Beowulf (c. between 700-1000 AD), is a traditional heroic epic poem written in Old English alliterative verse. At 3,182 lines — longer than any other Old English poem — it represents about 10% of the extant corpus of Old English poetry. The poem is untitled in the manuscript, but has been known as Beowulf since the early 19th century.

- This article describes Beowulf, the epic poem. For the character Beowulf, see Beowulf (hero). For other uses, see Beowulf (disambiguation).

Background and origins

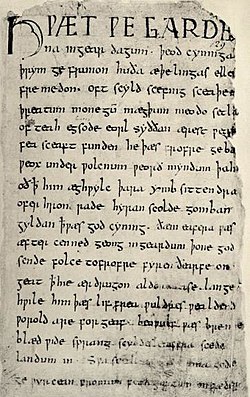

Beowulf is one of the oldest surviving epic poems in what is identifiable as an early form of the English language (the oldest surviving text in Old English is Caedmon's hymn of creation). The precise date of the manuscript is debated, but most estimates place it close to 1000. There is no general agreement on when the poem was originally composed. Some scholars argue that archaic forms of words that appear in the text suggest that the poem comes from the early 8th century, while others place it as late as the 10th century, near the time of the manuscript's copying. The poem appears in what is today called the Beowulf manuscript or Nowell Codex (British Library MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv), along with the shorter poem Judith and a handful of other works. The manuscript is the product of two different scribes, the second taking over roughly halfway through Beowulf.

In the poem, Beowulf, a hero of a Germanic tribe from southern Sweden called the Geats, travels to Denmark to help defeat a terrible monster. Why was a poem about Danish and Swedish kings and heroes preserved in England? The English people are descendants of Germanic tribes called the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Jutes and northern Saxon tribes came from what is now southern Denmark and northern Germany. Thus, Beowulf tells a story about the old days in their homeland.

The poem is a work of fiction, but it mentions a historic event, the raid by king Hygelac into Frisia, ca 516. Several of the personalities of Beowulf (e.g., Hrothgar, Hrothulf and Ohthere) and some of the events also appear in early Scandinavian sources, such as the Prose Edda, Gesta Danorum, the fornaldarsagas, etc. In these sources, especially the Hrólf Kraki tales deal with the same set of people in Denmark and Sweden (see Origins for Beowulf and Hrólf Kraki). The hero himself, appears to correspond to Bödvar Bjarki, the battle bear, and it is possible to read the name Beowulf as bee-wolf, a kenning for "bear" (due to their love of honey).

Consequently, many people and events depicted in the epic were probably real, dating from between 450 and 600 in Denmark and southern Sweden (Geats and Swedes). As far as Sweden is concerned this dating has been confirmed by archaeological excavations of the barrows indicated by Snorri Sturluson and by Swedish tradition as the graves of Eadgils and Ohthere in Uppland. Like the Finnsburg Fragment and several shorter surviving poems, Beowulf has consequently been used as a source of information about Scandinavian personalities such as Eadgils and Hygelac, and about continental Germanic personalities such as Offa, king of the continental Angles.

The traditions behind the poem would have arrived in England at a time when the Anglo-Saxons were still in close dynastic and personal contacts with their Germanic kinsmen in Scandinavia and northern Germany. It is the only substantial Old English poem to survive that addresses matters heroic rather than Christian.

The poem is known only from a single manuscript. The spellings in the surviving copy of the poem mix the West Saxon and Anglian dialects of Old English, though they are predominantly West Saxon, as are other Old English poems copied at the time. The earliest known owner is the 16th century scholar Lawrence Nowell, after whom the manuscript is known, though its official designation is Cotton Vitellius A.XV due to its inclusion in the catalog of Robert Bruce Cotton's holdings in the middle of the 17th century. It suffered irrepairable damage in the Cotton Library fire at the ominously-named Ashburnham House in 1731.

