Utente:Panjabi/Prove

| Renna | |

|---|---|

| File:Nordamerikanisches Rentier.jpg | |

| Stato di conservazione | |

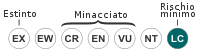

Rischio minimo[1] | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Ordine | Artiodactyla |

| Famiglia | Cervidae |

| Sottofamiglia | Capreolinae |

| Genere | Rangifer Smith |

| Specie | R. tarandus |

| Nomenclatura binomiale | |

| Rangifer tarandus (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

La renna (Rangifer tarandus), nota in Nordamerica come caribù, è un mammifero artiodattilo della famiglia dei Cervidi che abita le regioni artiche e subartiche con popolazioni sia stanziali che migratrici. Sebbene sia molto diffusa e numerosa[1], alcune sue sottospecie sono piuttosto rare e una di esse (o due, a seconda della tassonomia) è già estinta[2][3].

Le renne variano considerevolmente in colore e dimensioni[4] ed entrambi i sessi presentano palchi, sebbene questi ultimi siano più sviluppati nei maschi; in alcune popolazioni, tuttavia, le femmine sono completamente prive di palchi[5].

La caccia alle renne selvatiche e l'allevamento di renne semi-domestiche (per carne, pelle, palchi, latte e trasporto) sono attività molto importanti per alcuni popoli artici e subartici[6]. Perfino nelle zone lontane dal suo areale questo animale è ben conosciuto, grazie al ben consolidato mito, originatosi probabilmente in America agli inizi del XIX secolo, della slitta di Babbo Natale trainata da renne volanti, caratteristico elemento natalizio ormai da moltissimi anni[7]. Ancora oggi, in Lapponia, le renne vengono utilizzate per trainare le slitte[8].

Distribuzione e habitat

La renna è una specie numerosa e largamente diffusa nelle regioni olartiche settentrionali, essendo presente sia nella tundra che nella taiga (foresta boreale)[9]. Originariamente, la renna viveva in Scandinavia, Europa orientale, Russia, Mongolia e Cina settentrionale, a nord del 50° parallelo. In Nordamerica, era diffusa in Canada, Alaska (USA) e nelle regioni più settentrionali degli USA, dallo Stato di Washington al Maine. Nel XIX secolo era ancora presente nell'Idaho meridionale. Viveva anche a Sakhalin, in Groenlandia e, probabilmente anche in tempi storici, in Irlanda. Alla fine del Pleistocene, le renne si spingevano a sud fino al Nevada e al Tennessee in Nordamerica e alla Spagna in Europa[9][10]. Oggi, le renne selvatiche sono scomparse da molte aree del loro areale storico, specialmente nelle sue regioni meridionali, dove sono scomparse quasi ovunque. Numerose popolazioni di renne selvatiche, tuttavia, sono ancora presenti in Norvegia, nella regione di Markku in Finlandia, Svezia, Siberia, Groenlandia, Alaska e Canada.

Le renne domestiche sono diffuse soprattutto in Fennoscandia settentrionale e Russia; una mandria di circa 150-170 capi vive nella regione dei Cairngorms, in Scozia. Le ultime popolazioni selvatiche di renne della tundra si incontrano in alcune parti della Norvegia meridionale[11].

Alcune renne provenienti dalla Norvegia furono introdotte nella Georgia Australe, un'isola dell'Atlantico meridionale, agli inizi del XX secolo. Oggi sull'isola si trovano ancora due mandrie di questi animali, perennemente separate tra loro dai ghiacciai. Il loro numero totale non supera il migliaio di capi. L'immagine di questo animale compare anche sulla bandiera e sullo stemma del Territorio. Circa 4000 renne furono introdotte inoltre nell'arcipelago subantartico francese delle Isole Kerguelen. Una piccola mandria di circa 2500-3000 capi vive nelle regioni orientali dell'Islanda[12].

Il numero dei caribù e delle renne ha sempre subito fluttuazioni in passato, ma oggi molte popolazioni sono in grave diminuzione in tutto l'areale della specie[13]. Le popolazioni di renne e caribù più settentrionali, dalle abitudini migratorie, stanno diminuendo sempre più a causa degli effetti dovuti ai mutamenti climatici, mentre la sopravvivenza delle popolazioni stanziali di caribù è messa a repentaglio dall'inquinamento causato dalle industrie[14].

Descrizione

Dimensioni

Le femmine di solito misurano 162-205 cm di lunghezza e pesano 79-120 kg[4][15]. I maschi, generalmente, sono più grandi (sebbene le loro dimensioni varino a seconda delle sottospecie): misurano 180-214 cm di lunghezza e 92-210 kg di peso; in casi eccezionali alcuni esemplari notevolmente sviluppati hanno raggiunto i 318 kg[4][15]. L'altezza al garrese è di 85-150 cm e la coda è lunga 14-20 cm[4]. La sottospecie R. t. platyrhynchus, delle Isole Svalbard, è molto piccola se paragonata ad altre sottospecie (fenomeno, questo, noto come nanismo insulare): le femmine misurano circa 150 cm di lunghezza e pesano intorno ai 53 kg in primavera e ai 70 kg in autunno[16]. I maschi, invece, sono lunghi all'incirca 160 cm e pesano attorno ai 65 kg in primavera e ai 90 kg in autunno[16]. Le renne delle Svalbard hanno anche zampe relativamente più corte e un'altezza al garrese che non supera gli 80 cm[4][16], così come stabilito dalla regola di Allen. Le renne domestiche hanno zampe più corte e costituzione più pesante delle loro cugine selvatiche.

Mantello

Il colore del mantello varia considerevolmente, sia da un esemplare all'altro che a seconda delle stagioni e della sottospecie. Le popolazioni settentrionali, solitamente di dimensioni minori, hanno un mantello dai toni più bianchi, mentre quelle meridionali, di dimensioni maggiori, hanno mantelli più scuri. Questa caratteristica si può vedere bene in Nordamerica, dove la sottospecie più settentrionale, il caribù di Peary, è quella con il mantello più bianco, oltre che la più piccola sottospecie del continente, mentre la sottospecie più meridionale, il caribù dei boschi, è la più scura e la più grande[17]. Il manto è costituito da due strati di pelo, un folto sottopelo lanoso e uno strato di peli più lunghi, cavi e pieni d'aria.

Palchi

Nella maggior parte delle popolazioni entrambi i sessi sono muniti di palchi[5], i quali (nella varietà della Scandinavia) cadono a dicembre nei maschi più anziani, all'inizio della primavera in quelli più giovani e d'estate nelle femmine. Generalmente i palchi sono costituiti da due gruppi separati di punte, uno inferiore, l'altro superiore. Le dimensioni dei palchi variano a seconda della sottospecie (ad esempio quelle più settentrionali hanno palchi più piccoli e sottili)[17]; i palchi di alcune sottospecie sono superati per dimensioni solamente da quelli dell'alce e possono misurare fino a 100 cm di larghezza e 135 cm di lunghezza. Rispetto alle dimensioni del corpo, la renna è il Cervide con i palchi più grandi[5].

Naso e zoccoli

All'interno del naso della renna è presente un apparato di turbinati che accresce notevolmente la superficie interna delle narici. L'aria fredda proveniente dall'esterno viene riscaldata dal calore corporeo dell'animale prima di arrivare ai polmoni e l'acqua che si condensa con l'espirazione viene raccolta prima che l'animale termini il respiro: quest'acqua inumidisce l'aria inspirata e molto probabilmente viene anche assorbita nel sangue attraverso le mucose nasali.

Gli zoccoli della renna si adattano ad ogni stagione: in estate, quando il terreno della tundra è soffice e umido, i cuscinetti plantari si comportano come una spugna e consentono una migliore aderenza. In inverno, invece, essi si restringono sempre più e rimane allo scoperto solamente l'estremità dello zoccolo, che penetra facilmente nel ghiaccio e nella neve impedendo all'animale di scivolare. This also enables them to dig down (an activity known as "cratering")[18][19] through the snow to their favorite food, a lichen known as reindeer moss. The knees of many species of reindeer are adapted to produce a clicking sound as they walk.[20]

Ecology and behavior

Diet

Template:Fix bunching Reindeer are ruminants, having a four-chambered stomach. They mainly eat lichens in winter, especially reindeer moss. However, they also eat the leaves of willows and birches, as well as sedges and grasses. There is some evidence to suggest that on occasion, they will also feed on lemmings,[21] arctic char, and bird eggs.[22] Reindeer herded by the Chukchis have been known to devour mushrooms enthusiastically in late summer.[23]

Reproduction

Mating occurs from late September to early November. Males battle for access to females. Two males will lock each other's antlers together and try to push each other away. The most dominant males can collect as many as 15-20 females to mate with. A male will stop eating during this time and lose much of its body reserves.

Calves may be born the following May or June. After 45 days, the calves are able to graze and forage but continue suckling until the following autumn and become independent from their mothers.

Migration

Some populations of the North American caribou migrate the furthest of any terrestrial mammal, traveling up to 5 000 km (3 100 mi) a year, and covering 1 000 000 km² (390 000 mi²).[1][24] Other populations (e.g., in Europe) have a shorter migration, and some, for example the subspecies R. t. pearsoni and R. t. platyrhynchus (both restricted to islands), are residents that only make local movements.

