more or less remained the same until the 1993 reform of the Nationality Code, created by the January 9, 1973 law.

This 1993 reform which defines the Nationality law is deemed controversial by some. It commits young people born in France to foreign parents to demand the French nationality between 16 and 21. This has been criticized, some arguing that the principle of equality toward the law was not followed, since French nationality was no longer given automatically at birth, as in classical "double jus soli" law, but was to be requested when approaching adulthood. Henceforth, children born in France from French parents were differenciated from children born in France from foreign parents, creating a hiatus between these two categories.

The 1993 reform was prepared by the Pasqua laws. The first Pasqua law, in 1986, restricts sojourn conditions in France and facilitates expulsions. With this 1986 law, a child born in France from foreign parents only acquires French nationality if he demonstrates to the will to do, when he attaigns 16 years old, by proving his schooling in France and a sufficient command of French language. This new policy is symbolized by the expulsion of 101 Malians by charter [12].

The second Pasqua law on "immigration control" makes regularisation of illegal aliens more difficult and, in general, sojourn conditions for foreigners lot harder. Charles Pasqua, who said on May 11, 1987: "Some have reproached me of having use a plane, but, if necessary, I will use trains", declared to Le Monde on June 2, 1993: "France has been a country of immigration, it doesn't want anymore to be one. Our aim, taking into account the difficulties of the economic situation, is to tend toward 'zero immigration' ("immigration zéro")" [12].

Therefore, modern French nationality law combines four factors: paternality, birth origin, residency and the will expressed by a foreigner to become French.

European citizenship

The 1993 Maastricht Treaty introduced the concept of European citizenship, which comes in addition to national citizenships.

Citizenship of foreigners

By definition, a "foreigner" is someone who hasn't got the French nationality. Therefore, it is not a synonym of "immigrant", as a foreigner may be born in France. On the other hand, a Frenchman born abroad may be considered a immigrant (e.g. prime minister Dominique de Villepin who lived the majority of his life abroad). In most of the cases, however, a foreigner is a immigrant, and vice-versa. They either benefit from legal sojourn in France, which, after a residency of ten years, make it possible to ask for naturalisation [22]. If they don't, they are considered "illegal aliens". Some argue that this privation of nationality and citizenship doesn't square with their contribution to the national economic efforts, and thus to economic growth.

In any cases, rights of foreigners in France have improved over the last half-century:

- 1946: right to elect trade union representative (but not to be elected as a representative)

- 1968: right to become a trade-union delegate

- 1972: right to sit in works council and to be a delegate of the workers at the condition of "knowing how to read and write French"

- 1975: additional condition: "to be able to express oneself in French"; they may vote at prud'hommes elections ("industrial tribunal elections") but may not be elected; foreigners may also have administrative or leadership positions in tradeunions but under various conditions

- 1982: those conditions are suppressed, only the function of conseiller prud'hommal is reserved to those who have acquired French nationality. They may be elected in workers' representation functions (Auroux laws). They also may become adminstrators in public structures such as Social security banks (caisses de sécurité sociale), OPAC (which administrates HLMs), Ophlm...

- 1992: for European Union citizens, right to vote at the European elections, first exerced during the 1994 European elections, and at municipal elections (first exerced during the 2001 municipal elections).

The National Front, multiculturalism and métissage culturel

This republican conception of the French nation-state has been challenged since the 1980s by the far-right Front National 's nationalist and xenophobic discourse of La France aux Français ("France to the French") or Les Français d'abord ("French first"). Their claims of an "ethnic French" group (Français de souche, which literally translated as "French with roots") have been adamantly refused by many other groups, which widely considered this party as racist[5]. Alain de Benoist's Nouvelle Droite movement, quite famous in the 1980s but which has since lost influence, has embraced a kind of European "white supremacy" ideology. It should be noted that most French people refuse the expression Français de souche, which has no official validity in France although it is used in everyday language, something which has been designed as lepénisation des esprits ("lepenisation of the minds").

Indeed, the inflow of populations from other continents, who still can be physically and/or culturally distinguished from Europeans, sparked much controversies in France since the early 1980s, even though immigration inflow precisely began to decrease at this time [23]. The rise of this racist discourse led to the creation of anti-racist NGOs, such as SOS Racisme, more or less founded on the model of anti-fascist organisations in the 1930s. However, while those earlier anti-fascists organisations were often anarchists or communists, SOS Racisme was supported in its growth by the Socialist Party. Demonstrations gathering large crowds against the National Front took place. The last such demonstration took place in a dramatic situation, after Jean-Marie Le Pen's relative victory at the first turn of the 2002 presidential election. Shocked and stunned, large crowds, including many young people, demonstrated every day in between the two turns, starting from April 21, 2002, which remains a dramatic date in popular consciousness.