Icelandic scholar Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin made the first transcription of the manuscript in 1786 and published it in 1815, working under a historical research commission of the Danish government. Since that time, the manuscript has suffered additional decay, and the Thorkelin transcripts remain a prized secondary source for Beowulf scholars. Their accuracy has been called into question, however (e.g., by Chauncey Brewster Tinker in The Translations of Beowulf, a comprehensive survey of 19th century translations and editions of Beowulf), and the extent to which the manuscript was actually more readable in Thorkelin's time is unclear.

Themes & Story

The poem as we know it is a retelling of folktales from the Oral tradition for a Christian audience. It is often assumed that the work was written by a Christian monk, on the grounds that they were the only members of Anglo-Saxon society with access to writing materials. However, the example of King Alfred forces us to consider the possibility of lay authorship. In historical terms the poem's characters would have been pagans, but the narrator places events in a thoroughly Christian context, casting Grendel and Grendel's Mother as the kin of Cain, and placing Christian sentiments in his characters' mouths. [1]. Scholars disagree as to whether Beowulf's main thematic thrust is pagan or Christian in nature. However, it can be debated that since the only calligraphers were priests, it is possible that the story was, in fact, changed by a Christian who sought to apply a Christian character to his source.

Thus reflecting the above historical context, Beowulf depicts a Germanic warrior society, in which the relationship between the leader, or king, and his thanes is of paramount importance. This relationship is defined in terms of provision and service; the thanes defend the interest of the king in return for material provisions: weapons, armor, gold, silver, food, and drinks.

This society is strongly defined in terms of kinship; if a relative is killed it is the duty of surviving relatives to exact revenge upon his killer, either with his own life or with weregild, a reparational payment. In fact, the hero's very existence owes itself to this fact, as his father Ecgtheow was banished for having killed Heatholaf, a man from the prominent Wulfing clan. He sought refuge at the court of Hrothgar who graciously paid the weregild. Ecgtheow did not return home, but became one of the Geatish king Hrethel's housecarls and married his daughter, by whom he had Beowulf. The duty of avenging killed kinsmen became the undoing of king Hrethel, himself, because when his oldest son Herebeald was killed by his own brother Hæthcyn in a hunting accident, it was a death that could not be avenged. Hrethel died from the sorrow.

Moreover, this is a world governed by fate and destiny. The belief that fate controls him is a central factor in all of Beowulf's actions.

The story of Beowulf tells how King Hrothgar built a great hall called Heorot for his people. In it he and his warriors spend their time singing and celebrating, until Grendel, angered by their singing, attacks the hall and kills and eats many of Hrothgar's warriors. Hrothgar and his men, helpless against Grendel's attacks, have to abandon Heorot.

Beowulf, a young warrior, hears of Hrothgar's troubles and, with his king's permission, goes to help Hrothgar. Beowulf and his men spend the night in Heorot. After they fall asleep, Grendel enters the hall and attacks them, eating up one of Beowulf's men. Beowulf grabs Grendel's arm in a wrestling hold, and the two crash around in Heorot until it seems as though the hall will fall down with their fighting. Beowulf's men draw their swords and rush to his help, but there is a magic around Grendel that makes it impossible for swords to hurt him. Finally, Beowulf tears Grendel's arm from his body, and Grendel runs home to die.

The next night, after celebrating Grendel's death, Hrothgar and his men sleep in Heorot. But Grendel's Mother attacks the hall, killing Hrothgar's most trusted warrior in revenge for Grendel's death. Hrothgar and Beowulf and their men track Grendel's Mother to her lair under an eerie lake. Beowulf prepares himself for battle; he is presented a sword, Hrunting, by a warrior called Unferth. After stipulating a number of conditions upon his death to Hrothgar (including the taking in of his kinsmen, and the inheritance by Underth of Beowulf's estate) Beowulf dives into the lake. There, he is swiftly detected and grasped by Grendel's mother. She, unable to harm Beowulf through his armour, drags him to the bottom. There, in a cavern containing son's body and the remains of many men that the two have killed, Grendel's mother fights Beowulf. Grendel's mother at first prevails, after Beowulf, finding that the sword given him by Unferth cannot harm his foe, discards it in a fury. Again, he is saved from the effects of his opponent's attack by his armour and, grasping a mighty sword from Grendel's mother's armoury (which, the poem tells us, no other man could have hefted in battle) Beowulf beheads her. Travelling further into the lair, Beowulf discovers Grendel's corpse; he severs the head, and with it he returns to Heorot, where he is given many gifts by a even more grateful Hrothgar.