Normally travelling about 19–55 km (12–34 mi) a day while migrating, the caribou can run at speeds of 60–80 km/h (37–50 mph).[1] During the spring migration smaller herds will group together to form larger herds of 50,000 to 500,000 animals but during autumn migrations, the groups become smaller, and the reindeer begin to mate. During the winter, reindeer travel to forested areas to forage under the snow. By spring, groups leave their winter grounds to go to the calving grounds. A reindeer can swim easily and quickly, normally at 6,5 km/h (4,0 mph) but if necessary at 10 km/h (6,2 mph), and migrating herds will not hesitate to swim across a large lake or broad river.[1]

Predators

There are a variety of predators that prey heavily on reindeer. Golden Eagles prey on calves and are the most prolific hunter on calving grounds.[25] Wolverine will take newborn calves or birthing cows, as well as (less commonly) infirm adults. Brown Bears and (in the rare cases where they encounter each other) Polar bears prey on reindeer of all ages but (as with the wolverine) are most likely to attack weaker animals such as calves and sick deer. The Gray Wolf is the most effective natural predator of adult reindeer, especially during the winter. As carrion, caribou are fed on by foxes, ravens and hawks. Blood-sucking insects, such as black flies and mosquitoes, are a plague to reindeer during the summer and can cause enough stress to inhibit feeding and calving behaviors.[26] In one case, the entire body of a reindeer was found in a Greenland shark (possibly a case of scavenging),[27] a species found in the far northern Atlantic. The population numbers of some of these predators is influenced by the migration of reindeer. During the Ice Ages, they faced Dire wolves, Cave lions, American lions, Short-faced bears, Cave hyenas, Smilodons, Jaguars, Cougars, and possibly the ground sloth.[senza fonte]

Subspecies

Since 1961, reindeer have been divided into two major groups, the tundra reindeer with six subspecies and the woodland reindeer with three subspecies.[senza fonte] Among the tundra subspecies are small-bodied, high-Arctic island forms. These island subspecies are probably not closely related, since the Svalbard Reindeer seems to have evolved from large European Reindeer, whereas Peary Caribou and the extinct Arctic Reindeer are closely related and probably evolved in high-Arctic North America.[2]

The following list is partial, as four subspecies which are restricted to Russia and neighbouring regions have been left out. These are R. tarandus buskensis, R. tarandus pearsoni (Novaya Zemlya Reindeer), R. tarandus phylarchus (Kamchatka/Okhotsk Reindeer) and R. tarandus sibiricus (Siberian Tundra Reindeer).[28]

Tundra reindeer

- †Arctic Reindeer (R. tarandus eogroenlandicus), an extinct subspecies found until 1900 in eastern Greenland.

- Peary Caribou (R. tarandus pearyi), found in the northern islands of the Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada.

- Svalbard Reindeer (R. tarandus platyrhynchus), found on the Svalbard islands of Norway, is the smallest subspecies of reindeer.

- Markku Caribou (R. tarandus vixaroonicus), found in the Markku region of Finland.

- Mountain/Wild Reindeer (R. tarandus tarandus), found in the Arctic tundra of Eurasia, including the Fennoscandia peninsula of northern Europe.

- Porcupine Caribou or Grant's Caribou (R. tarandus granti), which are found in Alaska, the Yukon, and the Northwest Territories of Canada. Very similar to R. tarandus groenlandicus, and probably better regarded as a junior synonym of that subspecies.[28][29]

- Barren-ground Caribou (R. tarandus groenlandicus), found in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories of Canada and in western Greenland.

Woodland reindeer

- Finnish Forest Reindeer (R. tarandus fennicus), found in the wild in only two areas of the Fennoscandia peninsula of Northern Europe, in Finnish/Russian Karelia, and a small population in central south Finland. The Karelia population reaches far into Russia, however, so far that it remains an open question whether reindeer further to the east are R. t. fennicus as well.

- Migratory Woodland Caribou (R. tarandus caribou), or Forest Caribou, once found in the North American taiga (boreal forest) from Alaska to Newfoundland and Labrador and as far south as New England, Idaho, and Washington. Woodland Caribou have disappeared from most of their original southern range and are considered threatened where they remain, with the notable exception of the Migratory Woodland Caribou of northern Quebec and Labrador, Canada. The name of the Cariboo district of central British Columbia relates to their once-large numbers there, but they have almost vanished from that area in the last century. A herd is protected in the Caribou Mountains in Alberta. The above quoted range includes R. tarandus caboti (Labrador Caribou), R. tarandus osborni (Osborn's Caribou – from British Columbia) and R. tarandus terraenovae (Newfoundland Caribou). Based on a review in 1961, these were considered invalid and included in R. tarandus caribou, but some recent authorities have considered them all valid, even suggesting that they are quite distinct.[28][30] An analysis of mtDNA in 2005 found differences between the caribous from Newfoundland, Labrador, south-western Canada and south-eastern Canada, but maintained all in R. tarandus caribou.[29]

- †Queen Charlotte Islands Caribou (R. tarandus dawsoni) from the Queen Charlotte Islands was believed to represent a distinct subspecies. It became extinct at the beginning of the 20th century. However, recent DNA analysis from mitochondrial DNA of the remains from those reindeer suggest that the animals from the Queen Charlotte Islands were not genetically distinct from the Canadian mainland reindeer subspecies.[3]

Reindeer and humans

Hunting

Reindeer hunting by humans has a very long history, and caribou/wild reindeer "may well be the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting."[6]

Humans started hunting reindeer in the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, and humans are today the main predator in many areas. Norway and Greenland have unbroken traditions of hunting wild reindeer from the ice age until the present day. In the non-forested mountains of central Norway, such as Jotunheimen, it is still possible to find remains of stone-built trapping pits, guiding fences, and bow rests, built especially for hunting reindeer. These can, with some certainty, be dated to the Migration Period, although it is not unlikely that they have been in use since the Stone Age.

Norway is now preparing to apply for nomination as a World Heritage Site for areas with traces and traditions of reindeer hunting in Dovrefjell-Sunndalsfjella National Park, Reinheimen National Park and Rondane National Park in Central Sør-Norge (Southern Norway). There is in these parts of Norway an unbroken tradition of reindeer hunting from post-glacial stone age until today.

Wild caribou are still hunted in North America and Greenland. In the traditional lifestyle of the Inuit people, Northern First Nations people, Alaska Natives, and the Kalaallit of Greenland, the caribou is an important source of food, clothing, shelter, and tools. Many Gwichʼin people, who depend on the Porcupine caribou, still follow traditional caribou management practices that include a prohibition against selling caribou meat and limits on the number of caribou to be taken per hunting trip.[31]

The blood of the caribou was supposedly mixed with alcohol as drink by hunters and loggers in colonial Quebec to counter the cold. This drink is now enjoyed without the blood as a wine and whiskey drink known as Caribou.[32][33]

Reindeer husbandry

Reindeer have been herded for centuries by several Arctic and Subarctic people including the Sami and the Nenets. They are raised for their meat, hides, antlers and, to a lesser extent, for milk and transportation. Reindeer are not considered fully domesticated, as they generally roam free on pasture grounds. In traditional nomadic herding, reindeer herders migrate with their herds between coast and inland areas according to an annual migration route, and herds are keenly tended. However, reindeer were not bred in captivity, though they were tamed for milking as well as for use as draught animals or beasts of burden.

The use of reindeer as semi-domesticated livestock in Alaska was introduced in the late 19th century by the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, with assistance from Sheldon Jackson, as a means of providing a livelihood for Native peoples there.[34] Reindeer were imported first from Siberia, and later also from Norway. A regular mail run in Wales, Alaska, used a sleigh drawn by reindeer.[35] In Alaska, reindeer herders use satellite telemetry to track their herds, using online maps and databases to chart the herd's progress.

Economy

The reindeer has (or has had) an important economic role for all circumpolar peoples, including the Saami, Nenets, Khants, Evenks, Yukaghirs, Chukchi, and Koryaks in Eurasia. It is believed that domestication started between the Bronze and Iron Ages. Siberian deer owners also use the reindeer to ride on (Siberian reindeer are larger than their Scandinavian relatives). For breeders, a single owner may own hundreds or even thousands of animals. The numbers of Russian herders have been drastically reduced since the fall of the Soviet Union. The fur and meat is sold, which is an important source of income. Reindeer were introduced into Alaska near the end of the 19th century; they interbreed with native caribou subspecies there. Reindeer herders on the Seward Peninsula have experienced significant losses to their herds from animals (such as wolves) following the wild caribou during their migrations.

Reindeer meat is popular in the Scandinavian countries. Reindeer meatballs are sold canned. Sautéed reindeer is the best-known dish in Lapland. In Alaska and Finland, reindeer sausage is sold in supermarkets and grocery stores. Reindeer meat is very tender and lean. It can be prepared fresh, but also dried, salted, hot- and cold-smoked. In addition to meat, almost all internal organs of reindeer can be eaten, some being traditional dishes.[36] Furthermore, Lapin Poron liha fresh Reindeer meat completely produced and packed in Finnish Lapland is protected in Europe with PDO classification.[37][38]

Reindeer antler is powdered and sold as an aphrodisiac, nutritional or medicinal supplement to Asian markets.

