Utente:Panjabi/Prove

| Leopardo arabo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Stato di conservazione | |

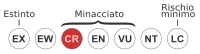

Critico[1] | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Ordine | Carnivora |

| Famiglia | Felidae |

| Genere | Panthera |

| Specie | P. pardus |

| Sottospecie | P. pardus nimr |

| Nomenclatura trinomiale | |

| Panthera pardus nimr (Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, 1833) | |

| Sinonimi | |

|

P. p. jarvisi Pocock, 1932 | |

Il leopardo arabo (Panthera pardus nimr Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, 1833) è una sottospecie di leopardo originaria della Penisola Araba; con meno di 200 esemplari rimasti nel 2006, è classificato tra le specie in pericolo critico. Classificato tra le specie in pericolo nel 1994 e tra quelle in pericolo critico nel 1996, il leopardo arabo compare nell'Appendice I della CITES [2] . È la più piccola sottospecie di leopardo [3] .

Panthera pardus nimr si è affermato come sottospecie distinta dopo le analisi genetiche compiute su un esemplare in cattività originario di Israele o dell'Arabia meridionale, le quali hanno mostrato una stretta parentela con il leopardo africano [4] .

Distribuzione e biologia

Fino alla fine degli anni '60 il leopardo arabo era molto diffuso in quasi tutta la Penisola Araba. Un tempo si incontrava anche nella parte settentrionale del Monte Libano (nell'Haqel), nell'Hijaz e sui Monti Sarawat [5] . Viveva anche sugli altopiani dello Yemen settentrionale, sui monti di Ras al-Khaima, nella regione orientale degli Emirati Arabi Uniti e sui Monti Jebel Samhan e Dhofar dell'Oman [5] . The presumed distribution of leopards in Arabia extends along the mountains from Haqel in the north-west of Arabia, down to Yemen, and in the mountains of Hadarmout to north-east of Oman and the eastern mountains of the United Arab Emirates. In Saudi Arabia, the leopard's habitat extends for about 1,700 km along the rugged arid to semi-arid mountains along the coast of the Red Sea. Leopards were found to occupy remote and rugged high-mountain areas that provided them with security and vantage points. The geographic range is poorly understood but generally considered as limited to the Arabian Peninsula, including Egypt's Sinai Peninsula. There is a very small population in Israel's Negev desert, estimated at 20 in the late 1970s.

The largest confirmed subpopulation inhabits the Dhofar Mountains of southern Oman. Each adult leopard has its own range, which it violently defends from other leopards of its own sex; however, a male's home range might overlap several other females' home ranges. Inside these ranges, the leopards hunt, mate, and raise young. In this arid terrain, they require large territories in order to find enough food, which means that even in the best of times the population is small and widespread.[2]

Anatomy

The leopard Panthera pardus is one of the most widely distributed and adaptable big cats in Oman. This cat has pelage hues that vary from pale yellow to deep golden or tawny and are patterned with rosettes.[6] At about 30 kg (65 pounds) for the male and around 20 kg (45 pounds) for the female, the Arabian leopard is much smaller than all of the African Leopard and Asian subspecies.[7]

It is listed as Critically Endangered, as the effective population size is clearly below 250 mature individuals, with a continuing decline, and severely fragmented distribution with isolated subpopulations not larger than 50 mature individuals.[7]

In the arid terrain of their habitat, Arabian leopards require large territories in order to find enough food and water to survive. The male's territory usually overlaps those of one or more females, and is fiercely defended against other intruding males, although spatial overlap between male ranges is common.[3]

Despite males and females sharing a range, they are solitary animals, only coming together to mate, which is very vocal and lasts for approximately five days.[8][9] After a gestation period of around 100 days, a litter of one to four cubs is born in a sheltered area, such as a small cave or under a rock overhang.[8][9] During the first few weeks the female frequently moves her cubs to different hiding places to reduce their risk of being discovered.[8] Although young open their eyes after about nine to ten days and begin to explore their immediate surroundings,[9] they will not venture from the security of the den until at least four weeks old.[3] Young are weaned at the age of three months but remain with their mother for up to two years whilst they learn the skills necessary to hunt and survive on their own.[3]

Diet and hunting

The Arabian leopard seems to concentrate on small-to-medium-sized prey species such as mountain gazelle, Arabian tahr, rock hyrax, hares, birds and possibly lizards and insects.[10] The carcass of a large prey is usually stored in caves or lairs but nothing was seen to be stored in trees.[10]

