Utente:Panjabi/Prove

| Rinoceronte di Sumatra [1] | |

|---|---|

Emi e Harapan, i rinoceronti di Sumatra dello Zoo di Cincinnati | |

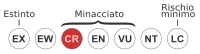

| Stato di conservazione | |

Critico[2] | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Ordine | Perissodactyla |

| Famiglia | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genere | Dicerorhinus Gloger, 1841 |

| Specie | D. sumatrensis |

| Nomenclatura binomiale | |

| Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (G. Fischer, 1814) [3] | |

| Areale | |

sull'areale attuale, indicato dalle aree rosso scuro, per vedere i nomi delle aree in cui vive il rinoceronte [4]

| |

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis G. Fischer, 1814), uno dei cinque rinoceronti esistenti, è una specie della famiglia dei Rinocerotidi. È l'unica specie del genere Dicerorhinus. Con un'altezza al garrese di 120 - 145 centimetri, una lunghezza di 250 centimetri e un peso di 500 - 800 chilogrammi, è di gran lunga il rinoceronte più piccolo. Come le specie africane, è dotato di due corni; quello sul naso, di maggiori dimensioni, è lungo solitamente 15 - 25 centimetri, mentre l'altro è quasi sempre ridotto a un moncone. Gran parte del corpo è ricoperta da una peluria marrone-rossastra.

Questo animale un tempo abitava le foreste pluviali, le paludi e le foreste della nebbia di India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Laos, Thailandia, Malaysia e Indonesia. In tempi storici si incontrava anche nelle regioni sud-occidentali della Cina, specialmente nel Sichuan [5][6] . Ora è gravemente minacciato e in natura ne rimangono solamente sei popolazioni di maggiore entità: quattro a Sumatra, una nel Borneo e un'altra nella Malaysia peninsulare. Il numero degli esemplari è difficile da valutare, poiché è una creatura solitaria che si sposta molto attraverso il proprio areale, ma è stato stimato che ne rimangano meno di 275 [7] . Il declino del rinoceronte di Sumatra va attribuito in prevalenza al bracconaggio per i suoi corni, di grandissimo valore nella medicina tradizionale cinese, valutati sul mercato nero non meno di 30.000 US$ [8] . Inoltre questa specie ha sofferto molto per la perdita dell'habitat: le foreste in cui viveva, infatti, sono state abbattute per ricavarne legname o per fare spazio alle coltivazioni.

Al di fuori del periodo del corteggiamento e dell'allevamento dei piccoli, il rinoceronte di Sumatra si rivela una creatura solitaria. È la specie di rinoceronte più loquace e inoltre comunica con i conspecifici calpestando il suolo con i piedi, piegando piccoli alberi o depositando escrementi. Conosciamo molto meglio le abitudini di questo rinoceronte rispetto a quelle del parimenti minacciato rinoceronte di Giava, soprattutto grazie ai 40 esemplari mantenuti in cattività allo scopo di salvaguardare la specie. Il programma di allevamento in cattività, però, venne considerato un disastro perfino dai suoi promotori; la maggior parte degli esemplari morì e il primo piccolo nacque solo dopo 20 anni: un calo demografico ancora peggiore rispetto a quello registrato in natura.

Tassonomia e sistematica

Il primo esemplare di rinoceronte di Sumatra di cui si abbia notizia venne ucciso in una località a 16 chilometri di distanza da Fort Marlborough, nei pressi della costa occidentale di Sumatra, nel 1793. Alcune raffigurazioni dell'animale e una descrizione scritta vennero inviate all'allora presidente della Royal Society di Londra, il naturalista Joseph Banks, che nello stesso anno pubblicò uno studio sull'esemplare. Fu solo nel 1814, comunque, che la specie ricevette un nome scientifico, da parte di Johann Fischer von Waldheim, uno scienziato tedesco curatore del Museo Statale Darwin di Mosca (Russia) [9][10] .

Il nome scientifico Dicerorhinus sumatrensis deriva dai termini greci di (δι, «due»), cero (κέρας, «corno») e rhinos (ρινος, «naso») [11] . Il nome sumatrensis deriva invece da Sumatra, l'isola indonesiana su cui questa specie venne scoperta per la prima volta [12] . In origine Carlo Linneo aveva classificato tutti i rinoceronti nel genere Rhinoceros e proprio per questo motivo il primo nome con cui venne chiamata la specie fu Rhinoceros sumatrensis. Poiché aveva due corni, però, nel 1828 Joshua Brookes ritenne giusto classificare il rinoceronte di Sumatra in un genere distinto da Rhinoceros, che comprende solo specie con un unico corno, a cui dette nome Didermocerus. Nel 1841 Constantin Wilhelm Lambert Gloger propose il nome Dicerorhinus. John Edward Gray, invece, nel 1868, propose di chiamarlo Ceratorhinus. Negli anni successivi il nome che ricevette maggior fortuna fu Didermocerus, quello proposto per primo, ma nel 1977 il Codice Internazionale di Nomenclatura Zoologica stabilì che bisognava utilizzare il nome Dicerorhinus [3][13] .

