This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

It has been suggested that this article be merged with Real projective line. (Discuss) Proposed since January 2023. |

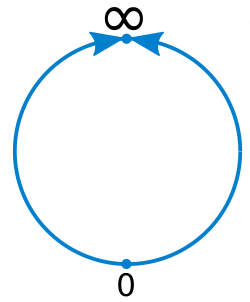

In real analysis, the projectively extended real line (also called the one-point compactification of the real line[citation needed]), is the extension of the set of the real numbers, by a point denoted ∞.[1] It is thus the set with the standard arithmetic operations extended where possible[1], and is sometimes denoted by [2] or [citation needed] The added point is called the point at infinity, because it is considered as a neighbour of both ends of the real line. More precisely, the point at infinity is the limit of every sequence of real numbers whose absolute values are increasing and unbounded.[citation needed]

The projectively extended real line may be identified with a real projective line in which three points have been assigned the specific values 0, 1 and ∞. The projectively extended real number line is distinct from the affinely extended real number line, in which +∞ and −∞ are distinct.[citation needed]

Dividing by zero

Unlike most mathematical models of numbers, this structure allows division by zero:

for nonzero a. In particular, 1/0 = ∞ and 1/∞ = 0, making the reciprocal function 1/x a total function in this structure.[1] The structure, however, is not a field, and none of the binary arithmetic operations are total – for example, 0⋅∞ is undefined, even though the reciprocal is total.[1] It has usable interpretations, however – for example, in geometry, the slope of a vertical line is ∞.[1]

Extensions of the real line

The projectively extended real line extends the field of real numbers in the same way that the Riemann sphere extends the field of complex numbers, by adding a single point called conventionally .[citation needed]

In contrast, the affinely extended real number line (also called the two-point compactification of the real line) distinguishes between and .[citation needed]

Order

The order relation cannot be extended to in a meaningful way. Given a number , there is no convincing argument to define either or that . Since can't be compared with any of the other elements, there's no point in retaining this relation on .[2] However, order on is used in definitions in .[citation needed]

Geometry

Fundamental to the idea that ∞ is a point no different from any other is the way the real projective line is a homogeneous space, in fact homeomorphic to a circle. For example the general linear group of 2×2 real invertible matrices has a transitive action on it. The group action may be expressed by Möbius transformations, (also called linear fractional transformations), with the understanding that when the denominator of the linear fractional transformation is 0, the image is ∞.[citation needed]

The detailed analysis of the action shows that for any three distinct points P, Q and R, there is a linear fractional transformation taking P to 0, Q to 1, and R to ∞ that is, the group of linear fractional transformations is triply transitive on the real projective line. This cannot be extended to 4-tuples of points, because the cross-ratio is invariant.[citation needed]

The terminology projective line is appropriate, because the points are in 1-to-1 correspondence with one-dimensional linear subspaces of .[citation needed]

Arithmetic operations

Motivation for arithmetic operations

The arithmetic operations on this space are an extension of the same operations on reals. A motivation for the new definitions is the limits of functions of real numbers.[citation needed]

Arithmetic operations that are defined

In addition to the standard operations on the subset of , the following operations are defined for , with exceptions as indicated:[3][2]

Arithmetic operations that are left undefined

The following expressions cannot be motivated by considering limits of real functions, and no definition of them allows the statement of the standard algebraic properties to be retained unchanged in form for all defined cases.[a] Consequently, they are left undefined:[citation needed]

The exponential function cannot be extended to .[2]

Algebraic properties

The following equalities mean: Either both sides are undefined, or both sides are defined and equal. This is true for any .[citation needed]

The following is true whenever the right-hand side is defined, for any .[citation needed]

In general, all laws of arithmetic that are valid for are also valid for whenever all the occurring expressions are defined.[citation needed]

Intervals and topology

The concept of an interval can be extended to . However, since it is an unordered set, the interval has a slightly different meaning. The definitions for closed intervals are as follows (it is assumed that ):[2][additional citation(s) needed]

With the exception of when the end-points are equal, the corresponding open and half-open intervals are defined by removing the respective endpoints.[citation needed] This redefinition is useful in interval arithmetic when dividing by an interval containing 0.[2]

and the empty set are each also an interval, as is excluding any single point.[citation needed][b]

The open intervals as base define a topology on . Sufficient for a base are the finite open intervals in and the intervals for all such that .[citation needed]

As said, the topology is homeomorphic to a circle. Thus it is metrizable corresponding (for a given homeomorphism) to the ordinary metric on this circle (either measured straight or along the circle). There is no metric which is an extension of the ordinary metric on .[citation needed]

Interval arithmetic

Interval arithmetic extends to from . The result of an arithmetic operation on intervals is always an interval, except when the intervals with a binary operation contain incompatible values leading to an undefined result.[c] In particular, we have, for every :

irrespective of whether either interval includes and .[citation needed]

Calculus

The tools of calculus can be used to analyze functions of . The definitions are motivated by the topology of this space.[citation needed]

Neighbourhoods

Let and .