Caribou have been a major source of subsistence for Canadian Inuit.

In history

Both Aristotle and Theophrastus have short accounts - probably based on the same source - of an ox-sized deer species, named tarandos, living in the land of the Bodines in Scythia, which was able to change the colour of its fur to obtain camouflage. The latter is probably a misunderstanding of the seasonal change in reindeer fur colour. The descriptions have been interpreted as being of reindeer living in the southern Ural Mountains at c. 350 BC[39]

A deer-like animal described by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (chapter 6.26) from the Hercynian Forest in the year 53 BC is most certainly to be interpreted as reindeer:[39][40]

According to Olaus Magnus's Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus - printed in Rome in 1555 - Gustav I of Sweden sent 10 reindeer to Albert I, Duke of Prussia, in the year 1533. It may be these animals that Conrad Gessner had seen or heard of.

Name etymology

The name rangifer, which Linnaeus chose as the name for the reindeer genus, was used by Albertus Magnus in his De animalibus, fol. Liber 22, Cap. 268: "Dicitur Rangyfer quasi ramifer". This word may go back to a Saami word raingo.[39] For the origin of the word tarandus, which Linnaeus chose as the species epithet, he made reference to Ulisse Aldrovandi's Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia fol. 859—863, Cap. 30: De Tarando (1621). However, Aldrovandi - and before him Konrad Gesner[41] - thought that rangifer and tarandus were two separate animals.[42] In any case, the tarandos name goes back to Aristotle and Theophrastus - see above.

Local names

The name rein (-deer) is of Norse origin (Old Norse hreinn, which again goes back to Proto-Germanic *hraina and Proto-Indo-European *kroino meaning "horned animal"). In the Finno-Permic languages, Sami poatsu (in Northern Sami boazu, in Lule Sami boatsoj, in Pite Sami båtsoj, in Southern Sami bovtse), Mari pučə and Udmurt pudžej, all referring to domesticated reindeer, go back to *počaw, an Iranian loanword deriving from Proto-Indo-European *peḱu-, meaning "cattle". The Finnish name poro may also stem from the same.[43] The name caribou comes, through French, from Mi'kmaq qalipu, meaning "snow shoveler", referring to its habit of pawing through the snow for food.[44] In Inuktitut, the caribou is known by the name tuttuk (Labrador dialect). In Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi dialects the caribou is called atihkw.

Reindeer in Christmas

Santa Claus's reindeer

In the Santa Claus myth, Santa Claus's sleigh is pulled by flying reindeer. These were first named in the 1823 poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas", where they are called Dasher, Dancer, Prancer, Vixen, Comet, Cupid, Dunder, and Blixem.[45] Dunder was later changed to Donder and—in other works—Donner (in German, "thunder"), and Blixem was later changed to Bliksem, then Blitzen (German for "lightning"). Some consider Rudolph as part of the group as well, though he was not part of the original named work referenced previously. Rudolph was added by Robert L. May in 1939 as "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer".

According to the British comedy panel game QI, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and all of Santa's other reindeer must be either female or castrated, because male reindeer lose their antlers during winter.

Heraldry and symbols

Several Norwegian municipalities have one or more reindeer depicted in their coats-of-arms: Eidfjord, Porsanger, Rendalen, Tromsø, Vadsø, and Vågå. The historic province of Västerbotten in Sweden has a reindeer in its coat of arms. The present Västerbotten County has very different borders and uses the reindeer combined with other symbols in its coat-of-arms. The city of Piteå also has a reindeer. The logo for Umeå University features three reindeer.

The Canadian quarter features a depiction of a caribou on one face. The caribou is the official provincial animal of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada, and appears on the coat of arms of Nunavut. A caribou statue was erected at the center of the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial, marking the spot in France where hundreds of soldiers from Newfoundland were killed and wounded in the First World War.

Two municipalities in Finland have reindeer motifs in their coats-of-arms: Kuusamo[46] has a running reindeer and Inari[47] a fish with reindeer antlers.

| Arini | |

|---|---|

| Ara ararauna | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Aves |

| Ordine | Psittaciformes |

| Famiglia | Psittacidae |

| Sottofamiglia | Arinae |

| Generi | |

| circa 32, vedi lista | |

Gli Arini (Arinae) sono una delle cinque sottofamiglie in cui si suddivide la famiglia degli Psittacidi. Alcune specie ed uno dei 32 generi attuali si sono estinti negli ultimi secoli. Nonostante siano noti solamente pochi resti fossili di pappagalli moderni, la maggior parte di essi appartiene a specie della famiglia degli Arini. Dal loro ritrovamento gli studiosi hanno attestato che a partire dal Pleistocene, pochi milioni di anni fa, molti generi di Arini erano già presenti.

Gli Arini si suddividono in due gruppi principali, chiamati comunemente clade a coda corta e clade a coda lunga. Alcuni studiosi ritengono che tali gruppi vadano elevati al rango di tribù o perfino di sottofamiglie[48].

Elenco dei generi

- Alipiopsitta (1 specie)

- Amazona (30 specie viventi più 2 scomparse recentemente)

- Anodorhynchus (3 specie)

- Ara (8 specie viventi più 5 scomparse recentemente)

- Aratinga (20 specie viventi più 1 scomparsa recentemente)

- Bolborhynchus (3 specie)

- Brotogeris (8 specie)

- Conuropsis (1 specie scomparsa recentemente)

- Cyanoliseus (1 specie)

- Cyanopsitta (1 specie)

- Deroptyus (1 specie)

- Diopsittaca (1 specie)

- Enicognathus (2 specie)

- Forpus (7 specie)

- Graydidascalus (1 specie)

- Guaruba (1 specie)

- Hapalopsittaca (4 specie)

- Leptosittaca (1 specie)

- Myiopsitta (1 specie)

- Nandayus (1 specie)

- Nannopsittaca (2 specie)

- Ognorhynchus (1 specie)

- Orthopsittaca (1 specie)

- Pionites (2 specie)

- Pionopsitta (1 specie)

- Pionus (7 specie)

- Primolius (3 specie)

- Psilopsiagon (2 specie)

- Pyrilia (7 specie)

- Pyrrhura (20 specie)

- Rhynchopsitta (2 specie)

- Touit (8 specie)

- Triclaria (1 specie)

| Psittaciformi [49] | |

|---|---|

| Agapornis roseicollis | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Aves |

| Ordine | Psittaciformes |

| Famiglie | |

Gli Psittaciformi [50] (Psittaciformes [51][52] Wagler, 1830) sono un ordine di uccelli che comprende circa 372 specie di pappagalli suddivise in 86 generi; vivono soprattutto nelle regioni calde e tropicali. L'ordine viene suddiviso in tre famiglie: gli Psittacidi (pappagalli «veri»), i Cacatuidi (cacatua) e gli Strigopidi (pappagalli della Nuova Zelanda) [53] . Generalmente i pappagalli hanno una distribuzione pantropicale, ma alcune specie si incontrano anche nelle regioni temperate dell'Emisfero Australe. La maggiore diversità di specie si incontra in Sudamerica ed Australasia.

Tra i più importanti aspetti che caratterizzano i pappagalli vi sono il robusto becco ricurvo, la posizione eretta che mantengono quando sono appollaiati, le zampe robuste e i piedi zigodattili muniti di forti unghie. La maggior parte delle specie hanno un colore prevalentemente verde, spesso unito ad altri colori brillanti, ma altre sono variopinte. I cacatua variano in colorazione dal bianco al nero ed esibiscono una cresta mobile di penne sulla sommità della testa. In quasi tutti i pappagalli il dimorfismo sessuale è scarso o assente. Per quanto riguarda la lunghezza hanno le dimensioni più variabili tra tutti gli uccelli.

L'alimentazione dei pappagalli è composta soprattutto da semi, noci, frutta, gemme e altre sostanze vegetali. Poche specie mangiano anche ratti e vermi e i Lorini sono specializzati nel mangiare nettare dei fiori e frutti morbidi. Quasi tutti i pappagalli nidificano nelle cavità degli alberi (o, in cattività, nelle scatole-nido) e depongono uova bianche da cui sgusciano piccoli inetti.

I pappagalli, insieme a corvi, cornacchie, ghiandaie e gazze, sono tra gli uccelli più intelligenti e l'abilità di alcune specie nell'imitare la voce umana li ha resi molto popolari come animali domestici. La cattura di esemplari selvatici per il mercato degli animali da compagnia, la caccia, la deforestazione e la compezione con le specie invasive ha notevolmente diminuito il numero dei pappagalli selvatici e questi animali stanno tuttora subendo uno sfruttamento da parte dell'uomo maggiore di quello di ogni altro gruppo di uccelli [54] . Le recenti misure di conservazione volte a proteggere l'habitat di alcune tra le più importanti specie di pappagallo sono servite anche a proteggere molte specie meno note che vivono nello stesso ecosistema [55] .

Evoluzione e sistematica

Origini ed evoluzione

Le ricerche che cercano di svelare l'origine dei pappagalli sono tuttora in corso. La maggiore diversità di specie che si incontra in Sudamerica ed Australasia sembra indicare che l'ordine degli Psittaciformi abbia avuto origine nel Gondwana, con centro di diffusione in Australasia [56] . La scarsità dei resti fossili di uccello, tuttavia, rende molto difficile valutare la certezza di questa ipotesi.