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra viene suddiviso in tre sottospecie:

- il D. s. sumatrensis, noto come rinoceronte di Sumatra occidentale, di cui rimangono solo 170 - 230 esemplari, in gran parte distribuiti nei parchi nazionali di Bukit Barisan Selatan e Gunung Leuser a Sumatra [7] . Altri 75 esemplari sopravvivono nella Malaysia peninsulare. I fattori che più minacciano questa sottospecie sono la distruzione dell'habitat e il bracconaggio. Tra i rinoceronti delle zone occidentali e orientali di Sumatra è presente una leggera differenza genetica [14] . In passato gli esemplari della penisola malese venivano attribuiti ad un'altra sottospecie, D. s. niger, ma successivamente è stata verificata la loro stretta parentela con gli esemplari più occidentali di Sumatra [3] ;

- il D. s. harrissoni, noto come rinoceronte di Sumatra orientale o rinoceronte del Borneo, un tempo molto diffuso in tutta l'isola del Borneo; attualmente si ritiene che ne sopravvivano solo 50 esemplari [7] . La popolazione più conosciuta risiede nel Sabah. Voci di avvistamenti non confermati, tuttavia, provengono anche dalle aree del Sarawak e del Kalimantan [15] . Questa sottospecie prende il nome da Tom Harrisson, scienziato che negli anni '60 lavorò intensamente a stretto contatto con zoologi e antropologi dell'isola [16] . Questa sottospecie ha dimensioni notevolmente più ridotte rispetto alle altre due [3] ;

- il D. s. lasiotis, noto come rinoceronte di Sumatra settentrionale, diffuso un tempo in India e Bangladesh, ma ormai dichiarato estinto in questi Paesi. In base a testimonianze non confermate si sospetta che potrebbe sopravviverne una piccola popolazione nel Myanmar, ma la situazione politica del Paese rende impossibile la verifica di tali voci [17] . Il nome lasiotis deriva da un termine greco che vuol dire «orecchie pelose». Studi successivi hanno dimostrato che i ciuffi sulle orecchie di questi animali non erano più lunghi di quelli degli altri rinoceronti di Sumatra, ma D. s. lasiotis rimase una sottospecie a tutti gli effetti, dato che presentava dimensioni notevolmente più grandi delle altre due [3] .

Evoluzione

I rinoceronti ancestrali si separarono dagli altri Perissodattili nell'Eocene Inferiore. Le analisi del DNA mitocondriale fanno ipotizzare che gli antenati dei rinoceronti moderni si separarono dalla linea evolutiva che avrebbe portato agli Equidi circa 50 milioni di anni fa [18][19] . L'attuale famiglia, i Rinocerotidi, fece la sua prima comparsa in Eurasia nell'Eocene Superiore e gli antenati delle specie attuali iniziarono a disperdersi nel resto del mondo nel Miocene [8][20] .

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra è ritenuto la specie più arcaica tra quelle oggi presenti e mostra molti tratti in comune con i suoi antenati del Miocene [8] . I resti fossili fanno datare la comparsa del genere Dicerorhinus al Miocene Inferiore, 23 – 16 milioni di anni fa. La datazione molecolare fa suggerire l'allontanamento di Dicerorhinus dalle altre quattro specie esistenti a non più di 25,9 ± 1,9 milioni di anni fa. Per spiegare le relazioni tra il rinoceronte di Sumatra e le altre specie attuali sono state fatte tre ipotesi. Una di queste sostiene che il rinoceronte di Sumatra sia maggiormente imparentato con i rinoceronti neri e bianchi dell'Africa, come testimonierebbe la presenza di due corni invece che di uno [18] . Altri tassonomi considerano il rinoceronte di Sumatra un sister taxon dei rinoceronti indiano e di Giava, a causa degli areali così sovrapposti o vicini [18][21] . Una terza ipotesi di pensiero, più recente, ipotizza tuttavia la presenza di tre lignaggi separati, le due specie africane, le due asiatiche e il rinoceronte di Sumatra, separatisi tra loro intorno ai 25,9 milioni di anni fa; quale gruppo si sia separato dagli altri per primo, tuttavia, non è ancora noto [18][22] .

A causa dell'aspetto così simile, in passato si credeva che il rinoceronte di Sumatra fosse imparentato da vicino con il rinoceronte lanoso (Coelodonta antiquitatis). Quest'ultimo, chiamato così per il folto mantello così simile a quello del rinoceronte di Sumatra, fece la sua prima comparsa in Cina e durante il Pleistocene Superiore si diffuse su tutto il continente eurasiatico, dalla Corea alla Spagna. Sopravvisse all'ultima era glaciale, ma, come il mammut lanoso, scomparve completamente circa 10.000 anni fa. Malgrado alcune differenze morfologiche [22] , recenti analisi molecolari hanno supportato l'ipotesi che le due specie siano sister taxa [23] . Molti resti fossili sono stati attribuiti a specie appartenenti a Dicerorhinus, ma attualmente ne sopravvive solo una [24] .

Descrizione

Un rinoceronte di Sumatra adulto misura 120 – 145 centimetri di altezza al garrese, è lungo 250 centimetri e pesa 500 – 800 chilogrammi, sebbene alcuni esemplari allevati negli zoo possano raggiungere anche i 1000 chilogrammi. Come le specie africane, è dotato di due corni. Il più grande è quello situato sul naso; è lungo generalmente solo 15 – 25 centimetri, ma in un caso documentato ha raggiunto gli 81 centimetri [25] . Il corno posteriore è molto più piccolo, non supera quasi mai i 10 centimetri, e spesso non è altro che un moncone. Il corno sul naso viene detto anche corno anteriore, mentre quello più piccolo viene detto frontale [24] . Il colore di questi corni è grigio scuro o nero. I maschi hanno corni più lunghi delle femmine, sebbene per il resto non sia presente dimorfismo sessuale. In natura il rinoceronte di Sumatra può vivere per 30 – 45 anni, mentre il record di sopravvivenza in cattività è attribuito a una femmina della sottospecie lasiotis, la quale morì a 32 anni e 8 mesi di età presso lo Zoo di Londra nel 1900 [24] .