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, late in Beowulf's life, a man steals a golden cup from a dragon's lair. When the dragon sees that the cup has been stolen, it leaves its cave in a rage, burning up everything in sight. Beowulf and his warriors come to fight the dragon, but only one of the warriors, a young man named Wiglaf, stays to help Beowulf. Beowulf kills the dragon with Wiglaf's help but dies from the wounds he has received. The dragon's treasure is taken from its lair and buried with Beowulf's ashes. And with that the poem ends.

As the Norton Anthology of English Literature indicates, most scholars believe that Beowulf was written by a Christian poet [2]. Grendel and Grendel's Mother are described as descendants of Cain, and share similarities with antagonists in medieval Christian stories. Since, the Beowulf poet was also very knowledgeable about pagan beliefs, the descriptions of Grendel and Grendel's mother, for example, could owe as much to pagan beliefs about trolls as they do to Christian beliefs about demons. In addition, Beowulf's cremation at the end of the poem also refers to a pagan practice. Even though Beowulf was a pagan, the poem's Christian audience could admire his heroic deeds. Beowulf may thus be a product of the poet's knowledge of both Christian beliefs and the ancient history of his people. In combining them as he did, the Beowulf poet created a wonderful story.

Old English glossaries and modern English translations

Beowulf is the longest poem that has come down to us from Old English, the ancient form of modern English. The opening lines state:

"Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon."

In modern English, this reads:

"What! We have heard of the glory of the spear-Danes in the old days, of the people's kings, how the princes did deeds of valor."

Old English poetry such as Beowulf is very different from modern poetry. It was probably recited, for few people at that time were able to read. Instead of rhyme, poets typically used alliteration--a technique in which the first sound of each word in a line is the same, as in "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers." A line of Old English poetry usually has three words that alliterate. The meter, or rhythm, of the poetry works together with the alliteration: The stress in a line falls on the first syllables of the words that alliterate, as in the line "weo'x under wo'lcnum, weo'rðmyndum þah." (He grew under the sky, he prospered in his glory.)

Old English poets also used kennings, poetic ways of saying simple things. For example, a poet might call the sea the swan-road or the whale-road; a king might be called a ring-giver. There are many kennings in Beowulf. In fact, some scholars think the name Beowulf itself may be a kenning. It may mean "bee-wolf," a term for a bear, which attacks beehives the way a wolf attacks other animals.(Gay, David E., "Beowulf."The New Book of Knowledge. Scholastic Library Publishing, 2005<http://nbk.grolier.com> (October 17, 2005))

Fr. Klaeber's Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg has been the standard Old English text/glossary used by scholars since the 1920s. Two recent Old English text/glossaries include George Jack's 1997, Beowulf : A Student Edition. and Bruce Mitchell's 1998, Beowulf: An Edition with Relevant Shorter Texts.

The first translation, by Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin, was to Latin, in connection with the first publication of his transcription. Nicolai Grundtvig, greatly unsatisfied with this translation, made the first translation into a modern language — Danish — which was published in 1820. After Grundtvig's travels to England came the first English translation, by J. M. Kemble in 1837.

Since then there have been numerous translations of the poem in English. Irish poet Seamus Heaney and E. Talbot Donaldson have both published translations with W.W. Norton of New York. Other popular translations of the poem include those by Howell D. Chickering and Frederick Rebsamen.

J. R. R. Tolkien believed the translation by J. J. Earle was not accurate, and did not convey the meaning and symbolism of the storyline or the beauty of the prose of the poem. Chauncey Brewster Tinker was much more positive, however.

Form

The poem is in alliterative measure, in which the alliterative unit is the line and the metrical unit is the half-line.

Its poetic vocabulary included sets of metrical compounds that are varied according to alliterative needs. It also makes extensive use of elided metaphors.

