Early history to 1599

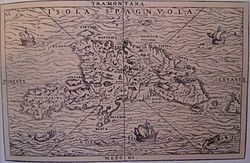

The island of Hispaniola, of which the Dominican Republic forms the eastern two-thirds and Haiti the remainder, was originally occupied by Taínos, an Arawak-speaking people who called the island Quisqueya (or Kiskeya). The island was divided by a system of five major Cacicazgos (chiefdoms) - Marien, Maguana, Higuey, Magua and Xaragua (Also written as Jaragua). These chiefdoms were further subdivided into subchiefdoms. The Cacicazgos were supported by a tributary arrangement, consisting of food provided by the Taino. Among the remaining cultural inheritances from the Taino-era are cave paintings scattered throughout the country and words from the Arawak language, including "hurricane" (hurrakan) and "tobacco" (tabakko).

The arrival of the Guamikena (the covered ones)

On December 5, 1492, the Europeans arrived. Believing that these horizon were in someway supernatural, the Taínos welcomed the Europeans with all the honors available to them. This was a totally different society from the one the Europeans came from. One of the things that piqued the curiosity was the amount of clothing worn by the Europeans. Therefore they came to call them "guamikena" (the covered ones). Guacanagarix, the chief who hosted Christopher Columbus and his men, treated them kindly and provided him with everything they desired. Yet the Taínos' allegedly "egalitarian" system clashed with the Europeans' feudalist system, with more rigid class structures. This led the Europeans to believe the Taínos to be either weak or misleading, and they began to treat the tribes with more violence. Columbus tried to temper this when he and his men departed from Quisqueya and they left on a good note. Columbus had cemented a firm alliance with Guacanagarix, who was a powerful chief on the island. After the shipwrecking of the Santa Maria, he decided to establish a small fort with a garrison of men that could help him lay claim to this possession. The fort was called La Navidad, since the events of the shipwrecking and the founding of the fort occurred on Christmas day. The garrison, in spite of all the wealth and beauty on the island, was wracked by divisions within and the men took sides, that evolved into conflict amongst these first Europeans. The more rapacious ones began to terrorize the Taíno, Ciguayo and Macorix tribesmen up to the point of trying to take their women.

Viewed as weak by the Spaniards and even some of his own people, Guacanagarix tried to come to an accommodation with the Spaniards, who saw his appeasement as the actions of someone who submitted. They treated him with contempt and even took some of his wives too. The powerful cacique of the maguana, Caonabo, could brook no further affronts and attacked the Europeans, destroying La Navidad. Guacanagarix was dismayed by this turn of events but did not try too hard to aid these guamikena, probably hoping that the troublesome outsiders would never return. However, they did return.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus came back to the island on his second voyage and founded the first Spanish colony in the New World, the city of Isabella. An estimated 400,000 Tainos living on the island were soon enslaved to work in gold mines. As a consequence of oppression, forced labor, hunger, disease, and mass killings, it is estimated that by 1508 that number had been reduced to around 60,000. By 1535, only a few dozen were still alive.[1]

During this period, the Spanish leadership changed hands several times. When Columbus departed on another exploration, Francisco de Bobadilla became governor. Settlers' charges against Columbus of mismanagement added to the tumultuous political situation. In 1502, Nicolás de Ovando replaced de Bobadilla as governor, with an ambitious plan to expand Spanish influence in the region. It was he who dealt most brutally with the Taínos.

Although Caonabo had previously been captured, his queen, Anacoana, had carried on his rule. Because of her highly respected position among the Taíno chiefs, de Ovando requested that she welcome him as the new governor by hosting a feast. She agreed, and invited eighty other chieftans to the celebration. Instead of attending, de Ovando ordered his soldiers to burn down her palace with everyone inside. Most of them perished. Although a few managed to escape, they were captured and tortured. Anacoana was given a mock trial, then hung. De Ovando's ploy to eliminate Taíno chiefs was so successful, he used similar methods on the other side of the island. Stripping the Taínos of their leaders made rebellion far more difficult.

