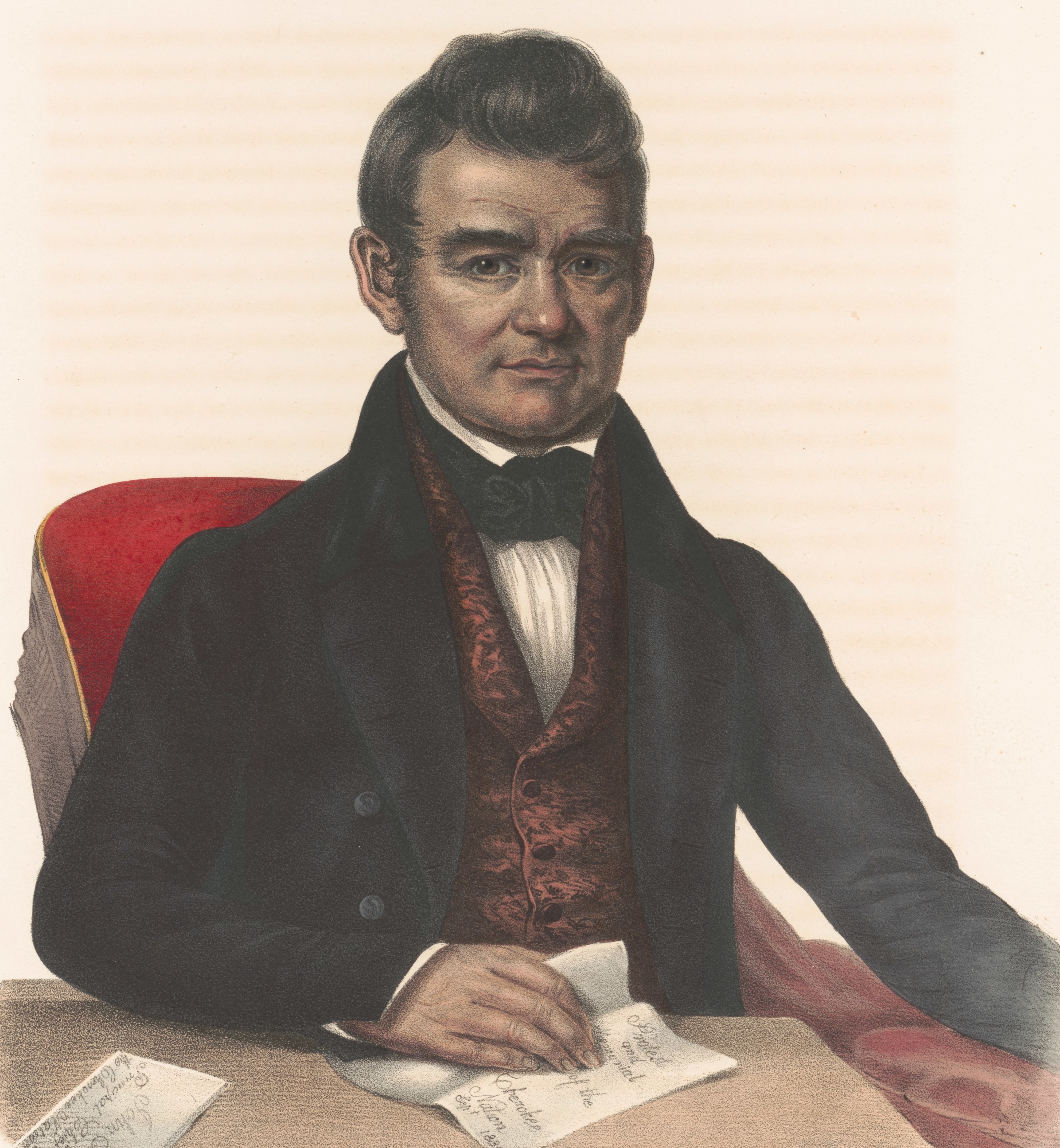

John Ross (October 3, 1790 - August 1, 1866), also known as Kooweskoowe - "the egret", was a leader of the Cherokee Native American tribe.

