The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology that existed during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity and the Middle Ages, declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

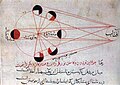

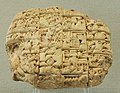

The earliest roots of scientific thinking and practice can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia during the 3rd and 2nd millennia BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed by the Scientific Revolution that transpired during the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

The Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men comprised ten volumes of Dionysius Lardner's 133-volume Cabinet Cyclopaedia (1829–1846). Aimed at the self-educating middle class, this encyclopedia was written during the 19th-century literary revolution in Britain that encouraged more people to read.

The Lives formed part of the Cabinet of Biography in the Cabinet Cyclopaedia. Within the set of ten, the three-volume Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men of Italy, Spain and Portugal (1835–37) and the two-volume Lives of the Most Eminent Literary and Scientific Men of France (1838–39) consist of biographies of important writers and thinkers of the 14th to 18th centuries. Most of them were written by the Romantic writer Mary Shelley. Shelley's biographies reveal her as a professional woman of letters, contracted to produce several volumes of works and paid well to do so. Her extensive knowledge of history and languages, her ability to tell a gripping biographical narrative, and her interest in the burgeoning field of feminist historiography are reflected in these works. (Full article...)

Selected image

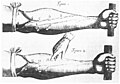

Der Quacksalber (The Quack) is a painting (oil on wood, 53 x 56 cm) by Franz Anton Maulbertsch, from some time before 1785. The subject, of course, is quackery—the peddling of unproven, and sometimes dangerous, medicines, cures or treatments— which has existed throughout the history of medicine. In ancient times, theatrics were sometimes mixed with actual medicine to provide entertainment as much as healing. Quack medicines often had little in the way of active ingredients, or had ingredients which made a person feel good, such as what came to be known as recreational drugs. Morphine and related chemicals were especially common, being legal and unregulated in most places at the time. Arsenic and other poisons were also included.

Did you know

...that the history of biochemistry spans approximately 400 years, but the word "biochemistry" in the modern sense was first proposed only in 1903, by German chemist Carl Neuberg?

...that the Great Comet of 1577 was viewed by people all over Europe, including famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe and the six year old Johannes Kepler?

...that the Society for Social Studies of Science (often abbreviated as 4S) is, as its website claims, "the oldest and largest scholarly association devoted to understanding science and technology"?

Selected Biography -

Edward Teller (Hungarian: Teller Ede; January 15, 1908 – September 9, 2003) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist and chemical engineer who is known colloquially as "the father of the hydrogen bomb" and one of the creators of the Teller–Ulam design inspired by Stanisław Ulam. He had a volatile personality, and was "driven by his megaton ambitions, had a messianic complex, and displayed autocratic behavior." He devised a thermonuclear Alarm Clock bomb with a yield of 1000 MT (1 GT of TNT) and proposed delivering it by boat or submarine to incinerate a continent.

Born in Austria-Hungary in 1908, Teller emigrated to the US in the 1930s, one of the many so-called "Martians", a group of Hungarian scientist émigrés. He made numerous contributions to nuclear and molecular physics, spectroscopy, and surface physics. His extension of Enrico Fermi's theory of beta decay, in the form of Gamow–Teller transitions, provided an important stepping stone in its application, while the Jahn–Teller effect and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) theory have retained their original formulation and are mainstays in physics and chemistry. Teller analyzed his problems using basic principles of physics and often discussed with his cohorts to make headway through difficult problems. This was seen when he worked with Stanislaw Ulam to get a workable thermonuclear fusion bomb design, but later temperamentally dismissed Ulam's aid. Herbert York stated that Teller utilized Ulam's general idea of compressive heating to start thermonuclear fusion to generate his own sketch of a workable "Super" bomb. Prior to Ulam's idea, Teller's classical Super was essentially a system for heating uncompressed liquid deuterium to the point, Teller hoped, that it would sustain thermonuclear burning. It was, in essence, a simple idea from physical principles, which Teller pursued with a ferocious tenacity even if he was wrong and shown that it would not work. To get support from Washington for his Super weapon project, Teller proposed a thermonuclear radiation implosion experiment as the "George" shot of Operation Greenhouse. (Full article...)

Selected anniversaries

- 1764 - Death of Nathaniel Bliss, English Astronomer Royal (b. 1700)

- 1768 - Death of Antoine Deparcieux, French mathematician (b. 1703)

- 1850 - Birth of Woldemar Voigt, German physicist (d. 1919)

- 1853 - Birth of Wilhelm Ostwald, German chemist, Nobel laureate (d. 1932)

- 1859 - A solar super storm affects electrical telegraph service

- 1865 - Death of William Rowan Hamilton, Irish mathematician (b. 1805)

- 1877 - Birth of Frederick Soddy, British chemist, Nobel laureate (d. 1956)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus