- Tetragrammaton redirects here. For other meanings see Tetragrammaton (disambiguation).

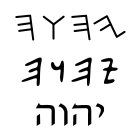

Yahweh is an English reading of Template:Hebrew (the Tetragrammaton "(the word) of four letters", from Greek tetra- "four" + gramma (genitive: grammatos) "letter, something written"[1]), the name of God in the Bible, as preserved in the original consonantal Hebrew Bible text. This form of God's name is used in modern Bible translations and literature during the last two centuries.

The four Hebrew consonants read JHWH (in German-originated transliteration) or YHWH. It is also common to use YHVH and JHVH.

Historical overview

During the Babylonian captivity, the Hebrew language spoken by the Jews was replaced by the Aramaic language of their Babylonian captors, which was closely related to Hebrew and, while sharing many vocabulary words in common, contained some words that sounded the same or similar but had other meanings. In Aramaic, the Hebrew word for “blaspheme” used in Leviticus 24:16, “Anyone who blasphemes the name of YHWH must be put to death” carried the meaning of “pronounce” rather than “blaspheme”. When the Jews began speaking Aramaic, this verse was understood to mean, “Anyone who pronounces the name of YHWH must be put to death.” Since then, Jews have maintained the custom of not pronouncing the name, but use Adonai (“my Lord [plural of majesty]”) instead. During the first few centuries AD this may have resulted in loss of traditional memory of how to pronounce the Name (except among Samaritans).

When Hebrew no longer was a living language, the Masoretes added vowel points to the consonant text to assist readers. To Template:Hebrew they usually added the vowels for "Adonai", the word to use when reading the Bible text.

Many Jews will not even use "Adonai" except when praying, and substitute other terms, e.g. HaShem ("The Name") or the nonsense word Ado-Shem, out of fear of the potential misuse of the divine name. In written English, "G-d" is a common substitute.

Parts of the Talmud, particularly those dealing with Yom Kippur, seem to imply that the Tetragrammaton should be pronounced in several ways, with only one (not explained in the text, and apparently kept by oral tradition by the Kohen Gadol) being the personal name of God.

In late Kabbalistic works, the term HWYH - הוי' (pronounced Havayeh) is used.

Translators often render YHWH as a word meaning "Lord", e.g. Greek Κυριος, Latin Dominus, and following that, English "the Lord", Polish Pan, Welsh Arglwydd, etc.

Because the name was no longer pronounced and its own vowels were not written, its own pronunciation was forgotten. When Christians, unaware of the Jewish tradition, started to read the Hebrew Bible, they read Template:Hebrew as written with YHWH's consonants with Adonai's vowels, and thus said or transcribed Iehovah. Today this transcription is generally recognized as mistaken. See the page Jehovah for more information.

The Sacred Name Movement

A movement began growing in the sixties in modern theology to restore the Sacred Name to almost 7000 instances where it appears in the Bible[2]. This movement continues today and is known as the Sacred Name Movement.

Pronunciation of the Name

Various proposals exist for what the vowels of Template:Hebrew were. Current convention is Template:Hebrew, that is, "Yahweh" (IPA: /'jahwe/). Evidence is:

- Some Biblical theophoric names end in -ia(h) or -yahu as shortened forms of YHWH: that points to the first vowel being "a".

- Various Early Christian Greek transcriptions of the Hebrew Divine Name seem to point to "Yahweh" or similar.

- Samaritan priests have preserved a liturgical pronunciation "Yahwe" or "Yahwa" to the present day [3].

Today many scholars accept this proposal[4], based on the pronunciation conserved both by the Church Fathers (as noted above) and by the Samaritans[5]. (Here 'accept' does not necessarily mean that they actually believe that it describes the truth, but rather that among the many vocalizations that have been proposed, none is clearly superior. That is, 'Yahweh' is the scholarly convention, rather than the scholarly consensus.)

Evidence from theophoric names

"Yahū" or "Yehū" is a common short form for "Yahweh" in Hebrew theophoric names; as a prefix it sometimes appears as "Yehō-". This has caused two opinions:

- In former times (at least from c.1650 AD), that it was abbreviated from the supposed pronunciation "Yehowah", rather than "Yahweh" which contains no 'o'- or 'u'-type vowel sound in the middle.

- [2] Recently, that, as "Yahweh" is likely an imperfective verb form, "Yahu" is its corresponding preterite or jussive short form: compare yiŝtahaweh (imperfective), yiŝtáhû (preterit or jussive short form) = "do obeisance".

George Wesley Buchanan in Biblical Archaeology Review argues for (1), as the prefix "Yehu-" or "Yeho-" always keeps its second vowel. [6]

Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible Section # 2.1 supports (1) for the same reason.

The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon (1848)[7] in its article הוה supports (1) because of the "Yeho-" name prefixes and the vowel pointing difference described in #Details of vowel pointing.

Smith’s 1863 A Dictionary of the Bible says that "Yahweh" is possible because shortening to "Yahw" would end up as "Yahu" or similar.

The Jewish Encyclopedia of 1901-1906 in the Article:Names Of God has a very similar discussion, and also gives the form Jo or Yo (Template:Hebrew) contracted from Jeho or Yeho (Template:Hebrew).

The Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1910-11, vol. 15, pp. 312, in its article "JEHOVAH", also says that "Jelo-" or "Jo" can be explained from "Yahweh", and that the suffix "-jah" can be explained fom "Yahweh" better than from "Yehowah".