Si ritiene che il più antico fossile di pappagallo, risalente al Cretaceo superiore (circa 70 milioni di anni fa), sia un singolo frammento, lungo 1002 mm, del ramo inferiore di un grosso becco ritrovato nei depositi della Formazione di Lance Creek nella Contea di Niobrara (Wyoming) [57] . Vari studiosi, tuttavia, ritengono con certezza che questo fossile non appartenga a un uccello, ma ad un teropode cenagnatide o ad un altro dinosauro non-aviario munito di un becco simile a quello di un uccello [58][59] .

Al giorno d'oggi si ritiene generalmente che gli Psittaciformi o gli antenati che hanno in comune con altri uccelli fossero già presenti al periodo della scomparsa dei dinosauri, circa 65 milioni di anni fa. Se fosse così, i pappagalli probabilmente non sono creature che svilupparono autapomorfie morfologiche, ma i discendenti di uccelli arboricoli generalisti abbastanza simili (ma non necessariamente imparentati) ai nittibi e ai bocca di rana odierni.

Il luogo di origine dei primi pappagalli fossili è l'Europa. Il reperto più antico è un osso alare di Mopsitta tanta scoperto in Danimarca e risalente a 54 milioni di anni fa [60] . All'epoca la regione aveva un clima tropicale dovuto al cosiddetto «Massimo Termico Paleocene-Eocene».

Fossili di età successiva risalgono all'Eocene, periodo iniziato circa 50 milioni di anni fa. Alcuni fossili quasi completi di uccelli simili a pappagalli sono stati rinvenuti in Inghilterra e Germania [61] . Sembra più probabile, però, che questi fossili non appartengano ai diretti antenati dei pappagalli moderni, ma piuttosto a linee evolutive loro imparentate che si evolvettero nell'Emisfero Boreale e scomparvero senza lasciare discendenti. Probabilmente non sono quindi «anelli mancanti» tra pappagalli ancestrali e moderni, ma piuttosto linee di Psittaciformi che si evolvettero parallelamente ai pappagalli veri e ai cacatua, sviluppando le loro peculiari autapomorfie:

- Psittacopes (Eocene inferiore/medio di Geiseltal, Germania) – forma basale?

- Serudaptus – pseudasturide o psittacide?

- Pseudasturidae (o più correttamente Halcyornithidae)

- Pseudasturides- in passato Pseudastur

- Vastanavidae

- Vastanavis (Eocene inferiore di Vastan, India)

- Quercypsittidae

- Quercypsitta (Eocene superiore)

I più antichi resti fossili di pappagalli moderni risalgono a circa 23-20 milioni di anni fa e provengono anch'essi dall'Europa. I resti fossili successivi - di nuovo di provenienza europea - consistono di ossa chiaramente attribuibili a pappagalli di tipo moderno. Per quanto riguarda questo periodo l'Emisfero Australe non è così ricco di fossili come quello boreale e i primi fossili attribuibili a pappagalli risalgono solo al Miocene inferiore o medio, circa 20 milioni di anni fa. A questo periodo, tuttavia, risale già una mascella superiore fossile indistinguibile da quella dei moderni cacatua. In passato si ritenevano risalenti al Miocene anche altri resti fossili che successivamente sono stati datati più correttamente a 5 milioni di anni fa.

Tra i pappagalli fossili chiaramente attribuili agli Psittacidi o ai loro diretti antenati ricordiamo:

- Archaeopsittacus (Oligocene superiore/Miocene inferiore)

- Xenopsitta (Miocene inferiore della Repubblica Ceca)

- Psittacidae gen. e spp. indet. (Miocene inferiore/medio di Otago, Nuova Zelanda) - varie specie

- Bavaripsitta (Miocene medio di Steinberg, Germania)

- Psittacidae gen. e sp. indet. (Miocene medio della Francia) - erroneamente attribuito a Pararallus dispar, comprende Psittacus lartetianus

I seguenti fossili del Paleogene, invece, sembra non appartengano agli Psittaciformi:

- Palaeopsittacus (Miocene inferiore/medio dell'Europa nord-occidentale) - un caprimulgiforme (podargide?) o un quercypsittide?

- Precursor (Eocene inferiore) – una vera chimera, forse uno pseudasturide o uno psittacide

- Pulchrapollia (Eocene inferiore) – comprende il cosiddetto Primobucco olsoni - uno psittaciforme (pseudasturide o psittacide)?

Filogenesi

La filogenesi dei pappagalli è ancora sotto esame. La classificazione qua presente è quella ritenuta attualmente più valida, ma studi successivi potrebbero apportarvi delle modifiche. Proprio per questo motivo non va considerata una stesura definitiva.

Gli Psittaciformi comprendono tre linee evolutive principali: gli Strigopidi, gli Psittacidi (pappagalli veri) e i Cacatuidi (cacatua). In passato gli Strigopidi erano ritenuti un gruppo di Psittacidi, ma studi più recenti sembrano indicare che queste specie originarie della Nuova Zelanda vadano poste alla base dell'albero filogenetico dei pappagalli, ben distanti sia dagli Psittacidi che dai Cacatuidi [56][62][63] .

Anche i Cacatuidi sono piuttosto diversi dagli Psittacidi: presentano una cresta mobile sulla testa, una diversa disposizione delle arterie carotidi, una cistifellea e alcune differenze nelle ossa del cranio; sono inoltre privi delle cosiddette penne «a testura Dick» che, negli Psittacidi, diffondono la luce in maniera tale da produrre i tipici colori vibranti tipici di molti pappagalli. Le penne colorate con alti livelli di psittacofulvina resistono meglio di quelle bianche agli attacchi del batterio Bacillus licheniformis [64] .

In passato i lorichetti venivano classificati in una terza famiglia, i Loriidi [65] , ma gli studi sul DNA hanno dimostrato che sono Psittacidi a tutti gli effetti, strettamente imparentati con i pappagalli dei fichi (due dei tre generi che costituiscono la tribù dei Cyclopsittacini della sottofamiglia degli Psittacini) e il pappagallino ondulato (tribù dei Melopsittacini della sottofamiglia dei Platicercini) [56][62][63] .

Sistematica

La seguente classificazione indica le varie sottofamiglie degli Psittaciformi. I dati molecolari sembrano indicare che alcune di esse costituiscano famiglie vere e proprie, ma una corretta sistematica è ancora da definire.

Famiglia Strigopidae: pappagalli della Nuova Zelanda

- Tribù Nestorini: 1 genere con solo 2 specie viventi, il kea e il kaka della Nuova Zelanda;

- Tribù Strigopini: il kakapo della Nuova Zelanda, incapace di volare e gravemente minacciato.

Famiglia Cacatuidae: cacatua

- Sottofamiglia Microglossinae;

- Sottofamiglia Calyptorhynchinae: cacatua neri;

- Sottofamiglia Cacatuinae: cacatua bianchi.

Famiglia Psittacidae: pappagalli veri

- Sottofamiglia Arinae: pappagalli neotropicali, circa 160 specie suddivise in circa 30 generi. Probabilmente 2 linee evolutive distinte [62][66] ;

- Sottofamiglia Loriinae: circa una dozzina di generi con circa 50 specie di lorichetti e lori, originari soprattutto della Nuova Guinea, ma diffusi anche in Australia, Indonesia e nelle isole del Pacifico meridionale;

- Sottofamiglia Micropsittinae: 6 specie di pappagalli pigmei, appartenenti tutte ad un unico genere;

- Sottofamiglia Psittacinae

- Tribù Cyclopsittacini: pappagalli dei fichi, 3 generi, tutti originari della Nuova Guinea o delle isole vicine;

- Tribù Polytelini: tre generi originari dell'Australia e della Wallacea che in passato venivano classificati tra i pappagalli dalla coda larga;

- Tribù Psittrichadini: un'unica specie, il pappagallo di Pesquet;

- Tribù Psittacini: pappagalli afrotropicali, circa una dozzina di specie suddivise in 3 generi;

- Tribù Psittaculini: pappagalli psittaculini paleotropicali, circa 70 specie viventi suddivise in 12 generi diffuse dall'India all'Australasia.

- Subfamiglia Platycercinae: pappagalli dalla coda larga; circa 30 specie in una dozzina di generi

- Tribù Melopsittacini: un genere con una sola specie, il pappagallino ondulato;

- Tribù Neophemini: due piccoli generi di pappagalli;

- Tribù Pezoporini: un genere di pappagalli con due specie piuttosto diverse tra loro;

- Tribù Platycercini: roselle e loro simili; circa 20 specie suddivise in 8 generi.

Other lists

- A list of all parrots sortable by common or binomial name, about 350 species.

- Taxonomic list of Cacatuidae species, 21 species in 7 genera

- Taxonomic list of true parrots which provides the sequence of Psittacidae genera and species following a traditional two-subfamily approach, as in the taxobox above, about 330 species.

