Utente:Mikialba/Sandbox2

Questa Sandbox funge da "brutta copia" dei miei futuri articoli.

Questa Sandbox funge da "brutta copia" dei miei futuri articoli.

Il polmone è l'organo essenziale per la respirazione nei vertebrati. La sua principale funzione è di trasportare ossigeno dall'atmosfera al sangue e di espellere anidride carbonica dal sangue all'atmosfera. Questo scambio di gas è compiuto in un mosaico di cellule specializzate che formano delle piccole sacche d'aria chiamate alveoli. I polmoni hanno anche delle funzioni non respiratorie.

I termini medici che si riferiscono al polmone molto spesso cominciano con il prefisso -pulmo, dal Latino pulmonarius e dal Greco pleumon.

Funzione respiratoria

L'energia prodotta dalla respirazione cellulare richiede ossigeno e produce anidride carbonica. Nei piccoli organismi, come i batteri, questo processo di scambio di gas è svolto interamente dalla diffusione semplice. Nei grandi organismi, questo none è possibile; solo una bassa percentuale di cellule permettono di far entrare l'ossigeno tramite diffusione. La respirazione negli organismi multicellulari è possibile grazie ad un efficiente sistema circolatorio, il quale trasporta i gas anche nelle parti più piccole e profonde del corpo, e al sistema respiratorio, che coglie l'ossigeno dall'atmosfera e lo diffonde nel corpo, da dove viene distribuito rapidamente in tutto l'apparato circolatorio.

Nei vertebrati, la respirazione avviene in una serie di passi. L'aria passa per le vie respiratorie - nei rettili, negli uccelli e nei mammiferi consistono nel naso; la faringe; la laringe; la trachea; i bronchi e i bronchioli; infine vi sono gli ultimi branchi dell'albero della respirazione. The lungs of mammals are a rich lattice of alveoli, which provide an enormous surface area for gas exchange. A network of fine capillaries allows transport of blood over the surface of alveoli. Oxygen from the air inside the alveoli diffuses into the bloodstream, and carbon dioxide diffuses from the blood to the alveoli, both across thin alveolar membranes. The drawing and expulsion of air is driven by muscular action; in early tetrapods, air was driven into the lungs by the pharyngeal muscles, whereas in reptiles, birds and mammals a more complicated musculoskeletal system is used. In the mammal, a large muscle, the diaphragm (in addition to the internal intercostal muscles), drive ventilation by periodically altering the intra-thoracic volume and pressure; by increasing volume and thus decreasing pressure, air flows into the airways down a pressure gradient, and by reducing volume and increasing pressure, the reverse occurs. During normal breathing, expiration is passive and no muscles are contracted (the diaphragm relaxes). Another name for this inspiration and expulsion of air is ventilation.

Nonrespiratory functions

In addition to respiratory functions such as gas exchange and regulation of hydrogen ion concentration, the lungs also:

- influence the concentration of biologically active substances and drugs used in medicine in arterial blood

- filter out small blood clots formed in veins

- serve as a physical layer of soft, shock-absorbent protection for the heart, which the lungs flank and nearly enclose.

Mammalian lungs

The lungs of mammals have a spongy texture and are honeycombed with epithelium having a much larger surface area in total than the outer surface area of the lung itself. The lungs of humans are typical of this type of lung. The environment of the lung is very moist, which makes it a hospitable environment for bacteria. Many respiratory illnesses are the result of bacterial or viral infection of the lungs.

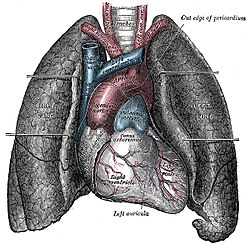

Air enters through the oral and nasal cavities; it flows through the larynx and into the trachea, which branches out into bronchi. In humans, it is the two main bronchi (produced by the bifurcation of the trachea) that enter the roots of the lungs. The bronchi continue to divide within the lung, and after multiple generations of divisions, give rise to bronchioles. Eventually the bronchial tree ends in alveolar sacs, composed of alveoli. Alveoli are essentially tiny sacs in close contact with blood filled capillaries. Here oxygen from the air diffuses into the blood, where it is carried by hemoglobin, and carried via pulmonary veins towards the heart.

Deoxygenated blood from the heart travels via the pulmonary artery to the lungs for oxidation.

Avian lungs

Many sources state that it takes two complete breathing cycles for air to pass entirely through a bird's respiratory system. This is based on the idea that the bird's lungs store air received from the posterior air sacs in the 'first' exhalation until they can deliver this air to the posterior air sacs in the 'second' inhalation.

Avian lungs do not have alveoli, as mammalian lungs do, but instead contain millions of tiny passages known as parabronchi, connected at either ends by the dorsobronchi and ventrobronchi. Air flows through the honeycombed walls of the parabronchi and into air capillaries, where oxygen and carbon dioxide are traded with cross-flowing blood capillaries by diffusion, a process of crosscurrent exchange.

This complex system of air sacs ensures that the airflow through the avian lung is always travelling in the same direction - posterior to anterior. This is in contrast to the mammalian system, in which the direction of airflow in the lung is tidal, reversing between inhalation and exhalation. By utilizing a unidirectional flow of air, avian lungs are able to extract a greater concentration of oxygen from inhaled air. Birds are thus equipped to fly at altitudes at which mammals would succumb to hypoxia.

Reptilian lungs

Reptilian lungs are typically ventilated by a combination of expansion and contraction of the ribs via axial muscles and buccal pumping. Crocodilians also rely on the hepatic piston method, in which the liver is pulled back by a muscle anchored to the pubic bone (part of the pelvis), which in turn pulls the bottom of the lungs backward, expanding them.

Amphibian lungs

The lungs of most frogs and other amphibians are simple balloon-like structures, with gas exchange limited to the outer surface area of the lung. This is not a very efficient arrangement, but amphibians have low metabolic demands and also frequently supplement their oxygen supply by diffusion across the moist outer skin of their bodies. Unlike mammals, which use a breathing system driven by negative pressure, amphibians employ positive pressure. Note that the majority of salamander species are lungless salamanders and conduct respiration through their skin and the tissues lining their mouth.

Invertebrate lungs

Some invertebrates have "lungs" that serve a similar respiratory purpose but are not evolutionarily related to vertebrate lungs. Some arachnids have structures called "book lungs" used for atmospheric gas exchange. The Coconut crab uses structures called branchiostegal lungs to breathe air and indeed will drown in water, hence it breathes on land and holds its breath underwater. The Pulmonata are an order of snails and slugs that have developed "lungs".

Origins

The first lungs, simple sacs that allowed the organism to gulp air under oxygen-poor conditions, evolved into the lungs of today's terrestrial vertebrates and into the gas bladders of today's fish. The lungs of vertebrates are homologous to the gas bladders of fish (but not to their gills). The evolutionary origin of both are thought to be outpocketings of the upper intestines. This is reflected by the fact that the lungs of a fetus also develop from an outpocketing of the upper intestines and in the case of gas bladders, this connection to the gut continues to exist as the pneumatic duct in more "primitive" teleosts, and is lost in the higher orders. (This is an instance of correlation between ontogeny and phylogeny.) There are no animals which have both lungs and a gas bladder.