Threats and Conservation

A 2006 Arabian Fauna Conservation Workshop estimated there were fewer than 200 leopards remaining on the Arabian Peninsula, in three confirmed separate subpopulations.[2] The actual distribution of the leopard in Arabia is not known exactly, mainly due to habitat destruction, killing and lack of ecological studies.[11] Some reports indicate that the leopard population has decreased drastically in Arabia due to killing by shepherds and villagers after leopard raids on their livestock making them an enemy of farmers.[11] In addition, hunting of leopard prey, such as hyrax and ibex by local; inhabitant and habitat fragmentation, especially in the Sarawat Mountains, have made the survival of the leopard uncertain.[11] The reduced leopard population in Arabia requires immediate action to avoid further losses and extinction.[12] Recent reports point out that the numbers of leopards are decreasing drastically due to killing by hunters, and habitat degradation and fragmentation.[12] Together with the killing and poisoning of the leopard, decreased availability of prey might bring about its extinction.[10] Other reasons for killing leopards are for personal satisfaction and pride, traditional medicine and hides.[11] Some leopards are killed accidentally when eating poisoned carcasses intended for wolves and hyenas.[11]

A successful conservation strategy must promote the awareness of the importance of leopard conservation, employing the media and perhaps other sources for basic education programs. The support and involvement of people living close to leopard habitats are vital in such efforts. This is true not only because they might affect the conservation of the leopard in one way or another, but also because they depend on their livestock which could be killed occasionally by leopards. Although it is not always practical, compensation for lost livestock from leopard predation should be considered.[13]

Revenue from sources such as hunting rights and ecotourism, services such as roads and school employment in protected areas would encourage local residents to participate in leopard conservation. Furthermore, well-managed protected areas will ensure the continued survival of the species until other factors enhancing its survival become effective. Public awareness, fruitful consideration of the needs of local people and ecological studies may take years to be useful.[14]

The 4,500 km2 Jabal Samhan Nature Reserve was established there in 1997 after camera trap records of leopards were obtained; camera trapping since then has identified 17 individual adult leopards, including one cub. Camera trapping has also confirmed the presence of 9-11 leopards in the mountains that run west of the reserve to the Yemen border. At least ten wild leopards were live-captured in Yemen since the early 1990s and sold to zoos; some have been placed in conservation breeding centers in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.[2] Additionally, a detailed study of leopard distribution and habitat requirement is needed for the management of the species. The ecological information needed include data on feeding behavior, range use and reproduction. This information is of great importance to the survival of the species. There are many sites already surveyed and considered to be suitable for preservation for leopards in the plan adopted by the national commission for wildlife conservation and development. These areas include Jebel Fayfa, Jebel Al-Qahar, Jebel Shada, which has already been gazetted as a protected area, Jebel Nees, Jebel Wergan, Jebel Radwa and Harrat Uwayrid. The formal establishment of some of these areas is now urgent.[2]

Il leopardo arabo (Panthera pardus nimr) è una sottospecie di leopardo più piccola dei suoi cugini di Asia ed Africa. Questa sottospecie è criticamente minacciata e le sue popolazioni sono ancora in declino. Il leopardo arabo vive in Israele, Arabia Saudita, UAE, Yemen e Oman.

Habitat e comportamento

Non si trovano leopardi in aperto deserto e nelle boscaglie, ma invece vivono sulle alte montagne dell'Arabia, dove predano capre di montagna, volpi e altri animali di montagna. Sia i maschi che le femmine adulti posseggono un proprio territorio che difendono violentemente dagli altri leopardi dello stesso sesso; comunque, il territorio di un maschio si può sovrapporre a quello di alcune femmine. All'interno di questi territori, i leopardi cacciano, si accoppiano e allevano i piccoli. Su questi terreni aridi, essi necessitano di vasti territori per trovare cibo sufficiente, il che significa che anche in tempi migliori non ci siano mai stati molti leopardi in quest'area.

Anatomia

Di colore molto chiaro, è presente solo una colorazione giallo oro intenso tra le rosette nere presenti sul dorso dell'animale, mentre il resto del corpo varia dal beige al bianco-grigiastro. Con circa 30 kg per il maschio e circa 20 kg per la femmina, il leopardo arabo è molto più piccolo della maggior parte delle razze africane e asiatiche.

