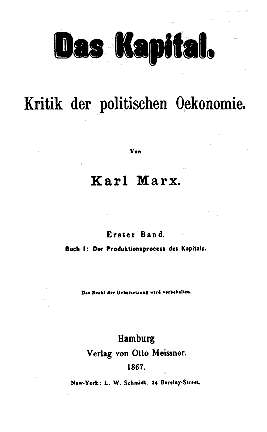

Das Kapital ("Capital") is a very large treatise of political economy written by Karl Marx in German in 1867. The book is a critical analysis of capitalism, its economic practices and the theories which economists made about it. As noted by S. S. Prawer in "Karl Marx and World Literature" (1978), it has not only scientific but also important literary merits.

Marx bases his work on that of the classical economists like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill and even Benjamin Franklin. However, he reworks these authors' ideas critically and carefully, so his book is a critical and innovative synthesis that does not follow the lead of any one thinker. It also reflects the dialectical methodology applied by G.W.F. Hegel in his books The Science of Logic and The Phenomenology of Mind, and the influence of French socialists such as Charles Fourier, Comte de Saint-Simon, and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

Marx said himself that his aim was "to bring a science [i.e. political economy] by criticism to the point where it can be dialectically represented", and in this way to "reveal the law of motion of modern society". By showing how capitalist development was the precursor of a new, socialist mode of production, he aimed to provide a scientific foundation for the modern labour movement. In preparation for his book, he studied the economic literature available in his time for a period of twelve years, mainly in the British Museum in London.

The central injustice of capitalism, according to Marx, was in the exploitation and alienation of labour, a condition which a later Marxist thinker, Harry Braverman, in his work Labour and Monopoly Capital: the degradation of work in the 20th Century, called "the degradation of labour". The ultimate source of the new profits and value-added was that employers paid workers the market value of their labour-capacity, but the value of the commodities workers produced exceeded that market value. Employers were entitled to appropriate the new output value because of their ownership of the productive capital assets. By producing output as capital for the employers, the workers constantly reproduced the condition of capitalism by their labour.

However, though Marx is very concerned with the social aspects of commerce, his book is not an ethical treatise, but an (unfinished) attempt to explain the objective "laws of motion" of the capitalist system as a whole, its origins and future. He aims to reveal the causes and dynamics of the accumulation of capital, the growth of wage labour, the transformation of the workplace, the concentration of capital, competition, the banking and credit system, the tendency of the rate of profit to decline, land-rents and many other things.

Marx viewed the commodity as the "cell-form" or building unit of capitalist society — it is an object useful to somebody else, but with a trading value for the owner. Because commercial transactions implied no particular morality beyond that required to settle transactions, the growth of markets caused the economic sphere and the moral-legal sphere to become separated in society: subjective moral value becomes separated from objective economic value. Political economy, which was originally thought of as a "moral science" concerned with the just distribution of wealth, or as a "political arithmetick" for tax collection, gave way to the separate disciplines of economic science, law and ethics.

Marx believed the political economists could study the scientific laws of capitalism in an "objective" way, because the expansion of markets had in reality objectified most economic relations: the cash nexus stripped away all previous illusions. Marx also says that he viewed "the economic formation of society as a process of natural history". The growth of commerce happened as a process which no individuals could control or direct, creating an enormously complex web of social interconnections globally. Thus a "society" was formed "economically" before people actually began to consciously master the enormous productive capacity and interconnections they had created, in order to put it collectively to the best use.

Marx published the first volume of Das Kapital in 1867, but he died before he could finish the second and third ones which he had already drafted; these were edited by his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels and published in 1885 and 1894; the fourth volume, called Theories of Surplus-Value, was first edited and published by Karl Kautsky in 1905-1910. Other preparatory manuscripts were published only decades later.

See also

- capital

- history of theory of capitalism

- surplus value

- surplus labour

- Labor theory of value

- value added

- law of value

- valorisation

- profit

- law of value

- capital accumulation

- law of accumulation

- accumulation by dispossession

- primitive accumulation of capital

- commodity fetishism

- return on capital

- cost of capital

- relations of production

- culture of capitalism

Online editions

External links

- Annotations, Explanations and Clarifications to Capital. Will help with understanding the early concepts.

- Wage Labour and Capital. An earlier document that deals with many of the ideas later expanded in Das Kapital.

- Engels's Synopsis of Das Kapital (PDF document)