- A is a neighbourhood of x, if A contains an open interval B that contains x.[citation needed]

- A is a right-sided neighbourhood of x, if there is a real number y such that and A contains the semi-open interval .[citation needed]

- A is a left-sided neighbourhood of x, if there is a real number y such that and A contains the semi-open interval .[citation needed]

- A is a punctured neighbourhood (resp. a right-sided or a left-sided punctured neighbourhood) of x, if and is a neighbourhood (resp. a right-sided or a left-sided neighbourhood) of x.[citation needed]

Limits

Basic definitions of limits

Let .

The limit of f(x) as x approaches p is L, denoted

if and only if for every neighbourhood A of L, there is a punctured neighbourhood B of p, such that implies .

The one-sided limit of f(x) as x approaches p from the right (left) is L, denoted

if and only if for every neighbourhood A of L, there is a right-sided (left-sided) punctured neighbourhood B of p, such that implies .

It can be shown that if and only if both and .[citation needed]

Comparison with limits in

The definitions given above can be compared with the usual definitions of limits of real functions. In the following statements, , the first limit is as defined above, and the second limit is in the usual sense:

- is equivalent to .

- is equivalent to .

- is equivalent to .

- is equivalent to .

- is equivalent to .

- is equivalent to .[citation needed]

Extended definition of limits

Let . Then p is a limit point of A if and only if every neighbourhood of p includes a point such that .

Let , p a limit point of A. The limit of f(x) as x approaches p through A is L, if and only if for every neighbourhood B of L, there is a punctured neighbourhood C of p, such that implies .

This corresponds to the regular topological definition of continuity, applied to the subspace topology on , and the restriction of f to .[citation needed]

Continuity

The function

is continuous at p if and only if f is defined at p and

If the function

is continuous in A if and only if, for every , f is defined at p and the limit of f(x) as x tends to p through A is f(p).[citation needed]

Every rational function P(x)/Q(x), where P and Q are polynomials, can be prolongated, in a unique way, to a function from to that is continuous in . In particular, this is the case of polynomial functions, which take the value at if they are not constant.[citation needed]

Also, if the tangent function tan is extended so that

then tan is continuous in but cannot be prolongated further to a function that is continuous in [citation needed]

Many elementary functions that are continuous in cannot be prolongated to functions that are continuous in This is the case, for example, of the exponential function and all trigonometric functions. For example, the sine function is continuous in but it cannot be made continuous at As seen above, the tangent function can be prolongated to a function that is continuous in but this function cannot be made continuous at [citation needed]

Many discontinuous functions that become continuous when the codomain is extended to remain discontinuous if the codomain is extended to the affinely extended real number system This is the case of the function On the other hand, some functions that are continuous in and discontinuous at become continuous if the ___domain is extended to This is the case of the arc tangent.[citation needed]

As a projective range

When the real projective line is considered in the context of the real projective plane, then the consequences of Desargues' theorem are implicit. In particular, the construction of the projective harmonic conjugate relation between points is part of the structure of the real projective line. For instance, given any pair of points, the point at infinity is the projective harmonic conjugate of their midpoint.[citation needed]

As projectivities preserve the harmonic relation, they form the automorphisms of the real projective line. The projectivities are described algebraically as homographies, since the real numbers form a ring, according to the general construction of a projective line over a ring. Collectively they form the group PGL(2,R).[citation needed]

The projectivities which are their own inverses are called involutions. A hyperbolic involution has two fixed points. Two of these correspond to elementary, arithmetic operations on the real projective line: negation and reciprocation. Indeed, 0 and ∞ are fixed under negation, while 1 and −1 are fixed under reciprocation.[citation needed]

Notes

- ^ An extension does however exist in which all the algebraic properties, when restricted to defined operations in , resolve to the standard rules: see Wheel theory.

- ^ If consistency of complementation is required, such that and for all (where the interval on either side is defined), all intervals excluding and may be naturally represented using this notation, with being interpreted as , and half-open intervals with equal endpoints, e.g. , remaining undefined.

- ^ For example, the ratio of intervals contains in both intervals, and since is undefined, the result of division of these intervals is undefined.

See also

- ^ a b c d e NBU, DDE (2019-11-05). PG MTM 201 B1. Directorate of Distance Education, University of North Bengal.

- ^ a b c d e f Weisstein, Eric W. "Projectively Extended Real Numbers". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2023-01-22.

- ^ Lee, Nam-Hoon (2020-04-28). Geometry: from Isometries to Special Relativity. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-030-42101-4.