John Ross |

|---|

Introduction

Between 1819 and 1866, the Cherokees became a nation state, lost their ancestral land, endured removal to the Indian Territory, and suffered destructive civil war. Throughout these tumultuous years, the dominant political figure in the Cherokee Nation was John Ross, whose leadership spanned the entire period. By "blood", Ross was seven-eigths Scotch-Irish, educated by Europeans, a poor speaker of the Cherokee language, and one of the wealthiest men of the nation. Ironically, in term of heritage, education, status, and economic pursuits, Ross more closely resembled his political foes President Andrew Jackson or Governor George R. Glimer of Georgia than he did the majority of the Cherokee Nation. In Washington social circles it was remarked that in "manners and deportment...[Ross had] in no respect differed from those of well-bred country gentleman."

The Cherokee Moses

Given Ross's background it would seem unlikely that Ross would involve himself in Cherokee affairs, and in so doing emerge, as the dominant political figure of the Cherokee Nation. However, despite a vocal minority of Cherokees and a generation of political leaders in Washington who considered Ross to be dictatorial, greedy, and an "aristocratic leader [who] sought to defraud" the Cherokee Nation, the majority of Cherokees ardently supported Ross and elected him pricinpal chief in every election from 1828 through 1860. Ross also had supporters in Washington, including Thomas L. McKenney, a commissioner of Indian affairs (1824 - 1830) who described Ross as the father of the Cherokee Nation, a Mosee who "lead...his people in their exodus from the land of their nativity to a new country, and from the savage state to that of civilization."

Childhood

Ross was born near Lookout Mountain,Alabama, to Mollie and Daniel Ross. Ross's geneology begins with William Shorey, a Scottish interpreter, and his "fullblood" wife Ghigooie, a member of the bird clan. In 1769, their daughter, Anna, married John McDonald, a Scottish trader at Fort Loundoun, in Tennessee. In 1786, their daughter, Mollie, married Daniel Ross, a Scotsman who had gone to live among the Cherokee during the American Revolution.

Ross's childhood, spent in the area of Lookout Mountain, was immersed in Cherokee society, where he encountered the fullblood Cherokee who frequented his father's trading company. As a child, Ross was allowed to participate in Cherokee events such as the Green Corn Festival. Despite his father's willingness to allow his son to partake in some Cherokee custome, the elder Ross was determined that his sone receive a rigorous education. After receiving an elementary education at home, Ross studied with the Reverend Gideon Blackburn and finished his education at an academy in South West Point, Tenneesee.

Business Activities

At the age of twenty, after having completed his education, he was appointed as Indian agent to the western Cherokee and sent to Arkansas. He served as an adjutant in a Cherokee regiment during the War of 1812 and participated in fighting at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the British-allied Creek tribe.

Ross then began a series of business venture, but derived the majority of his wealth from an extensive plantation worked by slaves. (The Cherokee Nation jointly owned all land, however, improvements on the land could be sold or willed.) In 1816 he founded Ross's Landing (which was renamed Chattanooga after his departure for the Trail of Tears). In addition, Ross established a trading firm and warehouse. In total, Ross earned upwards on one-thousand dollars a year. In 1827, Ross moved to Coosa to be closer to New Echota, the Cherokee capital, and the other leading figures of the nation. In Coosa, Ross established another ferry and had twenty slaves cultivating 170 acres. By December 1836, Ross's property was apprasied at $23,665.75, which made him one of the five wealthiest men in the Cherokee Nation.

Rise to National Leadership

Political Apprenticeship

The years 1812 to 1827, were a period of political apprenticeship for Ross. Before he would lead the Cherokee people he had to learn about negotiations with the United States and how to lead a nation. After 1814, Ross's political career, as a Cherokee legislator and diplomat, progressed with the support of individuals like Principal Chief Pathkiller, Associate Chief Charles Hicks, and Major Ridge, an elder statement of the Cherokee Nation. In 1813, as relations with the United States became more complex, older, uneducated Chiefs like Pathkiller could not effectively defend Cherokee interests. The ascendancy of Ross represented an acknowledgement by the Cherokee that an educated, English-speaking leadership was of national importance, and both Pathkiller and Hicks saw Ross as the future leader of the Cherokee Nation and trained him for this work. Ross served as clerk to Pathkiller and Hicks; working in this capacity on all financial and political matters of the nation. Equally important in the education of the future leader of the Cherokees was instruction in the traditions of the Cherokee Nation.