Alimentazione e caccia

Dal momento che molte delle loro prede naturali, come il tahr e la gazzella di montagna, sono virtualmente estinte, i leopardi arabi hanno spesso rivolto la loro attenzione al bestiame domestico, soprattutto alle capre, per il proprio sostentamento, entrando così in diretto conflitto con l'uomo. Predano anche volpi, od ogni altro piccolo mammifero o uccello, e possono anche nutrirsi facilmente di carogne. Questi animali elusivi cacciano soprattutto verso l'alba e il crepuscolo, ma rimangono attivi per tutta la notte, mentre trascorrono le ore calde della giornata in un luogo ombreggiato da cui possano osservare l'ambiente circostante.

Popolazione

Questa sottospecie di leopardo è criticamente minacciata. Il gran numero di uccisioni da parte dei cacciatori agli inizi degli anni '90 ha innescato un progetto di conservazione, guidato dall'Arabian Leopard Trust, che aiuta a preservare l'habitat montano con tutti i suoi abitanti. In tutta la penisola arabica la loro popolazione si aggira solamente sui 100 esemplari e nessuna sottopopolazione ha più di 50 individui. Malgrado questo, il loro numero sta ancora scendendo rapidamente. Persecuzioni e uccisioni per il controllo degli animali nocivi e anche cacce continuano ancora oggi. In Israele ne vivono 15-18 in tutto il Negev e l'Arava.

| Sciacallo egiziano [15] | |

|---|---|

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Ordine | Carnivora |

| Famiglia | Canidae |

| Genere | Canis |

| Specie | C. aureus |

| Sottospecie | C. a. lupaster |

| Nomenclatura trinomiale | |

| Canis aureus lupaster Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, 1833 | |

| Sinonimi | |

|

C. a. sacer Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, 1833 | |

Lo sciacallo egiziano (Canis aureus lupaster Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, 1833), noto anche come sciacallo lupo, è una sottospecie di sciacallo dorato originario di Egitto e delle regioni nordafricane circostanti, ma nel post Pleistocene il suo areale comprendeva anche la Palestina [16] .

Tassonomia

In passato, la questione se C. a. lupaster fosse un grosso sciacallo o un piccolo lupo è stata oggetto di numerosi dibattiti. Il primo a parlare di lupi in Egitto fu Aristotele, che li descrisse come animali più piccoli della razza greca. Georg Ebers scrisse che il lupo era uno degli animali sacri dell'Egitto, sottolineando che appartenesse ad una «varietà più piccola» di quella europea e facendo notare che il nome Lykopolis, la città dell'Antico Egitto dedicata ad Anubi, significa «città del lupo» [17] . Alcuni autori non considerano questa una prova attendibile dell'esistenza di lupi in Egitto, dato che tale nome venne conferito dai Greci e non dai fondatori egiziani [18] . Hemprich ed Ehrenberg, dopo aver notato varie somiglianze con gli sciacalli nordafricani ed i lupi, dettero alla specie il nome scientifico di Canis lupaster. Anche Thomas Henry Huxley, notando similitudini tra i crani del lupaster e dei lupi indiani, classificò questa specie come un lupo. Tuttavia, Ernst Schwarz, nel 1926, ritenne che il lupaster . Ferguson (1981) rejected this classification, and argued in favour of lupaster being a species of wolf, based on cranial measurements.[17] A comparative genetic analysis undertaken by the University of Leeds on Egyptian and Israeli jackals, as well as on wolves from Saudi Arabia and Oman, revealed that the classification of lupaster as a jackal could be valid, as there was a sequence divergence of only 4.8% between Egyptian and Israeli jackals.[19]

Description

It is a large subspecies standing some 41 cm (16 in) in shoulder-height, with a total length of about 127 cm (50 in),[20] thus exceeding the European jackal in size.[21] The skull is almost indistinguishable in size from that of the Indian Wolf, though the teeth of the Egyptian jackal are not as large.[22] The body is stoutly built, with proportionately short ears. The pelt is yellowish grey on the upper parts, and is mingled with black, which tends to collect in streaks and spots. The muzzle, the backs of the ears, and the outer surfaces of both pairs of limbs are reddish yellow, the margins of the mouth arc white, and the terminal half of the tail is darker than the back, with a black tip.[20] They do not form packs, instead being mostly found either singly or in pairs.[23]