Chapter 1 of The Tetragrammaton and the Christian Greek Scriptures, under the heading: THE PRONUNCIATION OF GOD'S NAME quotes from Insight on the Scriptures, Volume 2, page 7:

- Hebrew Scholars generally favor "Yahweh" as the most likely pronunciation. They point out that the abbreviated form of the name is Yah (Jah in the Latinized form), as at Psalm 89:8 and in the expression Hallelu-Yah (meaning "Praise Yah, you people!") (Ps 104:35; 150:1,6). Also, the forms Yehoh', Yoh, Yah, and Ya'hu, found in the Hebrew spelling of the names of Jehoshaphat, Joshaphat, Shephatiah, and others, can all be derived from Yahweh. ... Still, there is by no means unanimity among scholars on the subject, some favoring yet other pronunciations, such as "Yahuwa", "Yahuah", or "Yehuah".

Everett Fox in his introduction to his translation of The Five Books of Moses stated: "Both old and new attempts to recover the ‘correct’ pronunciation of the Hebrew name [of God] have not succeeded; neither the sometimes-heard ‘Jehovah’ nor the standard scholarly ‘Yahweh’ can be conclusively proven."

Using consonants as semi-vowels

In ancient Hebrew, the [[Hebrew alphabet#Numerical value and pronunciation|letter Template:Hebrew]], known to modern Hebrew speakers as vav, was a semivowel /w/ (as in English, not as in German) rather than a letter v[8]. The letter is referred to as waw in the academic world. Because the ancient pronunciation differs from the modern pronunciation, it is common today to represent Template:Hebrew as YHWH rather than YHVH.

In Biblical Hebrew, most vowels are not written and the rest are written only ambiguously, as the vowel letters double as consonants (similar to the Latin use of V to indicate both U and V). See Matres lectionis for details. For similar reasons, an appearance of the Tetragrammaton in ancient Egyptian records of the 13th century BC sheds no light on the original pronunciation. [9] Therefore it is, in general, difficult to deduce how a word is pronounced from its spelling only, and the Tetragrammaton is a particular example: two of its letters can serve as vowels, and two are vocalic place-holders, which are not pronounced.

This difficulty occurs somewhat also in Greek when transcribing Hebrew words, because of Greek's lack of a letter for consonant 'y' and (since loss of the digamma) of a letter for "w", forcing the Hebrew consonants yod and waw to be transcribed into Greek as vowels. Also, non-initial 'h' caused difficulty for Greeks and was liable to be omitted; х (chi) was pronounced as 'k' + 'h' (as in modern Hindi "lakh") and could not be used to spell 'h' as in e.g. Modern Greek Χάρρι = "Harry".

J/Y

The English practice of transcribing Biblical Hebrew yod as "j" and pronouncing it "dzh" (/dʒ/) started when in late Latin the pronunciation of consonantal "i" changed from "y" to "dzh" but continued to be spelled "i", bringing along with it Latin transcriptions and spoken renderings of Biblical and other foreign words and names. To avoid confusion it is easiest to transcribe Hebrew yod as "y" in English.

Kethib and Qere and Qere perpetuum

The original consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible was provided with vowel marks by the Masoretes to assist reading. In places where the consonants of the text to be read (the Qere) differed from the consonants of the written text (the Kethib), they wrote the Qere in the margin as a note showing what was to be read. In such a case the vowels of the Qere were written on the Kethib. For a few very frequent words the marginal note was omitted: this is called Q're perpetuum.

One of these frequent cases was God's name, that should not be pronounced, but read as "adonai" ("My Lord [plural of majesty]"), or, if the previous or next word already was "adonai", or "adoni" ("My Lord"), as "elohim" ("God"). This combination produces Template:Hebrew and Template:Hebrew respectively, non-words that would spell "yehovah" and "yehovih" respectively.

The oldest manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, such as the Aleppo Codex and the Codex Leningradensis mostly write Template:Hebrew (yehvah), with no pointing on the first H; this points to its Qere being 'Shema', which is Aramaic for "the Name".

Gerard Gertoux wrote that in the Leningrad Codex of 1008-1010, the Masoretes used 7 different vowel pointings [i.e. 7 different Q're's] for YHWH. [10]

Jehovah

Later, Christian Europeans who did not know about the Q're perpetuum custom took these spellings at face value, producing the form "Jehovah" and spelling variants of it. For more information, see the page Jehovah.

Counts

According to the Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon p, Template:Hebrew (Qr Template:Hebrew) occurs 6518 times, and Template:Hebrew (Qr Template:Hebrew) occurs 305 times in the Masoretic Text.

It appears 6,823 times in the Jewish Bible, according to the Jewish Encyclopedia, and 6,828 times each in the Biblia Hebraica and Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia texts of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The vocalizations of יְהֹוָה and אֲדֹנָי are not identical

The "simple shewa" (schwa vowel, usually written as 'e') in Yehovah and the "hatef patah" (short a) in Adonay are not identical. Two reasons have been suggested for this:

- A spelling "Yahovah" causes a risk that a reader might start reading "Yah", which is a form of the Name, and the first half of the full Name.

- The two are not really different: both short vowels, shva and hatef-patah, were allophones of the same phoneme used in different situations. Adonai uses the "hatef patah" because of the glottal nature of its first consonant aleph (the glottal stop), but the first consonant of YHWH is yod, which is not glottal, and so uses the vowel shva.

Evidence from very old scrolls

The discovery of the Qumran scrolls has added support to some parts of this position. These scrolls are unvocalized, showing that the position of those who claim that the vowel marks were already written by the original authors of the text is untenable. Many of these scrolls write (only) the tetragrammaton in paleo-Hebrew script, showing that the Name was treated specially. See also this link.

As said above, the Aleppo and Leningrad codices do not use the holem (o) in their vocalization, or only in very few instances, so that the (systematic) spelling "Yehovah" is more recent than about 1000 A.D. or from a different tradition.