- List of Strigopidae

- List of macaws

- List of Amazon parrots

- List of Aratinga parakeets

Distribuzione

I pappagalli vivono nelle zone tropicali e subtropicali di tutti i continenti, essendo diffusi in Australia e isole del Pacifico, Asia meridionale, Sud-est asiatico, regioni meridionali del Nordamerica, Sudamerica e Africa. Alcune isole dei Caraibi e del Pacifico ospitano specie endemiche. Di gran lunga la maggiore diversità di specie si incontra in Australasia e Sudamerica. I lori e i lorichetti sono diffusi in un'area che da Sulawesi e Filippine si spinge fino all'Australia e alla Polinesia francese; il maggior numero di specie si incontra in Nuova Guinea e nelle aree circostanti. La sottofamiglia degli Arini, comprendente tutti i pappagalli neotropicali, tra cui amazzoni, ara e conuri, è distribuita dal Messico settentrionale e dalle Bahamas fino alla Terra del Fuoco, all'estremità meridionale del Sudamerica. I pappagalli pigmei, che costituiscono la sottofamiglia dei Micropsittini, appartengono tutti a un unico genere limitato alla Nuova Guinea. La sottofamiglia dei Nestorini è costituita da tre specie aberranti tutte originarie della Nuova Zelanda. I pappagalli dalla coda larga della sottofamiglia dei Platycercini sono ristretti ad Australia, Nuova Zelanda e isole del Pacifico (fino alle Figi). L'ultima sottofamiglia di pappagalli veri, gli Psittacini, occupa un vastissimo areale che da Australia e Nuova Guinea si spinge fino all'Asia meridionale e all'Africa. Il maggior numero di specie di cacatua vive in Australia e Nuova Guinea, ma alcune vivono anche nelle Isole Salomone, in Indonesia e alle Filippine (una specie estinta in passato viveva anche in Nuova Caledonia [67] ).

Alcune specie di pappagallo si spingono nelle fredde regioni temperate del Sudamerica e della Nuova Zelanda. Una specie, il parrocchetto della Carolina, viveva nelle regioni temperate del Nordamerica, ma venne cacciata fino alla sua totale scomparsa agli inizi del XX secolo. Numerose specie sono state introdotte in aree dal clima temperato e al giorno d'oggi si incontrano popolazioni stabili in alcuni Stati degli Stati Uniti, in Regno Unito e Spagna [68][69] .

Sebbene alcune specie di pappagallo siano sedentarie o perfino migratrici, la maggior parte di esse effettua brevi spostamenti stagionali e alcune hanno perfino adottato uno stile di vita nomade [70] .

Morfologia

Le specie attuali variano in dimensione dal pappagallo pigmeo facciacamoscio di meno di 10 g di peso e 8 cm di lunghezza all'ara giacinto di 1 m di lunghezza e al kakapo di 4 kg di peso. Tra le varie famiglie, quella degli Strigopidi comprende tre specie di notevoli dimensioni, così come quella dei cacatua. I pappagalli psittacidi, invece, variano moltissimo in dimensioni a seconda delle specie.

La principale caratteristica fisica che caratterizza maggiormente i pappagalli è il robusto becco largo e ricurvo. Il ramo superiore, dall'estremità appuntita, è prominente e ricurvo all'ingiù. Non è fuso alle ossa del cranio e così è in grado di muoversi indipendentemente, permettendo a questi uccelli di mordere esercitando una notevole pressione. Il ramo inferiore è più corto ed ha un margine tagliente molto affilato che poggia contro la porzione piatta del ramo superiore in modo simile ad un incudine. I pappagalli che si nutrono di semi hanno una lingua robusta che permette loro di manipolare i semi o le noci nel becco in posizione tale che le mandibole possano applicare meglio la loro pressione. La testa è grande e gli occhi sono posizionati lateralmente; la visione binoculare, quindi, è molto limitata, ma quella periferica aumenta notevolmente.

Le specie di cacatua hanno una cresta di penne mobili sulla sommità della testa che può essere sollevata e abbassata a piacere. Tale cresta non è presente in nessun'altra specie di pappagallo, ma i lorichetti del Pacifico dei generi Vini e Phigys sono in grado di arruffare le penne della corona e della nuca. Il colore predominante del piumaggio dei pappagalli è il verde, ma la maggior parte delle specie presenta anche piccole quantità di penne rosse o di altro colore. I cacatua costituiscono l'unica eccezione, poiché durante la loro storia evolutiva hanno perso completamente il colore verde e azzurro del piumaggio e ora sono generalmente bianchi o neri con alcune zone rosse, rosa o gialle. Tra i pappagalli non è presente un notevole dimorfismo sessuale, ma vi sono comunque alcune eccezioni, prima tra tutte il pappagallo eclettico.

Comportamento

Studiare i pappagalli in natura presenta notevoli difficoltà, poiché sono difficili da catturare e una volta presi è molto difficile anche riuscirli a marcare. Gran parte delle ricerche svolte su uccelli selvatici si basano sull'applicazione di anelli (o bande) alle zampe o di targhette alle ali, ma i pappagalli tendono a toglierseli poco dopo [70] ; inoltre, si spostano su areali molto vasti. Di conseguenza sono tuttora presenti moltre lacune per quanto riguarda la conoscenza del loro comportamento.

I pappagalli hanno un volo sostenuto e diretto. La maggior parte delle specie trascorre gran parte del tempo appollaiata sui rami della volta della foresta. Spesso utilizzano il becco per arrampicarsi o appendersi a rami o ad altri supporti. Al suolo camminano solitamente con passo ondeggiante.

Dieta

La dieta dei pappagalli è costituita da semi, frutta, nettare, polline, gemme e, talvolta, insetti, ad esempio blatte, e altri piccoli animali. Senza dubbio, però, i componenti fondamentali della dieta dei pappagalli veri e dei cacatua sono i semi. L'evoluzione di becchi grandi e potenti può essere interpratata principalmente come un adattamento per aprire e mangiare i semi. Tutti i pappagalli veri, a eccezione del pappagallo di Pesquet, utilizzano lo stesso metodo per liberare i semi dal guscio: tengono il seme tra le mandibole e con quella inferiore frantumano il guscio; quindi il seme viene fatto ruotare nel becco e il guscio rimanente viene rimosso [70] . Per tenere fermi i semi più grossi i pappagalli talvolta utilizzano anche un piede. I pappagalli sono soprattutto razziatori di semi e non loro dispersori; in molti casi alcune specie sono state viste mangiare dei frutti solamente per poter arrivare al seme. Dato che spesso i semi sviluppano un qualche veleno per proteggersi, i pappagalli sono in grado di rimuovere l'involucro e altre parti tossiche del frutto prima di ingerirlo. Molte specie delle Americhe, dell'Africa e della Nuova Guinea consumano argilla, utile sia per rilasciare sali minerali che per assorbire sostanze tossiche all'interno del tubo digerente [71] .

I lori e i lorichetti, il pappagallo di Latham e il pappagallo acrobata delle Filippine si nutrono soprattutto di nettare e polline e sono dotati di lingue dall'estremità a spazzola con cui raccolgono queste particolari fonti di cibo; inoltre il loro apparato digerente ha sviluppato particolari adattamenti per assorbire queste sostanze [72] . Il nettare, tuttavia, quando è disponibile, viene consumato anche da molte altre specie.

Oltre che di semi e fiori, alcuni pappagalli si nutrono anche di animali. Il parrocchetto alidorate cattura chiocciole acquatiche e il famoso kea della Nuova Zelanda è in grado di uccidere giovani petrelli e perfino di attaccare e uccidere indirettamente pecore adulte [73] . Un altro pappagallo neozelandese, il parrocchetto delle Antipodi, si introduce nelle tane degli uccelli delle tempeste dorsogrigio per uccidere gli adulti che covano le uova [74] . Alcuni cacatua e il kaka scavano cavità nei rami e nel legno per trovare larve.

Breeding

Although there are a few exceptions, parrots are monogamous breeders which nest in cavities and hold no territories other than their nesting sites.[70][75] The pair bonds of the parrots and cockatoos are strong and the pair will remain close even during the non-breeding season, even if they join larger flocks. As with many birds pair bond formation is preceded by courtship displays; these are relatively simple in the case of cockatoos. In Psittacidae parrots common breeding displays, usually undertaken by the male, include slow deliberate steps known as a "parade" or "stately walk" and the "eye-blaze", where the pupil of the eye constricts to reveal the edge of the iris.[70] Allopreening is used by the pair to help maintain the bond. Cooperative breeding, where birds other than the breeding pair help the pair raise the young and is common in some bird families, is extremely rare in parrots, and has only unambiguously been demonstrated in the Golden Parakeet (which may also exhibit polyamorous or group breeding system with multiple females contributing to the clutch).[76]

Only the Monk Parakeet and five species of Agapornis lovebird build nests in trees,[77] and three Australian and New Zealand ground parrots nest on the ground. All other parrots and cockatoos nest in cavities, either tree hollows or cavities dug into cliffs, banks or the ground. The use of holes in cliffs is more common in the Americas. Many species will use termite nests, possibly as it reduces the conspicuousness of the nesting site or because it creates favourable microclimates.[78] In most cases both parents will participate in the nest excavation. The length of the burrow varies with species, but is usually between 0.5–2 m in length. The nests of cockatoos are often lined with sticks, wood chips and other plant material. In the larger species of parrot and cockatoo the availability of nesting holes can be limited and this can lead to intense competition for them both within the species and between species, as well as with other bird families. The intensity of this competition can limit breeding success in some cases.[79][80] Some species are colonial, with the Burrowing Parrot nesting in colonies up to 70,000 strong.[81] Coloniality is not as common in parrots as might be expected, possibly because most species adopt old cavities rather than excavate their own.[82]

The eggs of parrots are white. In most species the female undertakes all the incubation, although incubation is shared for in cockatoos, the Blue Lorikeet, and the Vernal Hanging Parrot. The female remains in the nest for almost all of the incubation period and is fed both by the male and during short breaks. Incubation varies from 17 to 35 days, with the larger species have the longer incubation periods. The newly born young are altricial, either lacking feathers or with sparse white down. The young spend anything from three weeks to four months in the nest, depending on species, and may receive parental care for up to further months thereafter.[83]

As typical of K-selected species, the macaws and other larger parrot species have low reproductive rates. They require several years to reach maturity, produce one or very few young per year, and sometimes do not breed every year at all.