Sul corpo, dietro le zampe anteriori e prima di quelle posteriori, sono presenti due pieghe di pelle spessa. Un'altra piega più piccola è situata intorno al collo. Anche la pelle stessa è molto spessa, 10 - 16 mm, e almeno in natura sembra che non sia presente alcuna sorta di grasso sottocutaneo. Il pelo può essere sia fitto (soprattutto negli esemplari giovanissimi) che rado, e solitamente è di color marrone-rossastro. In natura è molto difficile notarlo, poiché i rinoceronti sono spesso ricoperti di fango. In cattività, invece, diventa più folto e si fa più ispido, probabilmente perché non lo strofina camminando attraverso la fitta vegetazione. Due ciuffi di peli più lunghi si trovano attorno alle orecchie e alla fine della coda. Come tutti i rinoceronti, anche quello di Sumatra ha la vista molto scarsa. Tuttavia, è piuttosto veloce e agile; si arrampica facilmente sui terreni montuosi e valica con comodità pendici scoscese e argini fluviali [12][24][25] .

Distribuzione e habitat

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra vive nelle foreste pluviali secondarie, sia di pianura che di montagna, nelle paludi e nelle foreste della nebbia. Predilige le regioni collinari vicine all'acqua, soprattutto vallate circondate da ripidi pendii con un fitto sottobosco. Un tempo il suo areale si spingeva senza interruzioni verso nord, fino al Myanmar, all'India orientale e al Bangladesh. Testimonianze non confermate lo riferivano presente anche in Cambogia, Laos e Vietnam. Attualmente la sua presenza è accertata solamente nella Malaysia peninsulare, sull'isola di Sumatra e nel Sabah (Borneo). Alcuni conservazionisti sperano che qualche esemplare sopravviva ancora nel Myanmar, ma tale ipotesi sembra piuttosto remota. I tumulti politici all'interno del Paese hanno finora impedito qualsiasi sopralluogo o studio dei possibili esemplari sopravvissuti [26] .

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra è presente nel proprio areale in modo discontinuo, molto di più degli altri rinoceronti asiatici, il che rende difficilissimo ai conservazionisti proteggere effettivamente i pochi esemplari rimasti [26] . Sono note solamente sei aree in cui questo colosso sopravvive in maniera più consistente: i parchi nazionali di Bukit Barisan Selatan, Gunung Leuser, Kerinci Seblat e Way Kambas a Sumatra, il Parco Nazionale di Taman Negara nella Malaysia peninsulare e la Riserva Naturale di Tabin nel Sabah (Malaysia), sull'isola del Borneo [8][27] .

L'analisi genetica delle varie popolazioni ha permesso l'identificazione di tre differenti linee genetiche di rinoceronte di Sumatra [10] . Il canale tra Sumatra e la Malaysia non ha costituito una barriera insormontabile per queste creature quanto i Monti Barisan; per questa ragione i rinoceronti della regione orientale di Sumatra sono molto più simili geneticamente a quelli della Malaysia peninsulare che non a quelli della regione occidentale dell'isola. Queste due popolazioni mostrano una così scarsa variabilità genetica che probabilmente sono rimaste unite tra loro per tutto il Pleistocene. Le popolazioni di Sumatra e Malaysia, tuttavia, sono abbastanza simili tra loro da non far risultare problematico un possibile incrocio tra le due. I rinoceronti del Borneo, invece, sono così diversi dagli altri che i conservazionisti genetici si sono già mossi per evitare possibili incroci che potrebbero modificarne il patrimonio genetico [10] . Questi studiosi hanno recentemente iniziato a studiare la diversità del patrimonio genetico all'interno di queste popolazioni, individuando vari microsatelliti. I primi risultati delle analisi hanno riscontrato livelli di variabilità all'interno delle popolazioni di rinoceronte di Sumatra paragonabili a quelli trovati nei più numerosi rinoceronti africani, ma lo studio della diversità genetica di questa specie è tuttora in atto [28] .

Biologia

Tranne che nel periodo del corteggiamento e dell'allevamento dei piccoli, il rinoceronte di Sumatra è una creatura solitaria e territoriale. I territori dei maschi possono estendersi anche per 50 kmq, mentre quelli delle femmine sono vasti generalmente 10 – 15 kmq [12] . I territori delle femmine sembrano essere sempre ben distanziati tra loro; quelli dei maschi, invece, tendono spesso a sovrapporsi. Sembra che i rinoceronti di Sumatra non combattano mai tra loro per difendere i propri territori. I confini del territorio vengono segnalati grattando il suolo con le zampe, piegando alberelli in modo caratteristico e depositando cumuli di escrementi. Il rinoceronte di Sumatra è più attivo nei momenti in cui si nutre, all'alba e poco dopo il crepuscolo. Trascorre il giorno rinfrescandosi in pozze di fango o riposando. Durante la stagione delle piogge si sposta verso altitudini più elevate, per poi fare ritorno in pianura nei mesi più freddi [12] .

Questa specie trascorre molte ore del giorno stando immersa in pozze di fango. Se queste non sono disponibili, scava profonde depressioni con le zampe e i corni. Così facendo il rinoceronte si mantiene al fresco e protegge la pelle da ectoparassiti e altri insetti. Gli esemplari in cattività, privati della possibilità di fare questi bagni quotidiani, hanno rapidamente sviluppato screpolamento e infiammazione della pelle, suppurazioni, disturbi agli occhi e infiammazioni delle narici; molti di essi, infine, sono morti. Uno studio di 20 mesi sui bagni di fango fatti dal rinoceronte ha dimostrato che questo animale visita non più di tre pozze per volta. Dopo 2 - 12 settimane che utilizza la stessa pozza, il rinoceronte la abbandona. Generalmente, il colosso si immerge in questi stagni intorno a mezzogiorno e vi rimane per 2 - 3 ore prima di andare alla ricerca di cibo. Sebbene negli zoo il rinoceronte di Sumatra sia stato visto trascorrere nelle pozze meno di 45 minuti al giorno, gli studi effettuati in natura hanno dimostrato che ogni giorno rimane immerso per 80 - 300 minuti (in media 166) [29] .

Le opportunità di studiare l'epidemiologia del rinoceronte di Sumatra sono molto rare. Nel XIX secolo alcuni esemplari in cattività sono morti a causa di infezioni causate da zecche e Gyrostigma [25] . La specie si è inoltre dimostrata vulnerabile alla surra, una malattia ematica causata dai tripanosomi e trasmessa dai tafani; nel 2004 tutti e cinque gli esemplari presenti al Centro per la Conservazione del Rinoceronte di Sumatra, affetti da questa malattia, morirono dopo un periodo di 18 giorni [30] . Escluso l'uomo, il rinoceronte di Sumatra non ha predatori. Tigri e cuon sono in grado di uccidere i piccoli, ma questi rimangono sempre a stretto contatto con la madre e la frequenza delle uccisioni è sconosciuta. Sebbene l'areale del rinoceronte si sovrapponga a quello di elefanti e tapiri, queste specie non sembrano competere tra loro per il cibo o per l'habitat. Anzi, è noto che gli elefanti (Elephas maximus) e i rinoceronti condividano l'utilizzo degli stessi sentieri, utilizzati a loro volta anche da specie più piccole, come cervi, cinghiali e cuon [12][31] .

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra mantiene sgombri i sentieri che attraversano il suo territorio. Questi possono essere di due tipi: sentieri principali utilizzati da generazioni di esemplari per spostarsi tra le aree più importanti dell'areale, come i depositi di sale, o tra zone separate da terreni inospitali e sentieri più piccoli, spesso ricoperti dalla vegetazione, utilizzati per spostarsi all'interno delle aree di foraggiamento. Alcuni sentieri intersecano fiumi profondi anche 1,5 metri e larghi 50 metri. Spesso la corrente di questi fiumi è molto forte, ma il rinoceronte è un ottimo nuotatore [24][25] . Nelle aree popolate dai rinoceronti, la relativa assenza di pozze di fango nelle vicinanze dei fiumi indica che spesso questi animali fanno il bagno nel fiume invece del classico bagno di fango [31] .

Alimentazione

| Il rinoceronte di Sumatra si nutre di una vasta gamma di piante, come (in senso orario dall'alto a sinistra) Mallotus, mangostani, Ardisia ed Eugenia [31][32] | |

Il rinoceronte di Sumatra si nutre soprattutto poco prima del crepuscolo e nelle ore del mattino. È un brucatore e la sua dieta è composta da giovani alberelli, foglie, frutti, ramoscelli e germogli [24] . Ogni esemplare può consumare fino a 50 chilogrammi di cibo al giorno [12] . I ricercatori hanno identificato più di 100 specie di vegetali consumate da questa specie, soprattutto grazie all'analisi delle deiezioni. La maggior parte della dieta è composta da giovani alberelli con un diametro del tronco di 1 - 6 centimetri. Generalmente il rinoceronte schiaccia questi arboscelli con il peso del corpo, camminandoci sopra, per poi mangiarne le foglie. Molte delle specie consumate si trovano solo in percentuali molto basse, il che indica che il rinoceronte varia molto la dieta e la nutrizione a seconda delle località [31] . Tra le piante più comuni ricordiamo molte specie appartenenti alle famiglie di Euforbiacee, Rubiacee e Melastomatacee. Le specie più comuni in assoluto, tuttavia, appartengono a Eugenia [32] .

La dieta del rinoceronte di Sumatra è ricca di fibre e piuttosto carente di proteine [33] . I depositi di sale sono molto importanti per la nutrizione dell'animale. Questi si trovano nei pressi di sorgenti calde, infiltrazioni di acqua salata o vulcani di fango. Essi, inoltre, giocano anche un ruolo di importanza sociale: verso i depositi, infatti, si dirigono i maschi attratti dall'odore delle femmine in estro. Alcuni rinoceronti, tuttavia, vivono in aree dove i depositi di sale non sono molto frequenti; altri, invece, anche se abitano nei pressi di questi depositi, non sono soliti sfruttarli. Forse questi esemplari ricavano i minerali necessari da vegetali che ne sono particolarmente ricchi [31][32] .

Communication

| Sumatran Rhinoceros vocalizations (.wav files)[34] | |

|---|---|

The Sumatran Rhinoceros is the most vocal of the rhinoceros species.[34] Observations of the species in zoos show the animal almost constantly vocalizing and it is known to do so in the wild as well.[25] The rhino makes three distinct noises: eeps, whales, and whistle-blows. The eep, a short, one-second-long yelp, is the most common sound. The whale, named for its similarity to vocalizations of the Humpback Whale (see: Whale song), is the most song-like vocalization and the second most common. The whale varies in pitch and lasts from 4–7 seconds. The whistle-blow is named because it consists of a two-second-long whistling noise and a burst of air in immediate succession. The whistle-blow is the loudest of the vocalizations, loud enough to make the iron bars in the zoo enclosure where the rhinos were studied vibrate. The purpose of the vocalizations is unknown, though they are theorized to convey danger, sexual readiness, and ___location like other ungulate vocalizations do. The whistle-blow could be heard at a great distance even in the dense brush in which the Sumatran Rhino lives. A vocalization of similar volume from elephants has been shown to carry 9.8 km (6.1 miles) and thus the whistle-blow may carry as far.[34] The Sumatran Rhinoceros will sometimes twist saplings that they do not eat. This twisting behavior is believed to be used as a form of communication, frequently indicating a junction in a trail.[31]

Reproduction

Females become sexually mature at the age of 6–7 years, while males become sexually mature at about 10 years old. The gestation period is around 15–16 months. The calf, which typically weighs 40–60 kg (88–132 lb), is weaned after about 15 months and stays with the mother for the first 2–3 years of its life. In the wild, the birth interval for this species is estimated to be 4–5 years; its natural child-rearing behavior is unstudied.[12]

The reproductive habits of the Sumatran Rhinoceros have been studied in captivity. Sexual relationships begin with a courtship period characterized by increased vocalization, tail raising, urination and increased physical contact, with both male and female using their snouts to bump the other in the head and genitals. The pattern of courtship is most similar to that of the Black Rhinoceros. Young Sumatran Rhino males are often too aggressive with females, sometimes injuring and even killing them during the courtship. In the wild, the female could run away from an overly aggressive male, but in their smaller captive enclosures they cannot; this inability to escape aggressive males may partly contribute to the low success rate of captive breeding programs.[35][36][37]

The period of oestrus itself, when the female is receptive to the male, lasts about 24 hours and observations have placed its recurrence between 21–25 days. Rhinos in the Cincinnati Zoo have been observed copulating for 30–50 minutes, similar in length to other rhinos; observations at the Sumatran Rhinoceros Conservation Centre in Malaysia have shown a briefer copulation cycle. As the Cincinnati Zoo has had successful pregnancies, and other rhinos also have lengthy copulatory periods, a lengthy rut may be the natural behavior.[35] Though researchers observed successful conceptions, all these pregnancies ended in failure for a variety of reasons until the first successful captive birth in 2001; studies of these failures at the Cincinnati Zoo discovered that the Sumatran Rhino's ovulation is induced by mating and that it had unpredictable progesterone levels.[38] Breeding success was finally achieved in 2001 by providing a pregnant rhino with supplementary progestin.[39]

Conservation

Sumatran Rhinoceroses were once quite numerous throughout Southeast Asia. It is now estimated that less than 275 individuals remain.[7] Though not as rare as the Javan Rhinoceros, the Sumatran Rhinoceros faces greater poaching and habitat pressures and its populations are fragmented and small, whereas a substantial population of Javan Rhinoceros live together on the Ujung Kulon peninsula in Java. While the number of Javan Rhinos in Ujung Kulon has remained relatively stable, Sumatran Rhino populations are believed to be on the decline. It is classed as critically endangered primarily due to illegal poaching and destruction of its rainforest habitat. Most remaining habitat is in inaccessible mountainous areas of Indonesia.[40][41]

Poaching of Sumatran Rhinoceros, though less of a problem than with African Rhinoceros (least in terms of number of animals killed), is cause for concern because dealers are likely speculating that if the species becomes extinct then the price of its horn, estimated as high as $30,000 per kilogram,[8] could dramatically increase. The Sumatran Rhinoceros was never intensively hunted by European hunters. The rhinos are difficult to observe and hunt directly (one field researcher spent seven weeks in a treehide near a salt lick without ever observing a rhino directly), so poachers make use of spear traps and pit traps. In the 1970s, uses of the rhinoceros's body parts among the local people of Sumatra were documented, such as the use of rhino horns in amulets and a folk-belief that the horns offer some protection against poison. Dried rhinoceros meat was used as medicine for diarrhea, leprosy and tuberculosis. "Rhino-oil," a concoction made from leaving a rhino's skull in coconut oil for several weeks, may be used to treat skin diseases. The extent of use and belief in these practices is not known.[25][26][31] It was once believed that rhinoceros horn was widely used as an aphrodisiac; in fact traditional Chinese medicine never used it for this purpose.[8]

The rain forests of Indonesia and Malaysia, which the Sumatran Rhino inhabits, are also targets for legal and illegal logging because of the desirability of their hardwoods. Rare woods like merbau, meranti and semaram are valuable on the international markets, fetching as much as $1,800 per m3 ($1,375 per cu yd). Enforcement of illegal-logging laws is difficult because humans live within or nearby many of the same forests as the rhino. The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake has been used to justify new logging. Although the hardwoods in the rain forests of the Sumatran Rhino are destined for international markets and not widely used in domestic construction, the number of logging permits for these woods has increased dramatically because of the tsunami.[27]

In captivity

Though rare, Sumatran Rhinoceroses have been occasionally exhibited in zoos for nearly a century and a half. The London Zoo acquired two Sumatran Rhinoceros in 1872. One of these, a female named Begum, was captured in Chittagong in 1868 and survived at the London Zoo until 1900, the record lifetime in captivity for Sumatran Rhinos. At the time of their acquisition, Philip Sclater, the secretary of the Zoological Society of London claimed that the first Sumatran Rhinoceros in zoos had been in the collection of the Zoological Garden of Hamburg since 1868. Before the extinction of the subspecies Dicerorhinus sumatrensis lasiotis, at least seven specimens were held in zoos and circuses.[25] Sumatran Rhinos, however, did not thrive outside their native habitats. A rhino in the Calcutta Zoo successfully gave birth in 1889, but for the entire 20th century not one Sumatran Rhino was born in a zoo. In 1972, the only Sumatran Rhino remaining in captivity died at the Copenhagen Zoo.[25]

Despite the species' persistent lack of reproductive success, in the early 1980s some conservation organizations began a captive breeding program for the Sumatran Rhinoceros. Between 1984 and 1996 this ex situ conservation program transported 40 Sumatran Rhinos from their native habitat to zoos and reserves across the world. While hopes were initially high, and much research was conducted on the captive specimens, by the late 1990s not a single rhino had been born in the program and most of its proponents agreed the program had been a failure. In 1997, the IUCN's Asian Rhino specialist group, which once endorsed the program, declared that it had failed "even maintaining the species within acceptable limits of mortality," noting that, in addition to the lack of births, 20 of the captured rhinos had died.[8][26] In 2004, a surra outbreak at the Sumatran Rhinoceros Conservation Centre killed all the captive rhinos in peninsular Malaysia, reducing the population of captive rhinos to eight.[30][41]

Seven of these captive rhinos were sent to the United States (the other was kept in Southeast Asia), but by 1997, their numbers had dwindled to three: a female in the Los Angeles Zoo, a male in the Cincinnati Zoo, and a female in the Bronx Zoo. In a final effort, the three rhinos were united in Cincinnati. After years of failed attempts, the female from Los Angeles, Emi, became pregnant for the sixth time, with the zoo's male Ipuh. All five of her previous pregnancies ended in failure. But researchers at the zoo had learned from previous failures, and, with the aid of special hormone treatments, Emi gave birth to a healthy male calf named Andalas (an Indonesian literary word for "Sumatra") in September 2001.[42] Andalas's birth was the first successful captive birth of a Sumatran Rhino in 112 years. A female calf, named Suci (Indonesian for "pure"), followed on July 30, 2004.[43] On April 29, 2007, Emi gave birth a third time, to her second male calf, named Harapan (Indonesian for "hope") or Harry.[39][44] In 2007, Andalas, who had been living at the Los Angeles Zoo, was returned to Sumatra to take part in breeding programs with healthy females.[37][45]

Despite the recent successes in Cincinnati, the captive breeding program has remained controversial. Proponents argue that zoos have aided the conservation effort by studying the reproductive habits, raising public awareness and education about the rhinos, and helping raise financial resources for conservation efforts in Sumatra. Opponents of the captive breeding program argue that losses are too great; the program too expensive; removing rhinos from their habitat, even temporarily, alters their ecological role; and captive populations cannot match the rate of recovery seen in well-protected native habitats.[8][37]

Cultural depictions

Aside from those few individuals kept in zoos and pictured in books, the Sumatran Rhinoceros has remained little known, overshadowed by the more common Indian, Black and White rhinos. Recently, however, video footage of the Sumatran Rhinoceros in its native habitat and in breeding centers has been featured in several nature documentaries. Extensive footage can be found in an Asia Geographic documentary The Littlest Rhino. Natural History New Zealand showed footage of a Sumatran rhino, shot by freelance Indonesian-based cameraman Alain Compost, in the 2001 documentary The Forgotten Rhino, which featured mainly Javan and Indian rhinos.[46][47]

Though documented by droppings and tracks, pictures of the Bornean Rhinoceros were first taken and widely distributed by modern conservationists in April 2006 when camera traps photographed a healthy adult in the jungles of Sabah in Malaysian Borneo.[48] On April 24, 2007 it was announced that cameras had captured the first ever video footage of a wild Bornean Rhino. The night-time footage showed the rhino eating, peering through jungle foliage, and sniffing the film equipment. The World Wildlife Fund which took the video has used it in efforts to convince local governments to turn the area into a rhino conservation zone.[49][50] Monitoring has continued, with fifty new cameras set up and in February 2010 what appeared to be a pregnant rhino was filmed. Endangered pregnant Borneo rhino caught on camera, 21 April 2010.

A number of folk tales about the Sumatran Rhino were collected by colonial naturalists and hunters from the mid 1800s to early 1900s. In Burma, the belief was once widespread that the Sumatran Rhino ate fire. Tales described the fire-eating rhino following smoke to its source, especially camp-fires, and then attacking the camp. There was also a Burmese belief that the best time to hunt was every July when the Sumatran Rhinos would congregate beneath the full moon. In Malaya it was said that the rhino's horn was hollow and could be used as a sort of hose for breathing air and squirting water. In Malaya and Sumatra it was once believed that the rhino shed its horn every year and buried it under the ground. In Borneo, the rhino was said to have a strange carnivorous practice: after defecating in a stream it would turn around and eat fish that had been stupefied by the excrement.[25]

References

- ^ (EN) D.E. Wilson e D.M. Reeder, Panjabi/Prove, in Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3ª ed., Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, ISBN 0-8018-8221-4.