Original pronunciation

The main approaches in modern attempts to determine a pronunciation of YHWH have been study of the Hebrew Bible text, study of theophoric names, and study of early Christian Greek texts that contain reports about the pronunciation. Evidence from Semitic philology and archeology has been tried.

The result is a "scholarly convention to pronounce YHWH as Yahweh".

Delitzsch prefers "Template:Hebrew" (yahavah) since he considered the shwa quiescens below Template:Hebrew ungrammatical.

In his 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible", William Smith prefers the form "Template:Hebrew" (yahaveh). Many other variations have been proposed.

However, Gesenius' proposal gradually became accepted as the best scholarly reconstructed vocalized Hebrew spelling of the Tetragrammaton.

Early Greek and Latin forms

The writings of the Church Fathers contain several references to God's name in Greek or Latin. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia (1907) and [11].

| author & work | Greek/Latin | notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diodorus Siculus (I, 94) | Ἰαῶ | ia-o | |

| Irenaeus ("Against Heresies", II, xxxv, 3, in P. G., VII, col. 840) | Ἰαωθ | iaoth | the Gnostics formed a compound with the last syllable of Sabaoth |

| Irenaeus ("Against Heresies", I, iv, 1, in P.G., VII, col. 481) | Ἰαῶ | ia-o | Valentinian heretics' form |

| Origen ("In Joh.", II, 1, in P.G., XIV, col. 105) | Ἰαο | ia-o | |

| Porphyry (Eusebius, "Praep. evang", I, ix, 21, in P.G., XXI, col. 72) | Ἰευώ | ieuo | |

| Pseudo-Jerome ("Breviarium in Psalmos", in P.L., XXVI, 828) | iaho | "tetragrammaton legi potest iaho" | |

| Clement of Alexandria "Stromata", V, 6, [ Variants: Ἰὰοὐέ, Ἰαουαι; cod. L. Ἰαού ] [3] ( Ἰαού is found in the 11th century Greek Codex L., which is the sole authority for the Stromateis.) | Ἰαού | iaou | Scroll down to page 317 of [4], or see [5] for additional information on the 11th century Greek Codex L. [e.g. Codex Laurentianus V 3] |

| Clement of Alexandria "Stromata", V, 6, [ Variants: Ἰὰοὐέ, Ἰαουαι; cod. L. Ἰαού ] [6] ( Ἰαού is found in Migne's 19th century Patrologia Graeca, IX, col. 60. ) | Ἰαού | iaou | |

| In 1863 Ἰὰοὐέ could be found in a catena to the Pentateuch in a MS. at Turin. | Ἰὰ οὐέ | ia oue | Refer to Smith's 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible" [7] |

| Clement of Alexandria "Stromata", V, 6, [ Variants: Ἰὰοὐέ, Ἰαουαι; cod. L. Ἰαού ] [8] (Editors of 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica say that Iaoue is found in writings of Clement of Alexandria) ( Ἰὰοὐέ is found in 1960 and 1981 critical editions of the writings of Clement of Alexandria) | Ἰὰ οὐέ | ia oue | Clement wrote that it means "Who is, and who shall be". [9] [10] |

| Clement of Alexandria "Stromata", V, 6, [Variants: Ἰὰοὐέ, Ἰαουαι; cod. L. Ἰαού ] [11] ( Ἰαουαι is found in some MSS ) | Ἰα ουαι | Ia ouai | The New Catholic Encyclopedia of 1967 lists Ἰαουαι as evidence that YHWH is pronounced "Yahweh" |

| Epiphanius ("Against Heresies", I, iii, 40, in P.G., XLI, col. 685) | Ἰαβέ | iabé | |

| Theodoret, "Ex. quaest.", xv, in P. G., LXXX, col. 244 | Ἰαβέ, Ἰαβαι |

iabé, iabai |

"Samaritan form" |

| Theodoret, "Ex. quaest.", xv, in P. G., LXXX, col. 244 | Ἀϊά | Aia | "Jewish form" |

| James of Edessa ref. Lamy, "La science catholique", 1891, p. 196 | Jehjeh | ||

| Epiphanius ("Against Heresies", I, iii, 40, in P.G., XLI, col. 685) | Ἰα | ia | |

| Jerome, "Ep. xxv ad Marcell.", in P. L., XXII, col. 429 | says some ignorant Greek writers copied יהוה as ΠΙΠΙ (= πιπι) | ||

Josephus

Josephus in Jewish Wars, chapter V, verse 235, wrote "τὰ ἱερὰ γράμματα· ταῦτα δ' ἐστὶ φωνήεντα τέσσαρα" ("...[engraved with] the holy letters; and they are four vowels"), presumably because Hebrew yod and waw, even if consonantal, would have to be transcribed into the Greek of the time as vowels.

Clement of Alexandria

As noted above, the various manuscripts of Clement's Stromata are reported to have different forms in Stromata V,6:34-35. The text of the 11th century Greek Codex Laurentianus [12] has "ιαου". A catena referred to by A. le Boulluec [13] ("Coisl. 113 fol. 368v") and by Smith’s 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible" ("a catena to the Pentateuch in a MS. at Turin") is reported to have "ια ουε". The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica [14] reports "Variants: Iα ουε, Iα ουαι; cod. L. Iαου". [12]

The translation of Clement's Stromata in Volume II of the classic Ante-Nicene Fathers series, says:

- "Further, the mystic name of four letters which was affixed to those alone to whom the adytum was accessible, is called Jave, which is interpreted, 'Who is and shall be.' The name of God, too, among the Greeks contains four letters."[15]

Magic papyri

Spellings of the Tetragrammaton occur among the many combinations and permutations of names of powerful agents that occur in Egyptian magical writings[16]. One of these forms is the heptagram ιαωουηε[17]. See also http://www.sacred-texts.com/gno/gar/gar43.htm .