The two halves of the poem are distinguished in many ways: youth then age; Denmark, then Geatland; the hall, then the barrow; public, then intimate; diverse, then focussed.

Here is a small sample including the first naming in the poem of Beowulf himself.

After each line is translation to modern English. A freely-available translation of the poem, now out of copyright, is that of Francis Gummere. It can be had at Project Gutenberg [3].

| Line | Original | Translation |

| oretmecgas æfter æþelum frægn: | ...asked the warriors of their lineage: | |

| "Hwanon ferigeað ge fætte scyldas, | "Whence do you carry ornate shields, | |

| græge syrcan ond grimhelmas, | Grey mail-shirts and masked helms, | |

| [335] | heresceafta heap? Ic eom Hroðgares | A multitude of spears? I am Hrothgar's |

| ar ond ombiht. Ne seah ic elþeodige | herald and officer. I have never seen, of foreigners, | |

| þus manige men modiglicran, | So many men, of braver bearing, | |

| Wen ic þæt ge for wlenco, nalles for wræcsiðum, | I know that out of daring, by no means in exile, | |

| ac for higeþrymmum Hroðgar sohton." | But for greatness of heart, you have sought Hrothgar." | |

| [340] | Him þa ellenrof andswarode, | To him, thus, bravely, it was answered, |

| wlanc Wedera leod, word æfter spræc, | By the proud Geatish chief, who these words thereafter spoke, | |

| heard under helme: "We synt Higelaces | Hard under helm: "We are Hygelac's | |

| beodgeneatas; Beowulf is min nama. | Table-companions. Beowulf is my name. | |

| Wille ic asecgan sunu Healfdenes, | I wish to declare to the son of Healfdene | |

| [345] | mærum þeodne, min ærende, | To the renowned prince, my mission, |

| aldre þinum, gif he us geunnan wile | To your lord, if he will grant us | |

| þæt we hine swa godne gretan moton." | that we might be allowed to address him, he who is so good." | |

| Wulfgar maþelode (þæt wæs Wendla leod; | Wulfgar Spoke – that was a Vendel chief; | |

| his modsefa manegum gecyðed, | His character was to many known | |

| [350] | wig ond wisdom): "Ic þæs wine Deniga, | His war-prowess and wisdom – "I, of him, friend of Danes, |

| frean Scildinga, frinan wille, | the Scyldings' lord, will ask, | |

| beaga bryttan, swa þu bena eart, | Of the ring bestower, as you request, | |

| þeoden mærne, ymb þinne sið, | Of that renowned prince, concerning your venture, | |

| ond þe þa ondsware ædre gecyðan | And will swiftly provide you the answer | |

| [355] | ðe me se goda agifan þenceð." | That the great one sees fit to give me." |

Influence upon contemporary works and pop culture

Literature

- The Catcher in the Rye: Holden Caulfield mentions Beowulf when explaining why English was the only subject he passed while attending Pencey Prep.

- Eaters of the Dead: The Beowulf story, in combination with the 10th century Arabic narrative of Aḩmad ibn Faḑlān, was used as the basis for this Michael Crichton novel.

- Grendel: The Beowulf story is retold from Grendel's point of view in this (1971) novel by John Gardner.

- The Heorot series of science-fiction novels, by Steven Barnes, Jerry Pournelle, and Larry Niven, is named after the stronghold of King Hrothgar and partly parallels Beowulf.

- Inheritance Trilogy: The King of the Dwarves in the these novels by Christopher Paolini is named Hrothgar, the same as the King of the Danes in Beowulf.

- The Lord of the Rings: Beowulf exercised an important influence on J. R. R. Tolkien, who wrote the landmark essay Beowulf: the monsters and the critics while a professor at Oxford University. Tolkien also translated the poem,which the Tolkien Society has recently decided to publish. Grendel and Grendel's mother were the inspiration for the Orcs in his Ring trilogy. Many parallels can also be drawn between Beowulf and The Hobbit.

Films

- Grendel, Grendel, Grendel (1981): an animated film based on John Gardner's novel and starring Peter Ustinov

- Animated Epics: Beowulf (1998): voiced by Joseph Fiennes

- The 13th Warrior (1999): This film, starring Antonio Banderas as Ibn Fadlan and Vladimir Kulich as Buliwyf (Beowulf), was based upon Crichton's novel mentioned above.