One rebel, however, successfully fought back. Enriquillo, leading a group of those who had fled to the mountains, attacked the Spanish repeatedly for fourteen years. Finally, the Spanish offered him a peace treaty. In addition, they gave Enriquillo and his followers their own city in 1534. The city did not last long, however; several years after its establishment, a slave rebellion burned it to the ground, killing anyone who stayed behind.

African enslavement

In 1501, the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand and Isebella, first granted permission to the colonists of the Caribbean to import African slaves, which began arriving to the island in 1503. These African importees arrived with a rich and ancient culture that has had considerable influence on the racial, political and cultural character of the modern Dominican Republic. In 1510, the first sizable shipment, consisting of 250 Black Ladinos, arrived in Hispaniola from Spain. Eight years later African-born slaves arrived in the West Indies. Sugar cane was introduced to Hispaniola from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established in 1516.[2] The need for a labor force to meet the growing demands of sugar cane cultivation led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves over the following two decades.

The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Santo Domingo during 1522, when enslaved Muslims of the Wolof nation led an uprising in the sugar plantation of admiral Don Diego Colon, son of Christopher Columbus. Many of these insurgents managed to escape to the mountains where they formed independent maroon communities.

1600-1929

With the conquest of the American mainland, Hispaniola quickly declined. Most of the islands’ Spanish colonists left for the silver-mines if Mexico and Peru, while new immigrants from Spain largely bypassed the island for the greater wealth to be found in the lands to the west. Santo Domingo was bypassed as the designated stopping point for the merchant flotas which had a royal monopoly on commerce in favor of Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream. Agriculture dwindled, new imports of slaves ceased and many of the surviving slaves fled into the mountains, becoming cimarrones, and the island became a haven for English, French and Dutch pirates who overran the Caribbean.

In the next century, livestock, and increasingly, contraband trade became major sources of livelihood for the island dwellers. Spain, unhappy that Santo Domingo was facilitating trade between its other colonies and other European powers, attacked vast parts of the colony's northern and western regions in the early 17th century.[3] As a result of this disastrous action, known as the devastaciones more than half the colonists who were resettled died of starvation or disease. This helped pave the way for French settlers to occupy the depopulated western end of the island, which Spain ceded to France in 1697, and which, in 1804, became the Republic of Haiti. Throughout the seventeenth-century, colonial Santo Domingo's economy remained in collapse, and colonists, free blacks and slaves, leading to a weaking of the racial hierarchy and aiding mulatización.

In the end of the 18th century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands, and the beginning of tobacco agriculture in the Cibao valley, enabling renewed importation of slaves. However, Santo Domingo remained neglected outpost of Spain's colonial empire. The black Jacobin'Toussaint L'Ouverture conquered Santo Domingo on behalf of the French Republic in 1801, proclaiming the abolition of slavery. Shortly afterwards, Napoleon dispatched an army to subdue the colony. Even after their defeat by the Haitians, a small French garisson remained in the Spanish colony, where slavery was reestablished. In 1805, after crowning himself Emperor, Jean-Jacques Dessalines invaded the eastern part of the island, reaching Santo Domingo before retreating in the face of a French naval squadron. In their advance and retreat through the Cibao, the Haitians sacked the major towns, including Santiago de los Caballeros, slaughtering most of their residents. This invasion helped lay the foundation for two centuries of animosity between the two countries.

The French held on in the eastern part of the island, until defeated by the Spanish inhabitants at the Battle of Palo Hincado on November 7, 1808 and the final capitulation of the besieged Santo Domingo on July 9, 1809, with help from the Royal Navy. The Spanish authorities showed little interest in their restored colony, and the following period is recalled as La España Boba – 'The Era of Foolish Spain'. The great ranching families such as the Santanas came to be the leaders in the south east, the law of the "machete" ruled for a time. In 1821, the Spanish settlers declared an independent state, but Haitian forces occupied the whole island just nine weeks later and held it for 22 years.