In the magical texts, Iave (Jahveh Sebaoth), and Iαβα, occurs frequently. [18] In an Ethiopic list of magical names of Jesus, purporting to have been taught by him to his disciples, Yawe[19] [20] is found.

Gesenius proposes that YHWH should be punctuated as Template:Hebrew = Yahweh

In the early 19th century Hebrew scholars were still critiquing "Jehovah" [a.k.a. Iehovah and Iehouah] because they believed that the vowel points of Template:Hebrew were not the actual vowel points of God's name. The Hebrew scholar Wilhelm Gesenius [1786-1842] had suggested that the Hebrew punctuation Template:Hebrew, which is transliterated into English as "Yahweh", might more accurately represent the actual pronunciation of God's name than the Biblical Hebrew punctuation "Template:Hebrew" [ from which the English name Jehovah has been derived ] does.

Wilhelm Gesenius is noted for being one of the greatest Hebrew and biblical scholars [13]. His proposal to read YHWH as "Template:Hebrew" (see image to the right) was based in large part on various Greek transcriptions, such as ιαβε, dating from the first centuries AD, but also on the forms of theophoric names.

- In his Hebrew Dictionary Gesenius (see image of German text) supports the pronunciation "Yahweh" because of the Samaritan pronunciation Ιαβε reported by Theodoret, and that the theophoric name prefixes YHW [Yeho] and YH [Yo] can be explained from the form "Yahweh".

- Today many scholars accept Gesenius's proposal to read YHWH as Template:Hebrew.

- (Here 'accept' does not necessarily mean that they actually believe that it describes the truth, but rather that among the many vocalizations that have been proposed, none is clearly superior. That is, 'Yahweh' is the scholarly convention, rather than the scholarly consensus.)

Inferences

Various people draw various conclusions from this Greek material.

William Smith writes in his 1863 "A Dictionary of the Bible" about the different Hebrew forms supported by these Greek forms:

- ... The votes of others are divided between Template:Hebrew (yahveh) or Template:Hebrew (yahaveh), supposed to be represented by the Ιαβέ of Epiphanius mentioned above, and Template:Hebrew (yahvah) or Template:Hebrew (yahavah), which Fürst holds to be the Ιευώ of Porphyry, or the Ιαού of Clemens Alexandrinus.

The editors of The New Bible Dictionary (1962) write:

- The pronunciation Yahweh is indicated by transliterations of the name into Greek in early Christian literature, in the form Ιαουε (Clement of Alexandria) or Ιαβε (Theodoret; by this time β had the pronunciation of v).

As already mentioned, Gesenius arrived at his form using the evidence of proper names, and following the Samaritan pronunciation Ιαβε reported by Theodoret.

Usage of YHWH

In ancient Judaism

Several centuries before the Christian era the name YHWH had ceased to be commonly used by the Jews. Some of the later writers in the Old Testament employ the appellative Elohim, God, prevailingly or exclusively: a collection of Psalms (Ps. xlii.-lxxxiii.) was revised by an editor who changed the Yhwh of the authors into Elohim (see e.g. xlv. 7; xlviii. 10; l. 7; li. 14); observe also the frequency of the Most High, the God of Heaven, King of Heaven, in Daniel, and of Heaven in First Maccabees.

The oldest complete Septuagint (Greek Old Testament) versions, from around the second century A.D., consistently use Κυριος (= "Lord"), where the Hebrew has YHWH, corresponding to substituting Adonay for YHWH in reading the original; in books written in Greek in this period (e.g. Wisdom, 2 and 3 Maccabees), as in the New Testament, Κυριος takes the place of the name of God. However, older fragments contain the name YHWH. [21] In the P. Ryl. 458 (perhaps the oldest extant Septuagint manuscript) there are blank spaces ,leading some scholars to believe that the Tetragrammaton must have been written where these breaks or blank spaces are.[22]

Josephus, who as a priest knew the pronunciation of the name, declares that religion forbids him to divulge it.

Philo calls it ineffable, and says that it is lawful for those only whose ears and tongues are purified by wisdom to hear and utter it in a holy place (that is, for priests in the Temple); and in another passage, commenting on Lev. xxiv. 15 seq.: "If any one, I do not say should blaspheme against the Lord of men and gods, but should even dare to utter his name unseasonably, let him expect the penalty of death." [23]

Various motives may have concurred to bring about the suppression of the name:

- An instinctive feeling that a proper name for God implicitly recognizes the existence of other gods may have had some influence; reverence and the fear lest the holy name should be profaned among the heathen.

- Desire to prevent abuse of the name in magic. If so, the secrecy had the opposite effect; the name of the god of the Jews was one of the great names, in magic, heathen as well as Jewish, and miraculous efficacy was attributed to the mere utterance of it.

- Avoiding risk of the Name being used as an angry expletive, as reported in Leviticus 24:11 in the Bible.

In the liturgy of the Temple the name was pronounced in the priestly benediction (Num. vi. 27) after the regular daily sacrifice (in the synagogues a substitute— probably Adonai— was employed);[24] on the Day of Atonement the High Priest uttered the name ten times in his prayers and benediction.

In the last generations before the fall of Jerusalem, however, it was pronounced in a low tone so that the sounds were lost in the chant of the priests.[25]

In later Judaism

After the destruction of the Temple (A.D. 70) the liturgical use of the name ceased, but the tradition was perpetuated in the schools of the rabbis.[26] It was certainly known in Babylonia in the latter part of the 4th century,[27] and not improbably much later. Nor was the knowledge confined to these pious circles; the name continued to be employed by healers, exorcists and magicians, and has been preserved in many places in magical papyri.