- ^ (EN) van Strien, N.J. & Talukdar, B.K. (Asian Rhino Red List Authority) 2008, Panjabi/Prove, su IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Versione 2020.2, IUCN, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Rookmaaker, L.C., The taxonomic history of the recent forms of Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), in Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 57, n. 1, 1984, pp. 12–25.

- ^ Derivata da una mappa presente su:

- Thomas J. and van Strien, Nico Foose, Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 1997, ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

and - Eric Dinerstein, The Return of the Unicorns; The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros, New York, Columbia University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

Questa mappa non tiene conto di alcuni avvistamenti in tempi storici in Laos e Vietnam o di eventuali popolazioni sopravvissute in Myanmar.

- Thomas J. and van Strien, Nico Foose, Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 1997, ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- ^ The Art of Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China (1999), p. 27. Jan Chapman. Christie’s Books, London.

- ^ The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics (1963), p 83. Edward H. Schafer. University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. First paperback edition: 1985.

- ^ a b c d Errore nelle note: Errore nell'uso del marcatore

<ref>: non è stato indicato alcun testo per il marcatoreIUCN - ^ a b c d e f g h Eric Dinerstein, The Return of the Unicorns; The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros, New York, Columbia University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

- ^ Rookmaaker, Kees, First sightings of Asian rhinos, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, p. 52.

- ^ a b c Juan Carlos Morales, Patrick Mahedi Andau, Jatna Supriatna, Zainuddin Zainal-Zahari, and Don J. Melnick, Mitochondrial DNA Variability and Conservation Genetics of the Sumatran Rhinoceros, in Conservation Biology, vol. 11, n. 2, 1997, pp. 539–543, DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.96171.x.

- ^ Henry G. Liddell, and Robert Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1980, ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g van Strien, Nico, Sumatran rhinoceros, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, pp. 70–74.

- ^ International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (1977). "Opinion 1080. Didermocerus Brookes, 1828 (Mammalia) suppressed under the plenary powers". Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 34:21–24.

- ^ Asian Rhino Specialist Group (1996). Dicerorhinus sumatrensis ssp. sumatrensis. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2007. Retrieved on January 13, 2008. Archiviato il 20080627173647 su www.iucnredlist.org URL di servizio di archiviazione sconosciuto.

- ^ Asian Rhino Specialist Group (1996). Dicerorhinus sumatrensis ssp. harrissoni. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2007. Retrieved on January 13, 2008. Archiviato il 20080627171433 su www.iucnredlist.org URL di servizio di archiviazione sconosciuto.

- ^ Groves, C.P., Description of a new subspecies of Rhinoceros, from Borneo, Didermocerus sumatrensis harrissoni, in Saugetierkundliche Mitteilungen, vol. 13, n. 3, 1965, pp. 128–131.

- ^ Asian Rhino Specialist Group (1996). Dicerorhinus sumatrensis ssp. lasiotis. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2007. Retrieved on January 13, 2008. Archiviato il 20080627171428 su www.iucnredlist.org URL di servizio di archiviazione sconosciuto.

- ^ a b c d Tougard, C., T. Delefosse, C. Hoenni, and C. Montgelard, Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA genes, in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 19, n. 1, 2001, pp. 34–44, DOI:10.1006/mpev.2000.0903.

- ^ Xu, Xiufeng, Axel Janke, and Ulfur Arnason, The Complete Mitochondrial DNA Sequence of the Greater Indian Rhinoceros, Rhinoceros unicornis, and the Phylogenetic Relationship Among Carnivora, Perissodactyla, and Artiodactyla (+ Cetacea), in Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 13, n. 9, 1º November 1996, pp. 1167–1173. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ Lacombat, Frédéric, The evolution of the rhinoceros, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Groves, C. P., Phylogeny of the living species of rhinoceros, in Zeitschrift fuer Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung, vol. 21, 1983, pp. 293–313.

- ^ a b Esperanza Cerdeño, Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla) (PDF), in Novitates, n. 3143, American Museum of Natural History, 1995.

- ^ Orlando, Ludovic, Jennifer A. Leonard, Aurélie Thenot, Vincent Laudet, Claude Guerin, and Catherine Hänni, Ancient DNA analysis reveals woolly rhino evolutionary relationships, in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 28, n. 2, September 2003, pp. 485–499, DOI:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00023-X.

- ^ a b c d e f Groves, Colin P., and Fred Kurt, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (PDF), in Mammalian Species, n. 21, American Society of Mammalogists, 1972, pp. 1–6, DOI:10.2307/3503818.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i N.J. van Strien, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis (Fischer), the Sumatran or two-horned rhinoceros: a study of literature, in Mededelingen Landbouwhogeschool Wageningen, vol. 74, n. 16, 1974, pp. 1–82.

- ^ a b c d Thomas J. and van Strien, Nico Foose, Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 1997, ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- ^ a b Dean, Cathy, Tom Foose, Habitat loss, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Scott, C., T.J. Foose, C. Morales, P. Fernando, D.J. Melnick, P.T. Boag, J.A. Davila, P.J. Van Coeverden de Groot, Optimization of novel polymorphic microsatellites in the endangered Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), in Molecular Ecology Notes, vol. 4, 2004, pp. 194–196, DOI:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2004.00611.x.