Haitian occupation

The twenty-two-year Haitian occupation that followed is recalled by Dominicans as a period of brutal military rule, though the reality is more complex. It led to large-scale land expropriations and failed efforts to force production of export crops, impose military services, restrict the use of the Spanish language, and eliminate traditional customs such as cockfighting. It reinforced Dominican's perceptions of themselves as different from Haitians in "language, race, religion and domestic customs."[4] Yet, this was also a period that definitively ended slavery as an institution in the eastern part of the island.

Independence from Haiti to War of Restoration

On February 27, 1844, independence was declared from the Haitians. This was the culmination of a movement led by Juan Pablo Duarte, then in exile, the hero of Dominican independence. The military forces that drove the occupiers out were led by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle rancher who commanded a private army of peasants who worked on his estates.

The Dominican Republic's first constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844. It adopted a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by Article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana on the constitutional assembly by force, which gave him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence was over. These privileges not only served him to win the war, but also allowed him to persecute, execute and drive into exile his political opponents, among which Duarte was the most important. In 1848 he appointed a Azua mahogany exporter named Buenaventura Báez as President, but in 1853 forcibly deposed and exiled him. Three years later, after repulsing the last Haitian invasion, he negotiated a treaty leasing a portion of Samaná Peninsula to a U.S. company; popular opposition forced him to abdicate, enabling Báez to seize power. With the treasury depleted, Baez printed eighteen million uninsured pesos, purchasing the 1857 tobacco crop with this currency and exporting it for hard cash at immense profit to himself and his followers. The Cibao Valley tobacco planters, who were ruined when inflation ensued, revolted, recalling Santana from exile. After a year of civil war, Santana seized Santo Domingo and installed himself as President.

In 1861, during one of his presidencies, Santana restored the Dominican Republic to Spain. This move was widely rejected and on August 16, 1863, a national war of "restoration" began in Santiago. Although Spanish troops reoccupied the town, the rebels fled to the mountains along the ill-defined Haitian border and engaged in guerilla raids, eventually recapturing most of the Cibao. Heavy-handed religious reforms promulgated by the Spanish Archbishop, discrimination against the mulatto majority, and unfavorable restrictions on trade all fed resentment of Spanish rule. The Spanish army was unable to defeat the guerillas, and its ranks were decimated by Yellow Fever; with the end of the American Civil War they were forced to withdraw. In 1865, independence from Spain was restored after four years of colonial reannexation.

Second Republic

By the time the Spanish departed, the main towns lay in ruins (particularly in the Cibao Valley) and the island was divided among several dozen caudillos who fought amongst themselves for power. In the course of these struggles, two parties emerged. The Partido Azul, which included most of the former guerilla leaders, represented the tobacco and cacao planters and merchants of the Cibao, and was receptive to liberal ideals. The Partido Rojo, dominated by Buenaventura Báez, represented the southern cattle ranching latifundia and mahogany exporting interests and sought to maintain an autocratic form of government. From the Spanish withdrawal to 1879, there were twenty-one changes of governments and at least fifty military uprisings. [5] Báez served as President briefly in 1865-66, and for longer periods in 1868-74 and 1878-79. During his second term, in 1871, he signed a treaty annexing the country to the United States. Supported by Ulysses S. Grant and his powerful Secretary of State William Seward, who hoped to establish a Navy base at Samana, it was defeated in the U.S. Senate. In 1879, the leader of the Partido Azul, General Gregorio Luperón, seized power. Ruling the country from his hometown of Puerto Plata, enjoying an economic boom due to increased tobacco exports to Germany, he enacted a new constitution that set a two-year presidential term limit, suspended the semi-formal system of bribes and initiated construction on the nations first railroad, with its terminus at the port of Sanchez on Samaná Bay.