The vehemence with which the utterance of the name is denounced in the Mishna—He who pronounces the Name with its own letters has no part in the world to come!.[28] —suggests that this misuse of the name was not uncommon among Jews.

Among the Samaritans

The Samaritans, who otherwise shared the scruples of the Jews about the utterance of the name, seem to have used it in judicial oaths to the scandal of the rabbis. [29] (Their priests have preserved a liturgical pronunciation "Yahwe" or "Yahwa" to the present day [30].)

Modern

The Jerusalem Bible (1966) uses "Yahweh" exclusively.

Short forms

"Yahū" or "Yehū" is a common short form for "Yahweh" in Hebrew theophoric names; as a prefix it sometimes appears as "Yehō-". In former times that was thought to be abbreviated from the supposed pronunciation "Yehowah". There is nowadays an opinion [14] that, as "Yahweh" is likely an imperfective verb form, "Yahu" is its corresponding preterite or jussive short form: compare yiŝtahaweh (imperfective), yiŝtáhû (preterit or jussive short form) = "do obeisance".

In some places, such Exodus 15:2, the name YHWH is shortened to Template:Hebrew (Yah). This same syllable is found in Hallelu-yah. Here the ה has mappiq, i.e., is consonantal, not a mater lectionis.

It is often assumed that this is also the second element -ya of the Aramaic "Marya": the Peshitta Old Testament translates Adonai with "Mar" (Lord), and YHWH with "Marya".

Derivation

Putative etymology

Jahveh or Yahweh is apparently an example of a common type of Hebrew proper names which have the form of the 3rd pers. sing. of the verb. e.g. Jabneh (name of a city), Jabin, Jamlek, Jiptal (Jephthah), &c. Most of these really are verbs, the suppressed or implicit subject being 'el, "numen, god", or the name of a god; cf. Jabneh and Jabne-el, Jiptah and Jiptah-el.

The ancient explanations of the name proceed from Exod. iii. 14, 15, where "Yahweh[31] hath sent me" in v 15 corresponds to "Ehyeh hath sent me" in v. 14, thus seeming to connect the name Yahweh with the Hebrew verb hayah, "to become, to be". The Jewish interpreters found in this the promise that God would be with his people (cf. v. 12) in future oppressions as he was in the present distress, or the assertion of his eternity, or eternal constancy; the Alexandrian translation 'Eγω ειμι ο ων. . . ' O ων απεσταλκεν με προς υμας understands it in the more metaphysical sense of God's absolute being. Both interpretations, "He (who) is (always the same);" and , "He (who) is (absolutely the truly existent);" import into the name all that they profess to find in it; the one, the religious faith in God's unchanging fidelity to his people, the other, a philosophical conception of absolute being which is foreign both to the meaning of the Hebrew verb and to the force of the tense employed.

Modern scholars have sometimes found in the name the expression of the aseity[32] of God; sometimes of his reality in contrast to the imaginary gods of the heathen.

Another explanation, which appears first in Jewish authors of the middle ages and has found wide acceptance in recent times, derives the name from the causative of the verb; He (who) causes things to be, gives them being; or calls events into existence, brings them to pass; with many individual modifications of interpretation—creator, life giver, fulfiller of promises. A serious objection to this theory in every form is that the verb hayah, "to be" has no causative stem in Hebrew; to express the ideas which these scholars find in the name Yahweh the language employs altogether different verbs.

Another tradition regards the name as coming from three verb forms sharing the same root YWH, the words HYH haya Template:Hebrew: "He was"; HWH howê Template:Hebrew: "He is"; and YHYH yihiyê Template:Hebrew: "He will be". This is supposed to show that God is timeless, as some have translated the name as "The Eternal One". Other interpretations include the name as meaning "I am the One Who Is." This can be seen in the traditional Jewish account of the "burning bush" commanding Moses to tell the sons of Israel that "I AM (Template:Hebrew) has sent you." (Exodus 3:13-14) Some suggest: "I AM the One I AM" Template:Hebrew, or "I AM whatever I need to become". This may also fit the interpretation as "He Causes to Become." Many scholars believe that the most proper meaning may be "He Brings Into Existence Whatever Exists" or "He who causes to exist". Young's Analytical Concordance to the Bible, which is based on the King James Version, says that the term "Jehovah" means "The Existing One."

Spinoza, in his Theologico-Political Treatise (Chap.2) asserts the derivation of "Jahweh" from "Being", writing that, "Moses conceived the Deity as a Being Who has always existed, does exist, and always will exist, and for this cause he calls Him by the name Jehovah, which in Hebrew signifies these three phases of existence." Following Spinoza, Constantin Brunner translates the Shema (Deut. 2-4) as, "Hear, O Israel, Being is our God, Being is One."

This assumption that Yahweh is derived from the verb "to be", as seems to be implied in Exod. iii. 14 seq., is not, however, free from difficulty. "To be" in the Hebrew of the Old Testament is not hawah, as the derivation would require, but hayah; and we are thus driven to the further assumption that hawah belongs to an earlier stage of the language, or to some older speech of the forefathers of the Israelites.

This hypothesis is not intrinsically improbable (and in Aramaic, a language closely related to Hebrew, "to be" is hawa); in adopting it we admit that, using the name Hebrew in the historical sense, Yahweh is not a Hebrew name. And, inasmuch as nowhere in the Old Testament, outside of Exod. iii., is there the slightest indication that the Israelites connected the name of their God with the idea of "being" in any sense, it may fairly be questioned whether, if the author of Exod. 14 seq., intended to give an etymological interpretation of the name Yahweh,[33] his etymology is any better than many other paronomastic explanations of proper names in the Old Testament, or than, say, the connection of the name Aπολλων (Apollo) with απολουων, απολυων in Plato's Cratylus, or popular derivations from απολλυμι = "I lose (transitive)" or "I destroy".