Intelligence and learning

Studies with captive birds have given insight into which birds are the most intelligent. While parrots have the distinction of being able to mimic human speech, studies with the African Grey Parrot have shown that some are able to associate words with their meanings and form simple sentences (see Alex and N'kisi). Along with crows, ravens, and jays (family Corvidae), parrots are considered the most intelligent of birds. The brain-to body size ratio of psittacines and corvines is actually comparable to that of higher primates.[84] One argument against the supposed intelligent capabilities of bird species is that birds have a relatively small cerebral cortex, which is the part of the brain considered to be the main area of intelligence in other animals. However, it seems that birds use a different part of their brain, the medio-rostral neostriatum / hyperstriatum ventrale, as the seat of their intelligence. Not surprisingly, research has shown that these species tend to have the largest hyperstriata, and Dr. Harvey J. Karten, a neuroscientist at University of California, San Diego who has studied the physiology of birds, discovered that the lower part of the avian brain is functionally similar to that in humans. Not only have parrots demonstrated intelligence through scientific testing of their language using ability, but some species of parrot such as the Kea are also highly skilled at using tools and solving puzzles.[85]

Learning in early life is apparently important to all parrots, and much of that learning is social learning. Social interactions are often practised with siblings, and in several species creches are formed with several broods, and these as well are important for learning social skills. Foraging behaviour is generally learnt from parents, and can be a very protracted affair. Supra-generalists and specialists are generally independent of their parents much quicker than partly specialised species which may have to learn skills over a long period of time as various resources become seasonally available. Play forms a large part of learning in parrots; it can be solitary, and related to motor skills, or social. Species may engage in play fights or wild flights to practice predator evasion. An absence of stimuli can retard the development of young birds, as demonstrated by a group of Vasa Parrots kept in tiny cages with domesticated chickens from the age of 3 months; at 9 months these birds still behaved in the same way as 3 month olds, but had adopted some chicken behaviour.[70] In a similar fashion captive birds in zoo collections or pets can, if deprived of stimuli, develop stereotyped behaviours and harmful behaviours like self plucking. Aviculturists working with parrots have identified the need for environmental enrichment to keep parrots stimulated.

Sound imitation and speech

Many species can imitate human speech or other sounds. A study by Irene Pepperberg suggested a high learning ability in an African Grey Parrot named Alex. Alex was trained to use words to identify objects, describe them, count them, and even answer complex questions such as "How many red squares?" with over 80% accuracy. N'kisi, another African grey, has been shown to have a vocabulary of approximately a thousand words, and has displayed an ability to invent as well as use words in context and in the correct tense.

Parrots do not have vocal cords, so sound is accomplished by expelling air across the mouth of the bifurcated trachea. Different sounds are produced by changing the depth and shape of trachea. African Grey Parrots of all subspecies are known for their superior ability to imitate sounds and human speech. This ability has made them prized as pets from ancient time to the present. In the Masnavi, a writing by Rumi of Persia, AD 1250, the author talks about an ancient method for training parrots to speak.

Although most parrot species are able to imitate, some of the Amazon parrots are generally regarded as the next-best imitators and speakers of the parrot world.

The question of why birds imitate remains open, but those that do often score very high on tests designed to measure problem solving ability. Wild African Grey Parrots have been observed imitating other birds.[86] Most other wild parrots have not been observed imitating other species.

Relationship with humans

Humans and parrots have a complicated relationship. Economically they can be beneficial to communities as sources of income from the pet trade and are highly marketable tourism draws and symbols. But some species are also economically important pests, particularly some cockatoo species in Australia. Some parrots have also benefited from human changes to the environment in some instances, and have expanded their ranges alongside agricultural activity, but many species have declined as well.

It is possible to devote careers to parrots. Zoos and aquariums employ keepers to care for and shape the behavior of parrots. Some veterinarians who specialize in avian medicine will treat parrots exclusively. Biologists study parrot populations in the wild and help to conserve wild populations. Aviculturalists breed and sell parrots for the pet trade.

Tens of millions of parrots have been removed from the wild, and parrots have been traded in greater numbers and for far longer than any other group of wild animals.[87] Many parrot species are still threatened by this trade as well as habitat loss, predation by introduced species, and hunting for food or feathers. Some parrot species are agricultural pests,[88] eating fruits, grains, and other crops, but parrots can also benefit economies through birdwatching based ecotourism.[89]

Pets

Parrots are popular as pets due to their sociable and affectionate nature, intelligence, bright colours, and ability to imitate human voices. The domesticated Budgerigar, a small parrot, is the most popular of all pet bird species. In 1992 the newspaper USA Today published that there were 11 million pet birds in the United States alone,[90] many of them parrots. Europeans kept birds matching the description of the Rose-ringed Parakeet (or called the ring-necked parrot), documented particularly in a first century account by Pliny the Elder.[91] As they have been prized for thousands of years for their beauty and ability to talk, they have also often been misunderstood. For example, author Wolfgang de Grahl discusses in his 1987 book "The Grey Parrot," that some importers allowed parrots to drink only coffee while they were being shipped by boat considering pure water to be detrimental and believing that their actions would increase survival rates during shipping. (Nowadays it is commonly accepted that the caffeine in coffee is toxic to birds).

Pet parrots may be kept in a cage or aviary; though generally, tame parrots should be allowed out regularly on a stand or gym. Depending on locality, parrots may be either wild caught or be captive bred, though in most areas without native parrots, pet parrots are captive bred.

Parrot species that are commonly kept as pets include conures, macaws, Amazons, cockatoos, African Greys, lovebirds, cockatiels, budgerigars, eclectus, Caiques, parakeets, Pionus and Poicephalus. Species vary in their temperament, noise level, talking ability, cuddliness with people, and care needs, although how a parrot has been raised usually greatly affects its personality.

Parrots can make excellent companion animals, and can form close, affectionate bonds with their owners. However they invariably require an enormous amount of attention, care and intellectual stimulation to thrive, akin to that required by a three year old child, which many people find themselves unable to provide in the long term.[92] Parrots that are bred for pets may be hand fed or otherwise accustomed to interacting with people from a young age to help ensure they will be tame and trusting. However, parrots are not low maintenance pets; they require feeding, grooming, veterinary care, training, environmental enrichment through the provision of toys, exercise, and social interaction (with other parrots or humans) for good health. Some large parrot species, including large cockatoos, Amazons, and macaws, have very long lifespans with 80 years being reported and record ages of over one hundred. Small parrots, such as lovebirds, hanging parrots, and budgies have shorter life spans of up to 15–20 years. Some parrot species can be quite loud, and many of the larger parrots can be destructive and require a very large cage, and a regular supply of new toys, branches, or other items to chew up. The intelligence of parrots means they are quick to learn tricks and other behaviors—both good and bad—that will get them what they want, such as attention or treats.

The popularity, longevity, and intelligence of many of the larger species of pet parrots has led to many of these birds being re-homed during the course of their long lifespans.

A common problem is that large parrot species which are cuddly and gentle as juveniles will mature into intelligent, complex, often demanding adults that can outlive their owners. Due to these problems, and the fact that homeless parrots are not euthanized like dogs and cats, parrot adoption centers and sanctuaries are becoming more common.

Zoos

Parrot species are found in most zoos, and a few zoos participate in breeding and conservation programs. Some zoos have organised displays of trained parrots and other birds doing tricks.

Trade

The popularity of parrots as pets has led to a thriving—and often illegal—trade in the birds, and some species are now threatened with extinction. A combination of trapping of wild birds and damage to parrot habitats makes survival difficult or even impossible for some species of parrot. Importation of wild caught parrots into the US and Europe is illegal.

The trade continues unabated in some countries. A report published in January 2007 presents a clear picture of the wild-caught parrot trade in Mexico, stating: "The majority of parrots captured in Mexico stay in the country for the domestic trade. A small percentage of this capture, 4% to 14%, is smuggled into the USA."[94] In the early 1980s an American college student who worked his way through school smuggling parrots across the Rio Grande put his contraband Mexican birds in a cage on an inflatable raft and floated with them across the international river to the U.S. side where a partner would be waiting.[95]

The scale of the problem can be seen in the Tony Silva case of 1996, in which a parrot expert and former director at Tenerife's Loro Parque (Europe's largest parrot park) was jailed in the United States for 82 months and fined $100,000 for smuggling Hyacinth Macaws.[96] (Such birds command a very high price). The case led to calls for greater protection and control over trade in the birds. Different nations have different methods of handling internal and international trade. Australia has banned the export of its native birds since 1960. The United States protects its only native parrot through its Endangered Species Act, and protects other nations' birds through its Wild Bird Conservation Act. Following years of campaigning by hundreds of NGOs and outbreaks of avian flu, in July 2007, the European Union halted the importation of all wild birds with a permanent ban on their import. Prior to an earlier temporary ban started in late October 2005, the EU was importing approximately two million live birds a year, about 90% of the international market: hundreds of thousands of these were parrots. There are no national laws protecting feral parrot populations in the U.S. Mexico has a licensing system for capturing and selling native birds (though the laws are not well enforced).