The Ten Years' War in Cuba, from 1868 to 1878, brought Cuban sugar planters to the country in search of new sugar lands and security from the insurrection that freed their slaves and destroyed their property. Many settled in the southeastern coastal plain, and, with assistance from Luperón’s government, established the nation's first mechanized sugar mills, in 1879 and 1882. Over the following two decades, the sugar industry brought new prosperity to the region, transforming the former fishing hamlets of San Pedro de Macorís and La Romana into thriving ports. As the sugar plantations grew in number and size, they began to employ migrant laborers from the British, Dutch and Danish West Indies, in particular Turks and Caicos, the Virgin Islands, St. Martin, and St. Kitts (refered to by Dominicans as cocolos), during the harvest season. [6]

Allying with the emerging sugar interests, the dictatorship of General Ulises Heureaux, popularly known as Lilís, brought unprecedented stability to the island through iron-fisted rule that lasted almost two decades. The son of a Haitian father and a mother from St. Thomas, Lilís was distinguished by his blackness from most other contenders for power, with the exception of Luperón. A former lieutenant of Luperón, he served as President from 1882-1883, 1887 and 1889-1899, welding power through a series of puppet presidents when not occupying the office. In 1889, Lilís imposed constitutional ammendments abolishing direct presidential elections and term limits. Incorporating leaders of both the Rojos and Azules into his government while developing an extensive network of spies and informants to crush all potential opposition, he destroyed the Dominican Republic's incipient party system through a combination cooptation and terror. Aided by the newfound prosperity, his government undertook a number of infrastructural projects, including the electrification of Santo Domingo, the construction of a bridge over the Ozama River and the completion of a railroad linking Santiago and Puerto Plata.[7]

Lilís brought the government to its knees by borrowing heavily-at unfavorable interest rates-from European and American banks-in order to enrich himself, stabilize the existing debt, strengthen the bribe system, pay for the army, finance infrastructural development and help set up sugar mills. When his principle European creditor, the Amsterdam-based Westendorp Co., went bankrupt in 1893, he was forced to mortage the nation's customs fees to a New York financial firm called the San Domingo Improvement Co.. In 1899, when Lilís was assassinated by the Cibao tobacco merchants he had been begging for a loan from, the country's debt was over $35 million, four times the annual budget. After his death, the country returned to the cycle of chronic civil strife; the Cibao politicians who led the revolt against Heureaux-the nation's wealthiest tobacco planter Juan Isidro Jimenez and General Horacio Vásquez-after being named president and vice-president, quickly fell out over the division of spoils. The six years after Lilís' death witnessed four revolutions and five different presidents. [8]

With the nation on the brink of defaulting, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands sent warships to Santo Domingo to press the claims of their nationals. In order to preempt military intervention, Theodore Roosevelt introduced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, declaring that the U.S. would assume responsibility for ensuring that the nations of Latin America met their financial obligations, by force if necessary. In January 1905, U.S. took over administration of the Dominican Republic's customs house, the major source of government revenues. Under this agreement, a Receiver-General, appointed by the U.S. President, would keep 55% of total revenues to pay off foreign claimants, while remitting 45% to the Dominican government. After two years, the U.S.-controlled Customs Receivership reduced the nations external debt to $17 million. [9] In 1907, this agreement was converted into a treaty, transferring control over customs receivership to the U.S. Bureau of Insular Affairs and providing of a loan of $20 million from a New York bank, as payment for outstanding claims, placing the U.S. in the position of being the Dominican Republic’s only foreign creditor. [10] In 1906, the election of Horacista vice-president Ramon Cáceres led to a period of political stability and renewed economic growth, aided by new American investment in sugar industry. However, Cáceres was murdered by his Minister of War, the Jimenista General Desiderio Arías in 1910. Jimenez ruled the country indirectly through a series of puppet president but, in 1913, Vásquez returned from exile in Puerto Rico and organized a new rebellion in the Cibao. The fiscal reserves of more than 4 million pesos left by Cáceres were soon spent to fight this civil war. [11] In June 1914 U.S. President Woodrow Wilson issued a three month ultimatium for the two opposing sides to end hostilities and agree on a new president, or have the U.S. impose one. Jimenez was elected in October, and soon faced new U.S. demands: appointment of an American director of public works and financial advisor; expansion of the authority of the Customs Receivership to the collection of internal revenue, and the creation of a new military force commanded by U.S. officersl. However, the Dominican Congress rejected these demands, and reinstated Minister of War Desiderio Arías staged a military coup in April, providing the pretext for the U.S. to occupy the Dominican Republic.