Role in Egyptian culture

The Ancient Egyptian god of embalming, Anubis, was portrayed as a jackal-headed man, or as a jackal wearing ribbons and holding a flagellum. Anubis was always shown as a jackal or dog coloured black, the color of regeneration, death, and the night. It was also the color that the body turned during mummification. The reason for Anubis' animal model being canine is based on what the ancient Egyptians themselves observed of the creature - dogs and jackals often haunted the edges of the desert, especially near the cemeteries where the dead were buried. In fact, it is thought that the Egyptians began the practice of making elaborate graves and tombs to protect the dead from desecration by jackals. Duamutef, one of the Four Sons of Horus and a protection god of the Canopic jars, was also portrayed as having jackal-like features.

Author Michael Rice argues that the Egyptian jackal may have played a large part in the creation of Ancient Egyptian hunting hounds, pointing out how one specific breed (the Pharaoh hound), has vocalisations similar to golden jackals, including the latter species' ability to almost mimic the calls of their human masters. Among other similarities, Pharaoh hounds tend to give ritual "noddings and groanings" to people they encounter for the first time, and tend to be monogamous, and only choose to mate with members of the same breed.[18]

Descrizione

Solitamente presenta un manto grigio-beige molto sfumato o giallo sporco ed una corporatura molto esile. Si incontra molto raramente solo in aree localizzate. Pesa 10-15 kg. I naturalisti del passato, confusi dall'aspetto simile a quello del lupo arabo, ritennero che fosse imparentato con esso.[senza fonte] Attualmente non esistono leggi protettive riguardanti questo animale e le ultime stime dicono che rimangano ancora solamente 30-50 sciacalli egiziani.[senza fonte]

Ricerche e studi genetici

C. a. lupaster sembra essere la sottospecie di C. aureus di maggiori dimensioni (Ferguson, 1981). Lo sciacallo egiziano venne originariamente descritto come C. lupaster ed è più grosso, più pesante ed ha zampe più lunghe del C. aureus comune (Ferguson, 1981). Basandosi sulla forma del cranio, della mandibola e dei denti, Ferguson sostenne che questo taxon doveva essere considerato come una piccola specie di lupo del deserto. Ciò è alla base dell'errata classificazione dello sciacallo egiziano come una forma di lupo.

Soprattutto le caratteristiche del cranio e dei denti ne confermano l'appartenenza allo sciacallo dorato, nonostante la mandibola allungata e dal fondo piatto.

Una divergenza nella sequenza del 4,8% tra gli sciacalli egiziani e israeliani suggerisce che la designazione Canis aureus lupaster per gli sciacalli egiziani non è molto equilibrata. Inoltre, è stata riscontrata una certa ibridizzazione nelle popolazioni egiziane, la quale indica degli eventi di introgressione con altri sciacalli e cani inselvatichiti, o tra sciacalli e lupi grigi.

In uno studio è stata investigata la struttura genetica delle popolazioni di sciacallo dorato egiziano, la quale è stata confrontata con quella degli esemplari che vivono in Israele e con quella dei lupi dell'Arabia Saudita e dell'Oman. Le analisi tramite l'uso del citocromo b nell'mtDNA confermano che nelle popolazioni di sciacallo egiziano e di Israele non vi è alcuna variabilità genetica, ma solo dei differenti aplotipi, che indicano forse due indipendenti eventi di evoluzione a collo di bottiglia (Masters Courses in Biodiversity & Conservation, progetti egiziani).

Il lupo egiziano (Wilson & Reeder, 2005), sulla base delle ricerche del DNA, viene ora classificato come una sottospecie di sciacallo dorato e non di lupo grigio[1]. Lo sbaglio era stato causato dal caratteristico profilo da lupo grigio, con zampe lunghe ed orecchie più grandi di quelle degli altri sciacalli [2].

Mitologia

Lo sciacallo dorato egiziano potrebbe essere l'animale che nella mitologia egiziana ha dato gli attributi al dio Anubi.

Anubi veniva rappresentato come un uomo con la testa di uno sciacallo dorato. Il dio-sciacallo era una delle divinità più importanti.

Lo sciacallo dorato egiziano di Anubi era di colore nero, con lunghe orecchie e muso appuntito.