Culture

Parrots have featured in human writings, story, art, humor, religion and music for thousands of years. From the Roman poet Ovid's "The Dead Parrot"(Latin), (English) to Monty Python's Dead Parrot Sketch millennia later, parrots have existed in the consciousness of many cultures. Recent books about parrots in human culture include Parrot Culture.[97]

In ancient times and currently parrot feathers have been used in ceremonies, and for decoration. The "idea" of the parrot has been used to represent the human condition in medieval literature such as the bestiary. They also have a long history as pets.

In Polynesian legend as current in the Marquesas Islands, the hero Laka/Aka is mentioned as having undertaken a long and dangerous voyage to Aotona in what are now the Cook Islands, to obtain the highly prized feathers of a red parrot as gifts for his son and daughter. On the voyage a hundred out of his 140 rowers died of hunger on their way, but the survivors reached Aotona and captured enough parrots to fill 140 bags with their feathers.[98] By at least some versions, the feathers were plucked off living parrots without killing them.[99]

Currently parrots feature in many media. There are magazines devoted to parrots as pets, and to the conservation of parrots (PsittaScene). Fictional films include Paulie, and documentaries include The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill.

Parrots have also been considered sacred. The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped birds and often depicted parrots in their art.[100]

Parrots are used as symbols of nations and nationalism. A parrot is found on the flag of Dominica. The St. Vincent parrot is the national bird of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, a Caribbean nation.

Parrots are popular in Buddhist scripture and there are many writings about them. For example, Amitābha once changed itself into a parrot to aid in converting people. Another old story tells how after a forest caught fire, the parrot was so concerned it carried water to try and put out the flames. The ruler of heaven was so moved upon seeing the parrot's act, that he sent rain to put out the fire. In Chinese Buddhist iconography, a parrot is sometimes depicted hovering on the upper right side Guan Yin clasping a pearl or prayer beads in its beak.

Sayings about parrots colour the modern English language. The verb "parroting" can be found in the dictionary, and means "to repeat by rote." There are also clichés, such as the British saying "sick as a parrot."

Feral populations

Escaped parrots of several species have become established in the wild outside their natural ranges and in some cases outside the natural range of parrots. Among the earliest instances were pet Red Shining-parrots from Fiji which established a population on the islands of southern Tonga. These introductions were prehistoric and Red-shining Parrots were recorded in Tonga by Captain Cook in the 1770s.[67] Escapees first began breeding in cities in California, Texas and Florida in the 1950s (with unproven earlier claims dating back to the 1920s in Texas and Florida).[68] They have proved surprisingly hardy in adapting to conditions in Europe and North America. They sometimes even multiply to the point of becoming a nuisance or pest, and a threat to local ecosystems, and control measures have been used on some feral populations.[101]

Threats and conservation

A large number of parrot species are in decline, and several species are now extinct. Of the 350 or so living species of parrot 130 species are listed as near threatened or worse by the IUCN.[102] There are numerous reasons for the decline of so many species, the principal threats being habitat loss and degradation, hunting, and for certain species, wild-bird trade. Parrots are persecuted for a number of reasons; in some areas they may (or have been) hunted for food, for feathers, and as agricultural pests. For a time, Argentina offered a bounty on Monk Parakeets (an agricultural pest), resulting in hundred of thousands of birds being killed, though apparently this did not greatly affect the overall population.[103] Capture for the pet trade is a threat to many of the rarer or slower to breed species. Habitat loss or degradation, most often for agriculture, is a threat to numerous parrot species. Parrots, being cavity nesters, are vulnerable to the loss of nesting sites and to competition with introduced species for those sites. The loss of old trees is particularly a problem in some areas, particularly in Australia where suitable nesting trees may be many hundreds of years old. Many parrot species occur only on islands and are vulnerable to introduced species such as rats and cats, as they lack the appropriate anti-predator behaviours needed to deal with mammalian predators. Controlling such predators can help in maintaining or increasing the numbers of endangered species.[104] Insular species, which have small populations in restricted habitat, are also vulnerable to physical threats such as hurricanes and volcanic eruptions.

There are many active conservation groups whose goal is the conservation of wild parrot populations. One of the largest includes the World Parrot Trust,[105] an international organization. The group gives assistance to worthwhile projects as well as producing a magazine[106] and raising funds through donations and memberships, often from pet parrot owners. They state they have helped conservation work in 22 countries. On a smaller scale local parrot clubs will raise money to donate to a cause of conservation. Zoo and wildlife centers usually provide public education, to change habits that cause damage to wild populations. Recent conservation measures to conserve the habitats of some of the high-profile charismatic parrot species has also protected many of the less charismatic species living in the ecosystem.[55] A popular attraction that many zoos now employ is a feeding station for lories and lorikeets, where visitors feed small parrots with cups of liquid food. This is usually done in association with educational signs and lecture.

Several projects aimed specifically at parrot conservation have met with success. Translocation of vulnerable Kakapo, followed by intensive management and supplementary feeding, has increased the population from 50 individuals to 123.[107] In New Caledonia the Ouvea Parakeet was threatened by trapping for the pet trade and loss of habitat. Community based conservation, which eliminated the threat of poaching, has allowed the population to increase from around 600 birds in 1993 to over 2000 birds in 2009.[108]

At present the IUCN recognises 19 species of parrot as extinct since 1600 (the date used to denote modern extinctions).[109] This does not include species like the New Caledonian Lorikeet which has not been officially seen for 100 years yet is still listed as critically endangered.

Trade, export and import of all wild-caught parrots is regulated and only permitted under special licensed circumstances in countries party to CITES, the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species, that came into force in 1975 to regulate the international trade of all endangered wild caught animal and plant species. In 1975, 24 parrot species were included on Appendix I of CITES, thus prohibiting commercial international trade in these birds. Since that initial listing, continued threats from international trade have lead CITES to add an additional 32 parrot varieties to Appendix I, including nine in the last four years.[110] All the other parrot species are protected on Appendix II of CITES. In addition, individual countries may have laws to regulate trade in certain species.

References

Notes

- ^ a b c d e (EN) Black, P., González, S. (Deer Red List Authority) & Schipper, J. (Global Mammal Assessment Team) 2008, Panjabi/Prove, su IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Versione 2020.2, IUCN, 2020.

- ^ a b Peter Gravlund, Morten Meldgaard, Svante Pääbo, and Peter Arctander: Polyphyletic Origin of the Small-Bodied, High-Arctic Subspecies of Tundra Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus). MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Vol. 10, No. 2, October, pp. 151–159, 1998 ARTICLE NO. FY980525. online

- ^ a b S. A. Byun, B. F. Koop, and T. E. Reimchen: Evolution of the Dawson caribou (Rangifer tarandus dawsoni). Can. J. Zool. 80(5): 956–960 (2002). doi:10.1139/z02-062. 2002 NRC Canada. online

- ^ a b c d e Reindeer.[collegamento interrotto] Answers.com

- ^ a b c New World Deer (Capriolinae).[collegamento interrotto] Answers.com

- ^ a b "In North America and Eurasia the species has long been an important resource--in many areas the most important resource--for peoples inhabiting the northern boreal forest and tundra regions. Known human dependence on caribou/wild reindeer has a long history, beginning in the Middle Pleistocene (Banfield 1961:170; Kurtén 1968:170) and continuing to the present....The caribou/wild reindeer is thus an animal that has been a major resource for humans throughout a tremendous geographic area and across a time span of tens of thousands of years." Ernest S. Burch, Jr. The Caribou/Wild Reindeer as a Human Resource. American Antiquity, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Jul., 1972), pp. 339-368.

- ^ http://icr.arcticportal.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=142:flying-reindeer-and-santa-claus-&catid=2:feature-archive&Itemid=7

- ^ The Sámi and their reindeer — University of Texas at Austin

- ^ a b c Novak, R. M. (editor) (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Vol. 2. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. Pp. 1128-1130. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ^ Sommer R. S. and Nadachowski A.: Glacial refugia of mammals in Europe: evidence from fossil records. Mammal Rev. 2006, Volume 36, No. 4, 251-265.

- ^ Europe's last wild reindeer herds in peril

- ^ Reindeer Hunting in Iceland. International Adventure. Accessed 12 November 2010.

- ^ BBC Earth News-Reindeer herds in global decline

- ^ Vors & Boyce. Global declines of caribou and reindeer. Global Change Biology Volume 15 Issue 11, Pages 2626 - 2633, Published Online: 9 May 2009

- ^ a b Caribou at the Alaska Department of Fish & Game

- ^ a b c Aanes, R. (2007). Svalbard reindeer. Norwegian Polar Institute.