U.S. occupation

In order to 'protect foreign lives and property,' the Marines landed in Santo Domingo on May 15. Refusing the exercise an office 'regained with foreign bullets,' Jimenes resigned. [12] By the end of the month, U.S. warships were located off ever major port; on the first day of June, U.S. foreces occupied Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata, and, after a brief campaign, took Arias's stronghold Santiago by the beginning of July. The Dominican Congress elected Dr. Francisco Henríquez Carvajal as President; in November, after he refused to meet the American demands, Woodrow Wilson announced the imposition of a U.S. military government, with Rear Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp as Military Governor. The American military government implimented many of the institutional reforms carried out in the U.S. during the Progressive Era. These included reorganization of the tax system, accounting and administration, expansion of primary education, and the construction of a national system of highways. At the same time, U.S. military authorities imposed strict censorship laws, imprisoned opponents of the occupation and enacted a number of deeply unpopular measures, including bans on firearms and cockfighting. In 1920, U.S. authorities enacted a Land Registration Act, which, by enforcing laws requiring legal titles to land, forcibly dispossessed thousands of peasants lacking formal deeds to the lands they occupied. The principle legacy of the occupation was the creation of a National Police Force, used by the Marines to help fight against the various guerillas, and later the principle vehicle for the rise of Trujillo. In the southeast, the American occupation was opposed by a number of highly organized Gavillero bands, who harassed the invaders during the duration of the occupation and were never fully subjugated. At any given time, the U.S. faced eight to twelve guerilla leaders in the region, each of whom commanded several hundred followers. However, rivalries between various guerilla caudillos occasionally led them to fight against one another, and even cooperate with occupation authorities.

In spite of this continual war, their was an economic boom during the U.S. occupation. In what was referred to as 'la danza de los milliones,' sugar prices rose to their highest level in history, with the destruction of European sugar-beet farms during World War I. The price of sugar rose from $5.50 in 1914 to $22.50 in 1920, and Dominican sugar exports increased from 122,642 tons in 1916, at the outset of the occupation, to 158,803 tons in 1920, earning a record $45.3 million. [13] However, European beet sugar production quickly recovered, which, coupled by the growth of global sugar cane production, glutted the world market and caused sugar prices to plummet to only $2.00 by the end of 1921. This crisis drove most smaller Dominican and Cuban sugar planters to bankruptcy, allowing the larger, more heavily capitalized American estates to expand their holdings. By 1925, twelve U.S.-owned companies owned more than 81 percent of total sugar acreage, while the U.S. market received 98 percent of sugar exports. [14] After a strike in August 1921 by cocolo sugar cane workers organized by supporters of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, sugar companies increasingly relied on Haitian migrant laborers.

In the 1920 Presidential election Republican candidate Warren Harding criticized the occupation and promised eventual U.S. withdrawal. While Jimenez and Vásquez had sought to negotiate with the U.S., the recession discredited the military government and inspired a new nationalist political campaign, led by Dr. Henríquez and receiving widespread support from the Dominican elite, demanding unconditional withdrawal pura y simple. They formed alliances with frustrated nationalists in Puerto Rico and Cuba, as well as critics of the occupation in the U.S. itself, most notably The Nation and the Haiti-San Domingo Independence Society.

1930 to 1980

The occupation ended in 1924, with a democratically elected Dominican government under president Horacio Vasquez (1924 - 1930). The initial American demands to maintain control over the National Police force were refused, although they retained control over the nation's customs. In an effort to undercut his primary rival, Federico Velásquez, and to preserve power for his supporters, Vásquez agreed in 1927 to a prolongation of his term from four to six years. There was some debatable legal basis for the move, which was approved by the Congress, but its enactment effectively invalidated the constitution of 1924 that Vásquez had previously sworn to uphold. The Great Depression resulted in a collapse in world prices for Dominican exports and decimated the countries economy; although elections were scheduled for May 1930, Vásquez's extension of power cast doubts about their fairness. In February, a revolution was proclaimed in Santiago by Rafael Estrella Ureña. The commander of the National Army (the new designation of the armed force created under the occupation), Rafael Trujillo, ordered his troops to remain in their barracks, Vásquez was forced into exile and Estrella elected provisional president. In May, Trujillo was elected with 95% of the vote, using the army to harass and intimidate electoral personnel and potential opponents. After his innauguration in August, at his request, the Dominican Congress proclaimed the beginning of the 'Era of Trujillo.'

The Era of Trujillo

Rafael Trujillo established absolute political control, while promoting economic development--from which mainly he and his supporters benefitted--and severe repression of domestic human rights.[15] By the late 1950's, Trujillo had at least seven categories of intelligence agenies, spying on each other as well as the public. At the same time, the Trujillo government spent half of its budget on a military that was one of the largest in Latin America. All citizens were obliged to carry identification cards and good-conduct passes from the secret police. The only legal political party, the Partido Dominicana, served as the arm of the regime, but was largely treated by Trujillo as a rubber-stamp for his decisions.

Obsessed with adulation, Trujillo promoted a cult of personality that elevated him to demigod status. When a hurricane destroyed much of Santo Domingo in 1935, he rebuilt and modernized the city, renaming it Ciudad Trujillo; he also renamed the countries highest mountain, Pico Duarte, as Pico Trujillo. The system of associating Trujillo with the countries material progress was institutionalized by the declaration of the 'Era of Trujillo, Benefactor of the Fatherland,' in January 1939, an inscription that all public works projects were required to bear.[16]

In 1937, Trujillo ordered the massacre of 20,000-25,000 Haitians, citing Haiti's support for Dominican exiles plotting to overthrow his regime. [17] During the European Holocaust in the Second World War, the Dominican Republic took in many Jews fleeing Hitler who had been refused entry by other countries. This decision was partially a result of the policy of blanquismo, designed to whiten the Dominican population through immigration. As part of the Good Neighbor Policy, in 1940, the State Department signed a treaty with Trujillo relinquishing control over the nations customs. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor Trujillo followed the U.S. in declaring war on the Axis powers, even though he had openly professed admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. During the Cold War, he maintained close ties to the U.S. by declaring himself the preeminent anti-communist in the Western Hemisphere and providing sanctuary for Fulgencio Batista after the Cuban revolution.

Trujillo and his family established a near-monoply over the national economy. By the time of his death, he had accumulated a fortune of around $800 million; he and his family owned 50-60 percent of the arable land (some 700,000 acres), and Trujillo-owned businesses accounted for 80% commercial activity in the capital.[18] He operated monopolies on sugar, salt, rice, milk, cement, insurance, tobacco, coffee, and insurance; owned two large banks, hotels, sugar refineries, port facilities, an airline and shipping line; deducted 10% of all public employees' salaries (ostensibly for his party); and received a portion of prostitution revenues. [19] World War II brought increased demand for Dominican exports, and the 1940's and early 1950's witnessed economic growth and considerable expansion of the nations infrastructure, although 'it was hardly coincidental that new roads often led to Trujillo's plantations and factories, and new harbors benefited Trujillo's shiping and export enterprises.'[20] Trujillo transformed Santo Domingo from an administrative center to the national center of shipping and industry. Mismanagement and corruption resulted in major economic problems. By the beginning of the 1960's, the economy had begun to deteriorate due to a combination of overspending on a festival to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the regime, overspending to buy privately owned sugar mills and electricity plants, and a decision to make a major investment in state sugar production that proved economically unsuccessful.