"I am"

Mishearings and misunderstandings of this explanation has led to a popular idea that "Yahweh" means "I am", resulting in God, and by colloquial extension sometimes anything which is very dominant in its area [15], being called "the great I AM".

From a verb meaning "destroy" or similar?

A root hawah is represented in Hebrew by the nouns howah (Ezek., Isa. xlvii. II) and hawwah (Ps., Prov., Job) "disaster, calamity, ruin."[34] The primary meaning is probably "sink down, fall", in which sense (common in Arabic) the verb appears in Job xxxvii. 6 (of snow falling to earth).

A Catholic commentator of the 16th century, Hieronymus ab Oleastro, seems to have been the first to connect the name "Jehova" with "howah" interpreting it as "contritio sive pernicies" (destruction of the Egyptians and Canaanites); Daumer, adopting the same etymology, took it in a more general sense: Yahweh, as well as Shaddai, meant "Destroyer", and fitly expressed the nature of the terrible god who he identified with Moloch.

The derivation of Yahweh from hawah is formally unimpeachable, and is adopted by many recent scholars, who proceed, however, from the primary sense of the root rather than from the specific meaning of the nouns. The name is accordingly interpreted, He (who) falls (baetyl, βαιτυλος, meteorite); or causes (rain or lightning) to fall (storm god); or casts down (his foes, by his thunderbolts). It is obvious that if the derivation be correct, the significance of the name, which in itself denotes only "He falls" or "He fells", must be learned, if at all, from early Israelitish conceptions of the nature of Yahweh rather than from etymology.

Cultus

A more fundamental question is whether the name Yahweh originated among the Israelites or was adopted by them from some other people and speech.[35]

The biblical author of the history of the sacred institutions (P) expressly declares that the name Yahweh was unknown to the patriarchs (Exod. vi. 3), and the much older Israelite historian (E) records the first revelation of the name to Moses (Exod. iii. 13-15), apparently following a tradition according to which the Israelites had not been worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses, or, as he conceived it, had not worshipped the god of their fathers under that name.

The revelation of the name to Moses was made at a mountain sacred to Yahweh, (the mountain of God) far to the south of Canaan, in a region where the forefathers of the Israelites had never roamed, and in the territory of other tribes; and long after the settlement in Canaan this region continued to be regarded as the abode of Yahweh (Judg. v. 4; Deut. xxxiii. 2 sqq.; I Kings xix. 8 sqq. &c).

Moses is closely connected with the tribes in the vicinity of the holy mountain; according to one account, he married a daughter of the priest of Midian (Exod. ii. 16 sqq.; iii. 1); to this mountain he led the Israelites after their deliverance from Egypt; there his father-in-law met him, and extolling Yahweh as greater than all the gods, offered (in his capacity as priest of the place?) sacrifices, at which the chief men of the Israelites were his guests; there the religion of Yahweh was revealed through Moses, and the Israelites pledged themselves to serve God according to its prescriptions.

It appears, therefore, that in the tradition followed by the Israelite historian the tribes within whose pasture lands the mountain of God stood were worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses; and the surmise that the name Yahweh belongs to their speech, rather than to that of Israel, has considerable probability.

One of these tribes was Midian, in whose land the mountain of God lay. The Kenites also, with whom another tradition connects Moses, seem to have been worshippers of Yahweh.

It is probable that Yahweh was at one time worshipped by various tribes south of Palestine, and that several places in that wide territory (Horeb, Sinai, Kadesh, &c.) were sacred to him; the oldest and most famous of these, the mountain of God, seems to have lain in Arabia, east of the Red Sea. From some of these peoples and at one of these holy places, a group of Israelite tribes adopted the religion of Yahweh, the God who, by the hand of Moses, had delivered them from Egypt.[36]

The tribes of this region probably belonged to some branch of the Arabian desert Semitic stock, and the name Yahweh has, accordingly, been connected with the Arabic hawa, the void (between heaven and earth), "the atmosphere, or with the verb hawa, cognate with Heb. hawah, "sink, glide down (through space)"; hawwa "blow (wind)". "He rides through the air, He blows" (Wellhausen), would be a fit name for a god of wind and storm. There is, however, no certain evidence that the Israelites in historical times had any consciousness of the primitive significance of the name. (what is the source for this assertion?)

However, the 'h' in the root h-w-h, h-y-h = "be, become" and in "Yahweh" is the ordinary 'h' (He (letter)), and the 'h' in the roots ħ-y-w = "live" and ħ-w-glottalstop = "air, blow (of wind)" is the Semitic laryngeal 'h' (Heth (letter)) which is usually transcribed as 'h' with a dot under.

Yahu

According to one theory, Yahweh, or Yahu, Yaho,[37] is the name of a god worshipped throughout the whole, or a great part, of the area occupied by the Western Semites.

In its earlier form this opinion rested chiefly on certain misinterpreted testimonies in Greek authors about a god 'Iαω and was conclusively refuted by Baudissin; recent adherents of the theory build more largely on the occurrence in various parts of this territory of proper names of persons and places which they explain as compounds of Yahu or Yah.[38]

The explanation is in most cases simply an assumption of the point at issue; some of the names have been misread; others are undoubtedly the names of Jews.