- ^ S.C. Julia Ng, Z. Zainal-Zahari, and Adam Nordin, Wallows and Wallow Utilization of the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus Sumatrensis) in a Natural Enclosure in Sungai Dusun Wildlife Reserve, Selangor, Malaysia, in Journal of Wildlife and Parks, vol. 19, 2001, pp. 7–12.

- ^ a b Vellayan, S., Aidi Mohamad, R.W. Radcliffe; L.J. Lowenstine, J. Epstein, S.A. Reid, D.E. Paglia, R.M. Radcliffe, T.L. Roth, T.J. Foose, M. Khan, V. Jayam, S. Reza, and M. Abraham, Trypanosomiasis (surra) in the captive Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis sumatrensis) in Peninsular Malaysia, in Proceedings of the International Conference of the Association of Institutions for Tropical Veterinary Medicine, vol. 11, 2004, pp. 187–189.

- ^ a b c d e f g Borner, Markus, A field study of the Sumatran rhinoceros Dicerorhinus sumatrensis Fischer, 1814: Ecology and behaviour conservation situation in Sumatra, Zurich : Juris Druck & Verlag, 1979, ISBN 3260046003.

- ^ a b c Yook Heng Lee, Robert B. Stuebing, and Abdul Hamid Ahmad, The Mineral Content of Food Plants of the Sumatran Rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) in Danum Valley, Sabah, Malaysia, in Biotropica, vol. 3, n. 5, The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, 1993, pp. 352–355, DOI:10.2307/2388795.

- ^ Dierenfeld, E.S., A. Kilbourn, W. Karesh, E. Bosi, M. Andau, S. Alsisto, Intake, utilization, and composition of browses consumed by the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis harissoni) in captivity in Sabah, Malaysia, in Zoo Biology, vol. 25, n. 5, 2006, pp. 417–431, DOI:10.1002/zoo.20107.

- ^ a b c von Muggenthaler, Elizabeth, Paul Reinhart, Brad Limpany, and R. Barton Craft, Songlike vocalizations from the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), in Acoustics Research Letters Online, vol. 4, n. 3, 2003, p. 83, DOI:10.1121/1.1588271. URL consultato il 13 novembre 2007.

- ^ a b Z. Zainal Zahari, Y. Rosnina, H. Wahid, K.c. Yap, and M.R. Jainudeen, Reproductive behaviour of captive Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), in Animal Reproduction Science, vol. 85, n. 3-4, 2005, pp. 327–335, DOI:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.041.

- ^ Z. Zainal-Zahari, Y. Rosnina, H. Wahid, and M. R. Jainudeen, Gross Anatomy and Ultrasonographic Images of the Reproductive System of the Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), in Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia: Journal of Veterinary Medicine Series C, vol. 31, n. 6, 2002, pp. 350–354, DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0264.2002.00416.x.

- ^ a b c T.L. Roth, R.W. Radcliffem, and N.J. van Strien, New hope for Sumatran rhino conservation (abridged from Communique), in International Zoo News, vol. 53, n. 6, 2006, pp. 352–353.

- ^ T.L. Roth, J.K. O'Brien, M.A. McRae, A.C. Bellem, S.J. Romo, J.L. Kroll and J.L. Brown, Ultrasound and endocrine evaluation of the ovarian cycle and early pregnancy in the Sumatran rhinoceros, Dicerorhinus sumatrensis, in Reproduction, vol. 121, n. 1, 2001, pp. 139–149, DOI:10.1530/rep.0.1210139.

- ^ a b Roth, T.L., Breeding the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) in captivity: behavioral challenges, hormonal solutions, in Hormones and Behavior, vol. 44, 2003, p. 31.

- ^ Rabinowitz, Alan, Helping a Species Go Extinct: The Sumatran Rhino in Borneo, in Conservation Biology, vol. 9, n. 3, 1995, pp. 482–488, DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1995.09030482.x.

- ^ a b Nico J. van Strien, Conservation Programs for Sumatran and Javan Rhino in Indonesia and Malaysia, in Proceedings of the International Elephant and Rhino Research Symposium, Vienna, June 7–11, 2001, Scientific Progress Reports, 2001.

- ^ Andalas - A Living Legacy, in Cincinnati Zoo. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007 (archiviato dall'url originale il November 17, 2007).

- ^ It's a Girl! Cincinnati Zoo's Sumatran Rhino Makes History with Second Calf, in Cincinnati Zoo. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ Meet "Harry" the Sumatran Rhino!, in Cincinnati Zoo. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007 (archiviato dall'url originale il November 17, 2007).

- ^ Watson, Paul, A Sumatran rhino's last chance for love, in The Los Angeles Times, April 26, 2007. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ The Littlest Rhino, in Asia Geographic. URL consultato il 6 dicembre 2007.

- ^ The Forgotten Rhino, in NHNZ. URL consultato il 6 dicembre 2007.

- ^ Rhinos alive and well in the final frontier, in New Straits Times (Malaysia), July 2, 2006.

- ^ Rhino on camera was rare sub-species: wildlife group, in Agence France Presse, April 25, 2007.

- ^ Video of the Sumatran Rhinoceros is available on the World Wildlife Fund web site.

External links

- Wikimedia Commons contiene immagini o altri file su Panjabi/Prove