In 1816, Ross was named by the National Council to his first delegation to Washington. The delegation of 1816 was directed to resolve the sensitive issues of national boundaries, landownership, and white intrusions on Cherokee land. Of the delegates, only Ross was fluent in English, making him the central figure in the negotiations. Ross's first political position came in November 1817 with the formation of the National Council; a thirteen member body elected for two year terms. The National Council was created to consolidate Cherokee political authority after General Jackson made two treaties with small cliques of Cherokees representing minority factions. Membership in the National Council placed Ross among the ruling elite in the upper echolons of the Cherokee leadership.

Assumption of Leadership

In November 1818, on the eve of the General Council meeting with the Cherokee agent Joseph McMinn, Ross was elevated to the presidency of the National Committee; a position he held through 1827. The Council selected Ross for this position because they perceived him to have the diplomatic skill necessary to rebuff requests to cede Cherokee lands. In this tak, Ross did not disappoint the Council. McMinn offered two-hundred thousand dollars for removal of the Cherokees beyond the Mississippi, which Ross refused.

In 1819, Ross was again sent to Washington; unlike 1816, however, Ross was now assuming a larger role in the leadership. The purpose of the delegation was to clarify the provisions of the Treaty of 1817. The delegation had to negotiate the limits of the ceded land and hope to clarify the Cherokee's right to the remaining land. John C. Calhoun, the secretary of war, pressed Ross to cede large tracts of land in Tennessee and Georgia. Such press would continue and intensify. In October 1822, Calhoun requrested that the Cherokee relinquish their land claimed by Georgia, in fulfillment of the United State's obligation under the Compromise of 1802. Before responding to Calhoun's proposition, Ross first ascertained the sentiment of the Cherokee people, which he found to be unanimously opposed to cession of land.

In January 1824, Ross travled yet again to Washington to defend the Cherokees' possession of their land, where Calhoun offered two solutions to the Cherokee delegation: either relinquish title to their lands and remove west or accept denationalization and become citizens of the United States. Rather than accept Calhoun's ultimatum, Ross made a bold departure from previous negotiations by continuing to aggressively press their complaints, and on April 15, 1824, Ross took the dramatic step of petitioning Congress. This fundamentally altered the traditional relationship between an Indian nation and whites dating back to colonial times.

Never before had an Indian nation petitioned Congress with grievances, and in Ross' correspondences the petitions of submissive Indians were replaced by assertive defenders, albe to argue, as well as whites, subtle points about legal responsibilities. This change was apparent to individuals in Washington, including future president John Quincy Adams, who wrote that "there was less Indian oratory, and more of the common style of white discourse, than in the same chief' speech on their first introduction." Adams specifically noted Ross' work as "the writter of the delegation" and remarked that "they [had] sustained a written controversy against the Georgia delegation with greate advantage." Indeed the Georgia delegation acknowledged Ross' skill in an editorial in The Georgia Journal which charged that the Cherokee delegation's letters were fraudulent because they were too refined to have been written or dictated by an Indian.

Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation

In time, Ross became assistant chief of the eastern Cherokee and in January 1827, with the death of Pathkiller, the Cherokee's principal chief, Ross became principal chief protem. During the same period that Ross was negotiating in Washington on behalf of the Cherokee, the Cherokee Council began to pass a series of laws creating a bicameral national governement and in 1822 created the Cheorkee Supreme Court, capping the creation of a three branch government. In May 1827, Ross was elected to the twenty-four member constitutional committee, which drafted a constitution calling for a principal chief, a council of the principal chief, and a National Committee, which together would form the General Council of the Cherokee Nation. Although the constitution was ratified in October 1827, it did not take effect until October 1828, at which point, Ross was elected principal chief, a position he would hold until his death.