In August 1960, the Organization of American States (OAS) imposed diplomatic sanctions against the Dominican Republic as a result of Trujillo's complicity in an attempt to assassinate President Rómulo Betancourt of Venezuela. These sanctions remained in force after Trujillo's assassination in May 1961. In November 1961, the Trujillo family was forced into exile, fleeing to France.

The Post-Trujillo Era

In January 1962, a council of state with legislative and executive powers was formed; it included moderate members of the opposition. OAS sanctions were lifted January 4, and, after the resignation of President Joaquín Balaguer on January 16, the council under President Rafael Filiberto Bonnelly headed the Dominican government. In 1963, Juan Bosch of the Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (Dominican Revolutionary Party, or PRD) was inaugurated President, only to be overthrown by a right-wing military coup in September 1963.[21]

After Bosch's overthrow a supposedly civilian triumvirate established a de facto dictatorship until April 24 1965, when another military coup led to violence between military elements favoring the return to government by Bosch and those who proposed a military junta committed to early general elections. On April 28, after being requested by the anti-Bosch army elements, U.S. military forces landed, officially to protect U.S. citizens and to evacuate U.S. and other foreign nationals in what was known as Operation Power Pack. Additional U.S. forces subsequently imposed political stability on the country.

In June 1966, President Balaguer, leader of the Reformist Party (now called the Social Christian Reformist Party--PRSC), was elected and then re-elected to office in May 1970 and May 1974, both times after the major opposition parties withdrew late in the campaign because of the high degree of violence by pro-government groups. Balaguer led the Domincan Republic through a thorough economic restructuring, based on opening the country to foreign investment while protecting state-owned industries and certain private interests. This distorted, dependent development model produced uneven results. For most of Balaguer's nine years in office the country experienced high growth rates (e.g., an average GDP growth rate of 9.4 percent between 1970 - 1975), to the extent that people talked about the "Dominican miracle." Foreign--mostly U.S.--investment, as well as foreign aid, flowed into the country and sugar (then the country's main export product) also enjoyed good prices in the international market. However, this excellent macroeconomic performance was not accompanied by an equitable distribution of wealth. While a group of new millionaires flourished during Balaguer's administrations, the poor simply became poorer. Morever, the poor were commonly the target of state repression, and their socioeconomic claims were labeled "communist" and dealt with appropriately by the state security apparatus.[22]

In the May 1978 election, Balaguer was defeated in his bid for a fourth successive term by Antonio Guzmán Fernández of the PRD. Guzmán's inauguration on August 16 marked the country's first peaceful transfer of power from one freely elected president to another.

1980—present

The PRD's presidential candidate, Salvador Jorge Blanco, won the 1982 elections, and the PRD gained a majority in both houses of Congress. In an attempt to cure the ailing economy, the Jorge administration began to implement economic adjustment and recovery policies, including an austerity program in cooperation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In April 1984, rising prices of basic foodstuffs and uncertainty about austerity measures led to riots in which an estimated one hundred people were killed by the government's troops.

Balaguer was returned to the presidency with electoral victories in 1986 and 1990. Upon taking office in 1986, Balaguer tried to reactivate the economy through a public works construction program. Nonetheless, by 1988, the country slid into a 2-year economic depression, characterized by high inflation (59.5 percent in 1989) and currency devaluation.[23] Economic difficulties, coupled with problems in the delivery of basic services--including electricity, water, and transportation--generated popular discontent that resulted in frequent protests, occasionally violent, including a paralyzing nationwide strike in June 1989.

In 1990, Balaguer instituted a second set of economic reforms. After concluding an IMF agreement, balancing the budget, and curtailing inflation, the Dominican Republic is experiencing a period of economic growth marked by moderate inflation, a balance in external accounts, and a steadily increasing GDP.