Note

- ^ (EN) Nowell, K., Breitenmoser-Wursten, C., Breitenmoser, U. (Cat Red List Authority) & Hoffmann, M. (Global Mammal Assessment Team) 2008, Panjabi/Prove, su IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Versione 2020.2, IUCN, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Mallon, D.P., Breitenmoser, U., Ahmad Khan, J. 2008. Panthera pardus ssp. nimr. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.2

- ^ a b c d Hellyer, P., Aspinall, S. (2005) The Emirates: A Natural History. Trident Press Limited, United Arab Emirates

- ^ Uphyrkina, O., Johnson, W. E., Quigley, H., Miquelle, D. , Marker, L., Bush, M., O'Brien, S. (2001) Phylogenetics, genome diversity and origin of modern leopard, Panthera pardus. Molecular Ecology (2001) 10: 2617–2633 download pdf.

- ^ a b Nader, I.A. (1989) Rare and endangered mammals of Saudi Arabia. In: Abu-Zinada, A. H., Goriup, P. D., Nader, I. A. (Eds.) Wildlife Conservation and Development in Saudi Arabia, no. 3. N.C.W.C.D. Publication, Riyadh, pp. 220–233

- ^ Seidensticker, J., Lumpkin, S. (1991) Great Cats. Merehurst, London.

- ^ a b Breitenmoser, U., Mallon, D., Breitenmoser-Würsten, C. (2006) A framework for the conservation of the Arabian leopard. Cat News Special Issue 1: 44-47.

- ^ a b c UAE Interact: Comprehensive news and information on the United Arab Emirates (April, 2006) http://www.uaeinteract.com/photofile/phf_arc16.asp

- ^ a b c Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife in Sharjah (April, 2006) http://www.breedingcentresharjah.com/Home.htm

- ^ a b c Kingdon, J. (1990) Arabian Mammals. A Natural History. Academic Press Ltd. (279pp)

- ^ a b c d e CAMP (2002). The threatened fauna of Arabia's mountain habitat, Final report. EPAA, UAE, Sharjah.

- ^ a b Sanborn, C. Hoogstral, H. (1953) Some mammals of Yemen and their parasites. Fieldiana Zoology 34 (1953): p. 229.

- ^ Anderson, D. Grove, A. (1989) Conservation of Africa: People, Politics and Practice. Cambridge University Press, New York.

- ^ Bailey, T. N. (1993) The African leopard: Ecology and Behavior of a Solitary Felid. Columbia University Press, New York.

- ^ (EN) D.E. Wilson e D.M. Reeder, Panjabi/Prove, in Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3ª ed., Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

- ^ The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals by Peter Ucko, G. Dimbleby, published by Aldine Transaction, 2007, ISBN 0202361691

- ^ a b Ferguson, W.W. 1981. The systematic of Canis aureus lupaster (Carnivora : Canidae) and the occurrence of Canis lupus in North Africa, Egypt and Sinai, Mammalia 4: 459-465.

- ^ a b Swifter than the arrow: the golden hunting hounds of ancient Egypt by Michael Rice, published by I.B.Tauris, 2006, ISBN 1845111168

- ^ The distribution and abundance of golden jackels in Egypt, Faculty of Biological Sciences, University of Leeds

- ^ a b The game animals of Africa (1908) by Richard Lydekker, published by London, R. Ward, limited

- ^ Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Greece (PDF), su lcie.org, WWF Greece. URL consultato il 31 luglio 2007.

- ^ The great and small game of India, Burma, and Tibet, (1907) by Richard Lydekker, published by London, R. Ward, limited

- ^ Volume 3 of The Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians: Including Their Private Life, Government, Laws, Arts, Manufacturers, Religion, Agriculture, and Early History : Derived from a Comparison of the Paintings, Sculptures, and Monuments Still Existing, with the Accounts of Ancient authors by Sir John Gardner Wilkinson, published by John Murray, 1847

Bibliografia

- Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds) Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition, Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt, A (Hoath, Richard, 2003), American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977 424 809 0

Altri progetti

- Wikispecies contiene informazioni su Panjabi/Prove

Collegamenti esterni

- The Wild Canines of Egypt (Mark Hunter) the Feature Story.

- Uniwersity of Leeds.Faculty of Biological sciences. Masters Courses in Biodiversity & Conservation. The distribution and abundance of golden jackels in Egypt. Abstract