When Ross and the Cherokee delation failed to in their efforts to protect Cherokee lands through negotiation with the executive branch and through petitions with Congress, Ross took the radical step of defending Cherokee rights through the U.S. courts. In June 1830, at the urging of Sentators Daniel Webster and Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen, the Cheorkee delegation selected William Wirt, attorney general in the Monroe and Adams administrations, to defend Chereokee rights before the U.S. Supreme Court.

During his tenure as chief he opposed displacement of the tribe from its native lands, a policy of the United States government known as Indian Removal. However, Ross's political rival Major Ridge signed an unauthorized removal treaty with the U.S. in 1836. Ross unsuccessfully lobbied against enforcement of the treaty, but those Cherokees who did not emigrate to the "Indian Territory" by 1838 were forced to do so by General Winfield Scott, an episode that came to be known as the "Trail of Tears." Accepting defeat, Ross convinced General Scott to have supervision of much of the removal process turned over to Ross.

The Trail of Tears and Beyond

On the trail of tears Ross lost his wife, Quatie, a fullblooded Cherokee woman, of whom little is known.

In the Indian Territory, Ross helped draft a constitution for the entire Cherokee nation in 1839, and was chosen as chief of the nation.

Civil War Period

When the Civil War began to heat up the Confederate government looked to the American Indians as both a source of foodstuffs and men. The Confederates sent Albert Pike on a mission to sign treaties with the Native Americans in Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and John Ross received Pike. Ross gave Pike a cold reception and rejected his offers. Pike would return to the Cherokees after signing a treaty with the Creeks to find a different situation.

Since the Treaty of New Echota, the Cherokee nation was deeply divided between the party that signed the treaty and the holdouts. The Party who signed the treaty, also called the Ridge Party, had slaves, land, livestock, spoke English as their primary language, and attempted to become "American". The holdouts consisted of traditionalists who still spoke their native tongue as their primary language and rejected European ways of life. The recent removal of the Cherokee (the Trail of Tears) also added to these tensions.

When Pike returned in August of 1861, a party of Southern supporting Cherokees of the Ridge Party had formed their own regiment led by Stand Watie. Ross saw no other option but to sign the treaty with the Confederates. Ross' followers (called the Pins) formed their own regiment led by John Drew. When a contingent of Creeks who did not want to join the Confederacy attempted to flee to Union lines in Kansas, the Confederate forces consisting of Native infantry and Texas Cavalry pursued and pinned them down at Bird Creek.

During the battle John Drew's forces broke ranks and joined the Creeks and the battle ended in a draw. As the Creeks made their way to Kansas Watie's forces again hunted them down and inflicted heavy losses. By 1862, the Union forces had control of Southern Missouri and were able to force the Confederates into a battle at Pea Ridge. After an immense struggle, the Union was able to secure victory but Watie's forces were able to retreat. Reports of Natives on the side of the Confederates were on the front page of the newspapers in the North and increased American fears of the Natives. With this defeat, the Cherokee nation was abandoned by the Confederacy. Insulted, Ross surrendered to the Union army and invited them into Cherokee lands.

While in prison, the situation in Cherokee lands grew dire. The Union army, constantly berated by their commander, mutinied and went north to Kansas leaving Cherokee lands without a government. In the resulting anarchy, old feuds were settled with gunfire and death. The Union restored order in 1863 when William Philips led a multi-ethnic army into Cherokee lands.

Ross stayed in Washington from October 1862 through July 1865 working to defend Cheorkee treaty rights and insure the welfare of the nation for the duratin of the war. The government-in-exile received grievances and updates from citizens who remained in the nation, while Ross, who gained access to members of Congress and the Executive, lobbied to aid the Cherokee as well as the other western nations.

In his final annual message on October 1865, Ross assessed the Cherokee experience during the civil war and his performance as chief. The Cherokee could "have the proud satisfaction of knowing that we honestly strove to preserve the peace within our borders, but when this could not be done,...borne a gallant part in the defense...of the cause which has been crowned with such signal success."