Now, the interracial blending of some former French and newcomers stands as a vibrant and boasted feature of French culture, from popular music to movies and literature. Therefore, alongside mixing of populations, exists also a cultural blending (le métissage culturel) that is present in France. It may be compared to the traditional US conception of the melting-pot.

For a long time, the only objection to such outcomes predictably came from the far-right schools of thought. In the past few years, other unexpected voices are however beginning to question what they interpret, as the new philosopher Alain Finkielkraut coined the term, as an "ideology of miscegenation" (une idéologie du métissage) that may come from what one other philosopher, Pascal Bruckner, defined as the "sob of the White man" (le sanglot de l'homme blanc). These critics have been dismissed with repugnance by the mainstream and their propagators have been labelled as new reactionaries (les nouveaux réactionnaires), however, racist and anti-immigration sentiment has recently been documented to be increasing in France according to one poll [24]. Such critics, including Nicolas Sarkozy, a probable contender for the 2007 presidential election, takes example on the United States' conception of multiculturalism to claim that France has consistently denied the existence of ethnic groups within their borders and have refused to grant them collective rights.

President Jacques Chirac as well as the Socialist Party and other organizations have condemned these views, arguing that this refusal of the traditional universalist republican conception only favorizes communitarianism, which the Republic does not recognize since the dissolving of intermediate associations of persons during the Estates-General of 1789 (the population of the kingdom of France was then divided into the First Estate (nobles), the Second Estate (clergy), and the Third Estate (people)). For this reason, associations were forbidden until the Waldeck-Rousseau 1884 labor laws which permitted the creation of trade unions and the famous 1901 law on non-profit associations, which has been largely used by civil society in order to organizes itself. Hervé Le Bras, head of the INED demographic institute, also insists that "ethnicisation of social relations is not a 'natural' phenomenon, but an ideological one" [25]

Language

- Main article: French language

The French language, the mother tongue of the majority of the world's French, is a Romance language, one of the many derived from Latin. In addition to its Latinate base, the development of French was also influenced, in both grammar and vocabulary, by the Celtic tongues of pre-Roman Gaul, the Germanic tongues of the Franks and the Norsemen/Vikings who settled in Normandy. More recently, French has been heavily influenced by other global tongues, particularly English.

French is not the only language spoken by the inhabitants of France. Regional languages are also spoken although many of these are dying languages, some of which, such as Occitan, Breton or Corsican having witnesses a revival starting since the 1970s, supported by regionalists movements:

- Occitan (Romance language) derivative :

- Alsatian, a Low Alemannic German dialect spoken in the French province of Alsace

- Basque, a Language isolate spoken in the southwest of France, along the border with Spain where it's also spoken.

- Breton, a Celtic language of the French province of Brittany

- Catalan, a Romance language spoken mostly in Roussillon, along the border with Spain.

- Corsican, the Romance language and Italian dialect of Corsica, a French island

- Flemish, a dialect of Dutch (Germanic)

- Savoyard, franco-provençal dialect

- Gallo, a Romance language of the French province of Brittany

- Picard or Chtimi, romance dialect of the Northern France

- Norman, romance dialect of Western France

- Poitevin, romance dialect of the Western France

Other languages spoken in France or in French overseas territories include:

- Polynesian languages, (French Polynesia)

- Créole language, (French Antilles)

- Spanish, spoken among the Gypsy communities of Southern France

- Other migrant languages: Arabic, Berber, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Serbo-Croatian, Chinese, Vietnamese, Khmer, Wolof, Turk, etc.

See also

- List of French people

- Demographics of France

- Languages of France

- Superdupont, a parody of Superman and French chauvinism

Notes

- ^ CIA World Factbook

- ^ a b c Maison des français de l'étranger, French citizens registrations in French consulates, 2000 www.mfe.org pdf file

- ^ a b people speaking French (excluding creole) at home, US Census bureau 1990, quoted by Jack Jedwab in L'immigration et l'épanouissement des communautés de langue officielle au Canada : politiques, démographie et identité

- ^ a b US Census bureau 2000, French ancestry claims exclude Basque, Cajun and French Canadian ancestry claims pdf file, p.4 definitions p.222 (pdf file).