- Beowolf (1999): a science-fiction/fantasy film starring Christopher Lambert, loosely influenced by Beowulf

- Beowulf & Grendel (2005): an independent feature starring Gerard Butler

- Beowulf: Prince of the Geats (2006): a low-budget feature donating 100% of its sales and promotions to the American Cancer Society

- Beowulf (2007): a computer-animated feature directed by Robert Zemeckis

Additional film, television & music

- Star Trek Voyager: In the episode Heroes and Demons Ensign Harry Kim ran a holographic version of the Beowulf poem with himself as the central character.

- In the early 1980s, prog rock band Marillion released a song called Grendel based on aspects of the Beowolf narrative. In true prog rock traditions the song was in excess of 15 minutes and when played live involved lead singer Fish acting out a ritual 'slaughtering' of a member of the audience pulled out of the front row.

Games

- Beowulf: action adventure game based on the original story, coming for PC and console

- Castlevania: Aria of Sorrow: The magical sword Hrunting, which Beowulf used in his fight with Grendel's Mother, is featured in the GBA game.

- Devil May Cry 3: In this PlayStation 2 video game, Beowulf appears as a large, one-eyed demon. There were also a pair of gauntlets and leg guards imbued with light powers that were named Beowulf.

- Final Fantasy Tactics: In this video game, the main character's name is Ramza Beoulve, his last name possibly a mistranslation of Beowulf (in Japanese it would be the same katakana). The player also meets a knight named Beowulf who, ironically, is in love with a woman who has been transformed into a dragon. Beowulf and the player embark on a quest to restore her to her human form.

- Final Fantasy VIII: Grendel is featured as an enemy monster in this Playstation game.

Comics

- Speakeasy Comics: In April 2005 this series debuted a Beowulf monthly title featuring the character having survived into the modern era and now working alongside law enforcement in New York to handle superpowered beings.

- The renowned comics author Neil Gaiman has also depicted the tale of Beowulf in one of his comics.

- Beowulf by Reiner Knizia is a board game based on the poem. Published by Fantasy Flight Games, it is illustrated by famed Lord of the Rings artist John Howe.

References

Old English plus glossary

- Jack, George. Beowulf : A Student Edition. Oxford University Press: New York, 1997.

- Klaeber, Fr, and ed. Beowulf and the Fight at Finnsburg. Third ed. Boston: Heath, 1950.

- Mitchell, Bruce, et al. Beowulf: An Edition with Relevant Shorter Texts. Oxford, UK: Malden Ma., 1998.

Modern English translations

- Crossley-Holland, Kevin; Mitchell, Bruce. Beowulf: A New Translation. London: Macmillan, 1968.

- Heaney, Seamus. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001.

- --"Introduction" in Crossley-Holland, Kevin (tr.) Beowulf. London: Folio, 1973.

- Swanton, Michael (ed.). Beowulf (Manchester Medieval Studies). Manchester: University, 1997.

- Tinker, Chauncey Brewster. The translations of Beowulf; a critical bibliography. New York: Holt, 1903. (Modern reprint with new introduction, Hamden: Archon Books, 1974).

External links

- Beowulf read aloud in Old English

- Translations of Beowulf at Project Gutenberg:

- Beowulf in Cyberspace

- Ringler, Dick. Beowulf: A New Translation For Oral Delivery, May 2005. Searchable text with full audio available, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries.

- Several different Modern English translations

- Summary of the story

- Beowulf: Recognizing the Past an article from Shadowed Realm - Your Guide to Medieval History

- Christianity in Beowulf an article from Shadowed Realm - Your Guide to Medieval History

- James Grout: Beowulf, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Beowulf: The Movie(s). A Comprehensive Look at the (Brief) List of Cinematic Adaptations of the English Language's Most Enduring Epic Poem an article from Film as Art: Danél Griffin's Guide to Cinema

- Additional information about the Ashburnham House fire