- ^ a b c Reid, F. (2006). Mammals of North America. Peterson Field Guides. ISBN 978-0-395-93596-5

- ^ "In the winter, the fleshy pads on these toes grow longer and form a tough, hornlike rim. Caribou use these large, sharp-edged hooves to dig through the snow and uncover the lichens that sustain them in winter months. Biologists call this activity "cratering" because of the crater-like cavity the caribou’s hooves leave in the snow." All About Caribou - Project Caribou

- ^ Image of reindeer cratering in snow.

- ^ Banfield AWF: The caribou. In The Unbelievable Land. Edited by: Smith IN. Ottawa: Queen's Press; 1966:25-28, cited in Knee-clicks and visual traits indicate fighting ability in eland antelopes: multiple messages and back-up signals, Jakob Bro-Jørgensen and Torben Dabelsteen, BMC Biology 2008, 6:47doi:10.1186/1741-7007-6-47

- ^ Lemmings at Hinterland Who's Who

- ^ Terrestrial Mammals of Nunavut by Ingrid Anand-Wheeler. ISBN 1-55325-035-4.

- ^ The Sun, the Moon and Firmament in Chukchi Mythology and on the Relations of Celestial Bodies and Sacrifice by Ülo Siimets at 140

- ^ Caribou Migration Monitoring by Satellite Telemetry

- ^ Eagles filmed hunting reindeer

- ^ Caribou Foes: Natural Predators in the Wilderness

- ^ Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus)

- ^ a b c Template:MSW3 Grubb

- ^ a b Cronin, M. A., M. D. Macneil, and J. C. Patton (2005). Variation in Mitochondrial DNA and Microsatellite DNA in Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in North America. Journal of Mammalogy 86(3): 495–505.

- ^ Geist, V. (2007). Defining subspecies, invalid taxonomic tools, and the fate of the woodland caribou. The Eleventh North American Caribou Workshop (2006). Rangifer, Special Issue 17: 25-28.

- ^ Gwichʼin Traditional Management Practices

- ^ Sébastien Mieusset, Le "Temps des sucres" au Québec.

- ^ Julie Ovenell-Carter, Quebec’s Carnaval is worth freezing your a** off for, theseboots.travel, 06-02-2009.

- ^ King, Irving H.(1996). The Coast Guard Expands, p. 86-91. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 155750458X.

- ^ Annual report on introduction of domestic reindeer into Alaska, Volume 14

- ^ [1]

- ^ 'Lapland Reindeer meat protected in the EU' 60°North Magazine (Accessed 19 July 2010)

- ^ European Commission PDO/PGI list (Accessed 19 July 2010)

- ^ a b c (German) Das Rentier in Europa zu den Zeiten Alexanders und Cæsars, in Mindeskrift i Anledning af Hundredeaaret for Japetus Steenstrups Fødsel, Copenhagen, 1914, pp. 1–33. Lingua sconosciuta: German (aiuto)

- ^ "Est bos cervi figura, cuius a media fronte inter aures unum cornu* exsistit excelsius magisque directum his, quae nobis nota sunt, cornibus: ab eius summo sicut palmae ramique* late diffunduntur. Eadem est feminae marisque natura, eadem forma magnitudoque cornuum." book 6, chapter 26, in Commentary on Caesar, Gallic War, Boston, Ginn and Company, 1898.

- ^ Gesner, K. (1617) Historia animalium. Liber 1, De quadrupedibus viviparis. Tiguri 1551. p. 156: De Tarando. 9. 950: De Rangifero.

- ^ Aldrovandi, U. (1621) Quadrupedum omnium bisulcorum historia. Bononiæ. Cap. 30: De Tarando - Cap. 31: De Rangifero.

- ^ Koivulehti, Jorma (2007): Saamen ja suomen 'poro'. Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 253. http://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust253/sust253_koivulehto.pdf

- ^ Flexner, Stuart Berg and Leonore Crary Hauck, eds. (1987). The Random House Dictionary of the English Language, 2nd ed. (unabridged). New York: Random House, pp. 315-16)

- ^ "The Legendary Role of Reindeer in Christmas, Jeff Westover, My Merry Christmas, accessed 27 December 2007

- ^ Coat of arms for Kuusamo.

- ^ Coat of arms for Inari.

- ^ Miyaki et al. (1998)

- ^ David M. Waterhouse, Parrots in a nutshell: The fossil record of Psittaciformes (Aves), in Historical Biology, vol. 18, n. 2, 2006, pp. 223–234, DOI:10.1080/08912960600641224.

- ^ Zoological Nomenclature Resource: Psittaciformes (Version 9.013), su zoonomen.net, www.zoonomen.net, 29 dicembre 2008.

- ^ Psittacine, in American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000. URL consultato il 9 settembre 2007 (archiviato dall'url originale il 27 agosto 2007).

- ^ Psittacine, in Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, Inc. URL consultato il 9 settembre 2007.

- ^ Christidis L, Boles WE, Systematics and Taxonomy of Australian Birds, Canberra, CSIRO Publishing, 2008, p. 200, ISBN 9780643065116.

- ^ Snyder, N; McGowan, P; Gilardi, J; & A Grajal (2000), Parrots: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, 2000-2004. Chapter 1. vii. IUCN ISBN 2-8317-0504-5. Chapter 1. vii.

- ^ a b Snyder, N; McGowan, P; Gilardi, J; & A Grajal (2000), Parrots: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, 2000-2004. Chapter 1. vii. IUCN ISBN 2-8317-0504-5. Chapter 2. page 12.

- ^ a b c T.F. Wright, Schirtzinger E. E., Matsumoto T., Eberhard J. R., Graves G. R., Sanchez J. J., Capelli S., Muller H., Scharpegge J., Chambers G. K. & Fleischer R. C., A Multilocus Molecular Phylogeny of the Parrots (Psittaciformes): Support for a Gondwanan Origin during the Cretaceous, in Mol Biol Evol, vol. 25, n. 10, 2008, pp. 2141–2156, DOI:10.1093/molbev/msn160.

- ^ Stidham T. (1998) "A lower jaw from a Cretaceous parrot" Nature 396: 29–30

- ^ Dyke GJ, Mayr G. (1999) "Did parrots exist in the Cretaceous period?" Nature 399: 317–318

- ^ Waterhouse DM. (2006) "Parrots in a nutshell: The fossil record of Psittaciformes (Aves)" Historical Biology 18(2): 227–238

- ^ Waterhouse, D.M., Lindow, B.E.K.; Zelenkov, N.; Dyke, G.J., Two new fossil parrots (Psittaciformes) from the Lower Eocene Fur Formation of Denmark, in Palaeontology, vol. 51, 2008, pp. 575–582, DOI:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00777.x.

- ^ Dyke GJ, Cooper JH (2000) "A new psittaciform bird from the London clay (Lower Eocene) of England" Palaeontology 43: 271–285

- ^ a b c RS de Kloet, de Kloet SR, The evolution of the spindlin gene in birds: Sequence analysis of an intron of the spindlin W and Z gene reveals four major divisions of the Psittaciformes., in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 36, n. 3, 2005, pp. 706–721, DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.03.013.

- ^ a b M Tokita, Kiyoshi T and Armstrong KN, Evolution of craniofacial novelty in parrots through developmental modularity and heterochrony., in Evolution & Development, vol. 9, n. 6, 2007, pp. 590–601, DOI:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2007.00199.x.

- ^ Edward H. Burtt, Max R. Schroeder, Lauren A. Smith, Jenna E. Sroka, Kevin J. McGraw (2010): Colourful parrot feathers resist bacterial degradation, Biology Letters, The Royal Society, doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.0716.

- ^ Forshaw, Joseph M. & Cooper, William T. (1978): Parrots of the World (2nd ed). Landsdowne Editions, Melbourne Australia ISBN 0-7018-0690-7

- ^ Y. Miyaki, Parrot evolution and paleogeographical events: Mitochondrial DNA evidence (PDF), in Molecular Biology and Evolution, vol. 15, n. 5, 1998, pp. 544–551.

- ^ a b Steadman D, (2006). Extinction and Biogeography in Tropical Pacific Birds, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-77142-7 pp.342–351

- ^ a b Butler C (2005) "Feral Parrots in the Continental United States and United Kingdom: Past, Present, and Future" Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery 19(2): 142–149

- ^ Daniel Sol, Santos, David M. ; Feria, Elías & Jordi Clavell, Habitat Selection by the Monk Parakeet during Colonization of a New Area in Spain, in Condor, vol. 99, n. 1, 1997, pp. 39–46, DOI:10.2307/1370222.

- ^ a b c d e f Collar N (1997) "Family Psittacidae (Parrots)" in Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 4; Sandgrouse to Cuckoos (eds del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J) Lynx Edicions:Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-22-9

- ^ Diamond, J (1999). "Evolutionary biology: Dirty eating for healthy living" Nature 400(6740): 120–121

- ^ Gartrell B, Jones S, Brereton R & Astheimer L (2000) "Morphological Adaptations to Nectarivory of the Alimentary Tract of the Swift Parrot Lathamus discolor". Emu 100(4) 274–279

- ^ Kea – Mountain Parrot, NHNZ. (1 hour documentary)