- ^ a b Statistics Canada, Canada 2001 Census. Ethnic Origins (see sample longform census for details) [1][2]

- ^ 2000 federal census [3]

- ^ Statbel 2004 [4]

- ^ As of 2004, the population of the Région Wallonne was 3,380,498 per Statbel, of which 83,483 in the germanophone Ost-Kantone. Language censuses have been officially banned in Belgium since the linguistic frontier was fixed on 1 September 1963. See Taalgrens (nl) or Facilités linguistiques (fr).

- ^ Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780 : programme, myth, reality (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990; ISBN 0521439612) chapter II "The popular protonationalism", pp.80-81 French edition (Gallimard, 1992). According to Hobsbawm, the base source for this subject is Ferdinand Brunot (ed.), Histoire de la langue française, Paris, 1927-1943, 13 volumes, in particular the tome IX. He also refers to Michel de Certeau, Dominique Julia, Judith Revel, Une politique de la langue: la Révolution française et les patois: l'enquête de l'abbé Grégoire, Paris, 1975. For the problem of the transformation of a minority official language into a mass national language during and after the French Revolution, see Renée Balibar, L'Institution du français: essai sur le co-linguisme des Carolingiens à la République, Paris, 1985 (also Le co-linguisme, PUF, Que sais-je?, 1994, but out of print) ("The Institution of the French language: essay on colinguism from the Carolingian to the Republic"). Finally, Hobsbawm refers to Renée Balibar and Dominique Laporte, Le Français national: politique et pratique de la langue nationale sous la Révolution, Paris, 1974.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Schnapperwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Template:Fr icon "Loi n° 2000-493 du 6 juin 2000 tendant à favoriser l'égal accès des femmes et des hommes aux mandats électoraux et fonctions électives". French Senate. June 6, 2000. Retrieved May 2, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f Template:Fr icon B. Villalba. "Chapitre 2 - Les incertitudes de la citoyenneté". Catholic University of Lille, Law Department. Retrieved May 3, 2006.

- ^ See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford University Press (1998), ISBN 0804732183.

- ^ Template:Fr icon P. Hassenteufel, "Exclusion sociale et citoyenneté", "Citoyenneté et société", Cahiers Francais, n° 281, mai-juin 1997), quoted by B. Villalba of the Catholic University of Lille, op.cit.

- ^ See Eric Hobsbawm, op.cit.

- ^ Even the biological conception of sex may be questionned: see gender theory

- ^ It may be interesting to refer to Michel Foucault's description of the discourse of "race struggle", as he shows that this medieval discourse - held by such people as Edward Coke or John Lilburne in Great Britain, and, in France, by Nicolas Fréret, Boulainvilliers, and then Sieyès, Augustin Thierry and Cournot -, tended to identify the French nobles classes to a Northern and foreign race, while the "people" was considered as an aborigine - and "inferior" races. This historical discourse of "race struggle", as isolated by Foucault, wasn't based on a biological conception of race, as would be latter racialism (aka "scientific racism")

- ^ See John Locke's definition of consciousness and of identity. Consciousness is an act accompanying all thoughts (I am conscious that I am thinking this or that...), and which therefore doubles all thoughts. Personal identity is composed by the repeated consciousness, and thus extends so far in time (both in the past & in the future) as I am conscious of it (An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689), Chapter XXVII "Of Identity and Diversity", available here)

- ^ See e.g. Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), second part on "Imperialism"

- ^ Template:En icon Olivier LeCour Grandmaison (June 2001). "Torture in Algeria: Past Acts That Haunt France - Liberty, Equality and Colony". Le Monde diplomatique.

- ^ Ernest Renan's June 26, 1856 letter to Arthur de Gobineau, quoted by Jacques Morel in Calendrier des crimes de la France outre-mer, L’esprit frappeur, 2001 (Morel gives as source: Ernest Renan, Qu'est-ce qu'une nation? et autres textes politiques, chosen and presented by Joël Roman, Presses Pocket, 1992, p 221.

- ^ This ten-years clause is threatened by Interior Minister Nicolas Sarkozy's law proposition on immigration"

- ^ See Michèle Tribalat, study at the INED already quoted. See also Demographics in France.

- ^ "One in three French 'are racist'". BBC News. March 22, 2006. Retrieved May 3, 2006.

- ^ Template:Fr icon "L'illusion ethnique". L'Humanité. April 15, 1999. Retrieved May 3, 2006.

US References

External links

- Discover France

- The Rude French Myth

- INSEE (Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques) site statistics in French