The voting process in 1986 and 1990 was generally seen as fair, but allegations of electoral board fraud tainted both victories. The elections of 1994 were again marred by charges of fraud, this time amid documented charges from the Partido de la Liberacion Dominicana (Dominican Liberation Party, or PLD) that as many as 200,000 of its sympathizers had been disfranchised and prevented from voting. Following a compromise calling for constitutional and electoral reform, President Balaguer assumed office for an abbreviated term. With Balaguer prevented from running, the June 1996 presidential election was won by Leonel Fernández Reyna of the PLD. In May 2000 the PRD's Hipólito Mejía was elected to a 4-year term as president. His presidency saw major inflation and instability of the peso. During his time as president, the relatively stable unit of currency fell from ~ 16 DOP (Dominican Pesos) to 1 USD (United States Dollar) to ~ 60 DOP to 1 USD, and was in the 50s to a dollar when he left office. In May 2004, Leonel Fernández Reyna was again elected to a 4-year term as president and inaugurated on August 16, 2004. Reyna's administration has since then managed to deflate the peso and has increased its stability since the administration of Mejía. The peso is currently at the exchange rate of ~31 DOP to 1 USD.

The Dominican Republic was involved in the US led coalition in Iraq, as part of the Spain-led Latin-American Plus Ultra Brigade, but in 2004, the nation pulled its 300 or so troops out of Iraq.

See also

Notes

Template:Explain-inote Template:Inote

- ^ Jonathan Hartlyn, The Struggle for Democratic Politics in the Dominican Republic, p.24, The University of North Carolina Press, 1998

- ^ Sugar Cane: Past and Present, Peter Sharpe http://www.siu.edu/~ebl/leaflets/sugar.htm

- ^ Knight, Franklin, The Caribbean: The Genesis of a Fragmented Nationalism, 3rd ed. p.54 New York, Oxford University Press 1990

- ^ Moya Pons, Frank Between Slavery and Free Labor: The Spanish-speaking Caribbean in the 19th Century. Baltimore; John Hopkins University Press 1985

- ^ Frank Moyna-Pons, Dominican Republic: A National History (Hispaniola Press: Santo Domingo) Pg. 222

- ^ cocolo is a corruption of one of the name of one of the principle islands of origin, Tortola Teresita Martinez-Vergne, Nation and Citizenship in the Dominican Republic, Pg. 86

- ^ Teresita Martínez-Vergne, Nation & Citizen in the Dominican Republic, Pg. 135

- ^ Howard Wirada, Dominican Reublic: A Nation in Transition (Pall Mall Press: London, 1966) Pg. 30

- ^ Capt. Stephen M. Fuller, Marines in the Dominican Republic, Pg. 5

- ^ Bruce Calder, The Impact of Intervention, Pg. 24

- ^ Frank Moya-Pons, Pg. 306

- ^ Bruce Calder, The Impact of Intervention In The Dominican Republic, 1916-1924 Pg. 8

- ^ Bruce Calder, The Impact of Intervention, Pg. 93

- ^ Ibid

- ^ Johathan Hartlyn. The Trujillo Regime in the Dominican Republic. In Sultanistic Regimes, Johns Hopkins University Press

- ^ Eric Paul Roorda, The Dictator Next Door: The Good Neighboor Policy and the Truillo Regime in the Dominican Republic, 1930-1945 Pg. 98

- ^ Jan Kippers Black, Pg. 27

- ^ The Dominican Republic: A Nation in Transition, Pg. 40-41

- ^ Jared Diamond, Collapse, 'One Island, Two Peoples, Two Histories' (Penguin Books: New York and London, 2005) Pg. 337

- ^ Jan Kippers Black, The Dominican Republic: politics and development in an unsovereign state' Pg. 27

- ^ Ernesto Sagas & Sintia Molina, Dominican Migration: Transnational Perpectives, University Press Florida 2004

- ^ Roberto Cassa, Los doce años: Contrarevolución y desarrollismo, 2nd ed. Santo Domingo: Editora Buho 1991

- ^ International Monetary Fund. Dominican Republic: Selected Issues, IMF Staff report No. 99/117, Washington DC 1999