There remain, however, some cases in which it is highly probable that names of non-Israelites are really compounded with Yahweh. The most conspicuous of these is the king of Hamath who in the inscriptions of Sargon (722-705 B.C.) is called Yaubi'di and Ilubi'di (compare Jehoiakim-Eliakim). Azriyau of Jaudi, also, in inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser (745-728 B.C.), who was formerly supposed to be Azariah (Uzziah) of Judah, is probably a king of the country in northern Syria known to us from the Zenjirli inscriptions as Ja'di.

Mesopotamian influence

Friedrich Delitzsch brought into notice three tablets, of the age of the first dynasty of Babylon, in which he read the names of Ya- a'-ve-ilu, Ya-ve-ilu, and Ya-u-um-ilu ("Yahweh is God"), and which he regarded as conclusive proof that Yahweh was known in Babylonia before 2000 B.C.; he was a god of the Semitic invaders in the second wave of migration, who were, according to Winckler and Delitzsch, of North Semitic stock (Canaanites, in the linguistic sense).[39]

We should thus have in the tablets evidence of the worship of Yahweh among the Western Semites at a time long before the rise of Israel. The reading of the names is, however, extremely uncertain, not to say improbable, and the far-reaching inferences drawn from them carry no conviction.

In a tablet attributed to the 14th century B.C. which Sellin found in the course of his excavations at Tell Ta'annuk (the city Taanach of the O.T.) a name occurs which may be read Ahi-Yawi (equivalent to Hebrew Ahijah);[40] if the reading be correct, this would show that Yahweh was worshipped in Central Palestine before the Israelite conquest.

The reading is, however, only one of several possibilities. The fact that the full form Yahweh appears, whereas in Hebrew proper names only the shorter Yahu and Yah occur, weighs somewhat against the interpretation, as it does against Delitzsch's reading of his tablets.

It would not be at all surprising if, in the great movements of populations and shifting of ascendancy which lie beyond our historical horizon, the worship of Yahweh should have been established in regions remote from those which it occupied in historical times; but nothing which we now know warrants the opinion that his worship was ever general among the Western Semites.

Many attempts have been made to trace the West Semitic Yahu back to Babylonia. Thus Delitzsch formerly derived the name from an Akkadian god, I or Ia; or from the Semitic nominative ending, Yau;[41] but this deity has since disappeared from the pantheon of Assyriologists. Bottero speculates that the West Semitic Yah/Ia, in fact is a version of the Babylonian God Ea, a view given support by the earliest finding of this name at Ebla during the reign of Ebrum, at which time the city was under Mesopotamian hegemony of Sargon of Akkad.

Attributes

Assuming that Yahweh was primitively a nature god, scholars in the 19th century discussed the question over what sphere of nature he originally presided. According to some, he was the god of consuming fire; others saw in him the bright sky, or the heaven; still others recognized in him a storm god, a theory with which the derivation of the name from Hebrew hawah or Arabic hawa well accords (see also Job chapters 37-38). The association of Yahweh with storm and fire is frequent in the Old Testament. The thunder is the voice of Yahweh, the lightning his arrows, and the rainbow his bow. The revelation at Sinai is amid the awe-inspiring phenomena of tempest. Yahweh leads Israel through the desert in a pillar of cloud and fire. He kindles Elijah's altar by lightning, and translates the prophet in a chariot of fire. See also Judg. v. 4 seq.. In this way, he seems to have usurped the attributes of the Canaanite god Baal Hadad. In Ugarit, the struggle between Baal and Yam, suggests that Baal's brother Ya'a was a water divinity - the god of Rivers (Nahar) and of the Sea (Yam).

Many religions today do not use the name Jehovah as much as they used to use it. The original Hebrew name Template:Hebrew appeared almost 7,000 times in the Old Testament, but is often replaced with "LORD" or "GOD" in popular Bibles. The Christian denomination that most commonly uses the name "Jehovah" is that of the Jehovah's Witnesses. They believe that God's personal name should not be over-shadowed by the above titles and often refer to Psalms 83:18 as a common place in most translations to find the name Jehovah still used in place of "LORD" and find justification for its use in Joel 2:32.

References

- ^ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?search=tetragrammaton

- ^ "Restoration of the Sacred Name," http://www.geocities.com/cherryhillrose/WhoisGod.html, October 5, 2002.

- ^ Footnote #11 from page 312 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica reads: "See Montgomery, Journal of Biblical Literature, xxv. (1906), 49-51."

- ^ Encycl. Britannica, 15th edition, 1994, passim.

- ^ Dio Uno E Trino, Piero Coda, Edizioni San Paolo s.r.l., 1993, pg 34.

- ^ [[Biblical Archaeology Review] 21.2 (March-April 1995), 31 George W. Buchanan, How God’s Name Was Pronounced

- ^ The Analytical Hebrew & Chaldee Lexicon by Benjamin Davidson ISBN 0913573035

- ^ (see any Hebrew grammar)

- ^ See pages 128 and 236 of the book "Who Were the Early Israelites?" by archeologist William G. Dever, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., Grand Rapids, MI, 2003.

- ^ refer to the table on page 144 of Gerard Gertoux's book: The Name of God Y.EH.OW.Ah which is pronounced as it is written I_EH_OU_AH.

- ^ B.D. Eerdmans, The Name Jahu, O.T.S. V (1948) 1-29.

- ^ Clement, Stromata, Migne's P.G., IX, col. 60.

- ^ Clément d'Alexandrie. Stromate V. Tome I: Introduction, texte critique et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Traduction de † P. Voulet, s. j.; Tome II : Commentaire, bibliographie et index, par A. Le Boulluec, Sources chrétiennes n° 278 et 279, Editions du Cerf, Paris 1981. (Tome I, pp. 80,81)

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1910-11, vol. 15, pp. 312, in the Article "JEHOVAH")

- ^ The Rev. Alexander Roberts, D.D, and James Donaldson, LL.D. (ed.). "VI. — The Mystic Meaning of the Tabernacle and Its Furniture". The Ante-Nicene Fathers, Vol. II: Fathers of the Second Century (American reprint of the Edinburgh edition ed.). p. 452. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ B. Alfrink, La prononciation 'Jehova' du tétragramme, O.T.S. V (1948) 43-62.

- ^ K. Preisendanz, Papyri Graecae Magicae, Leipzig-Berlin, I, 1928 and II, 1931

- ^ Footnote #9 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Deissmann, Bibelstudien, 13 sqq."

- ^ Footnote #10 from Page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Driver, Studia Biblica, I. 20."

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th edition (New York: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc., 1910-11), vol. 15, pp. 312, in the Article “JEHOVAH”

- ^ The New International Dictionary of New Testament Theology Volume 2, page 512

- ^ Paul Kahle, The Cairo Geniza (Oxford:Basil Blackwell,1959) p. 222

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See Josephus, Ant. ii. 12, 4; Philo, Vita Mosis, iii. II (ii. 114, ed. Cohn and Wendland); ib. iii. 27 (ii. 206). The Palestinian authorities more correctly interpreted Lev. xxiv. 15 seq., not of the mere utterance of the name, but of the use of the name of God in blaspheming God."

- ^ Footnote #4 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Siphre, Num. f 39, 43; M. Sotak, iii. 7; Sotah, 38a. The tradition that the utterance of the name in the daily benedictions ceased with the death of Simeon the Just, two centuries or more before the Christian era, perhaps arose from a misunderstanding of Menahoth, 109b; in any case it cannot stand against the testimony of older and more authoritative texts.

- ^ Footnote #5 from page 311 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Yoma, 39b; Jer. Yoma, iii. 7; Kiddushin, 71a."

- ^ Footnote #1 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"R. Johannan (second half of the 3rd century), Kiddushin, 71a."

- ^ Footnote #2 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:"Kiddushin, l.c. = Pesahim, 50a"

- ^ Footnote #3 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "M. Sanhedrin, x.I; Abba Saul, end of 2nd century."

- ^ Footnote #4 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads:Jer. Sanhedrin, x.I; R. Mana, 4th century.

- ^ Footnote #11 from page 312 of the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica reads: "See Montgomery, Journal of Biblical Literature, xxv. (1906), 49-51."

- ^ Footnote #13 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "This transcription will be used henceforth."

- ^ Footnote #14 from Page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "A-se-itas, a scholastic Latin expression for the quality of existing by oneself.

- ^ Footnote #15 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "The critical difficulties of these verses need not be discussed here. See W.R. Arnold, "The Divine Name in Exodus iii. 14," Journal of Biblical Literature, XXIV. (1905), 107-165."

- ^ Footnote #16 from page 312 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Cf. also hawwah, "desire", Mic. vii. 3; Prov. x. 3."

- ^ Footnote #1 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See HEBREW RELIGION"

- ^ Footnote #2 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "The divergent Judaean tradition, according to which the forefathers had worshipped Yahweh from time immemorial, may indicate that Judah and the kindred clans had in fact been worshippers of Yahweh before the time of Moses."

- ^ Footnote #3 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "The form Yahu, or Yaho, occurs not only in composition, but by itself; see Aramaic Papyri discovered at Assaan, B 4,6,II; E 14; J 6. This doubtless is the original of 'Iαω, frequently found in Greek authors and in magical texts as the name of the God of the Jews."

- ^ Footnote #4 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "See a collection and critical estimate of this evidence by Zimmern, Die Keilinschriften und das Alte Testament, 465 sqq."

- ^ Footnote #5 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Babel und Bibel, 1902. The enormous, and for the most part ephemeral, literature provoked by Delitzsch's lecture cannot be cited here.

- ^ Footnote #6 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Denkschriften d. Wien. Akad., L. iv. p. 115 seq. (1904)."

- ^ Footnote #7 from Page 313 of the 1911 E.B. reads: "Wo lag das Paradies? (1881), pp. 158-166."

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public ___domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

See also

Other articles relating to the Tetragrammaton:

Other:

- Names of God in Judaism

- El (god)

- Elohim

- Jah

- Yam (god)

- -ihah

- INRI

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Theophoric names

External links

- Preface to the Holy Name Bible

- A Discussion of the pronunciation of YHWH, including a new theory that explains all theophoric elements

- The Historical Evolution of the Hebrew God

- Tetragrammaton from Presbyterian perspective and with a Czech-Hebrew flavour.

- Biblaridion magazine: Phanerosis Theology: The Tetragrammaton and God's manifestation.

- Easton's Bible Dictionary (3rd ed.) 1887. "Jehovah."

- HaVaYaH the Tetragrammation in the Jewish Knowledge Base on Chabad.org

- The Divine Name in Norway

- Opinions about the Name

- Titles of Deity, a Christadelphian view

- Jewish Encyclopedia count of number of times the Tetragrammation is used

- Discovery and use of the Divine Name since the early 1960's in South Africa.

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume 8. 1910. "Jehovah (Yahweh)."

- Pronunciation (Audio) of Yahweh

- Encyclopedia Mythica. 2004. Arbel, Ilil. "Yahweh."

- Bibliography on the Tetragrammaton in the Dead Sea Scrolls

- YHWH/YHVH -- Tetragrammaton

- The Name

- The Meaning of the Tetragrammaton in Epistemology and Propositional Calculus

- Theological and Practical Aspects of the Tetragrammaton by Stanley C. Stein

- The Sacred Name Yahweh, a publication by Qadesh La Yahweh Press

- Allusions to YHWH in Christian scriptures, worship, and iconography