Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox

| Rinoceronte di Giava | |

|---|---|

Rhinoceros sondaicus | |

| Stato di conservazione | |

Critico[1] | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Dominio | Eukaryota |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Ordine | Perissodactyla |

| Famiglia | Rhinocerotidae |

| Genere | Rhinoceros |

| Specie | R. sondaicus |

| Nomenclatura binomiale | |

| Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmarest, 1822 | |

| Areale | |

| |

Il rinoceronte di Giava (Rhinoceros sondaicus), noto anche come rinoceronte della Sonda, è un membro molto raro della famiglia dei Rinocerotidi e una delle cinque specie esistenti di rinoceronte. Appartiene allo stesso genere del rinoceronte indiano, e come questo possiede una pelle ricoperta da pieghe che fa pensare a un'armatura, ma con una lunghezza di 3,1-2,2 m e un'altezza di 1,4-1,7 m, è più piccolo di quest'ultimo (in effetti le sue dimensioni ricordano più da vicino quelle del rinoceronte nero del genere Diceros). Il suo corno misura solitamente meno di 25 cm di lunghezza, ed è quindi più piccolo di quello delle altre specie di rinoceronte. Solo i maschi adulti possiedono corni; le femmine ne sono completamente prive.

Un tempo il più diffuso tra i rinoceronti asiatici, il rinoceronte di Giava occupava un areale che dalle isole di Giava e di Sumatra, attraverso il Sud-est asiatico, arrivava all'India e alla Cina. La specie è gravemente minacciata: ne rimane un'unica popolazione nota in natura e nessun individuo in cattività. Si tratta forse del grande mammifero più raro del mondo[2], con una popolazione di appena 58-61 esemplari nel parco nazionale di Ujung Kulon nell'estremità occidentale di Giava in Indonesia[3]. Una seconda popolazione nel parco nazionale di Cat Tien in Vietnam è stata dichiarata estinta nel 2011[4]. Il declino del rinoceronte di Giava viene attribuito al bracconaggio, soprattutto per il corno, particolarmente richiesto nella medicina tradizionale cinese, che può raggiungere i 30.000 $ al kg sul mercato nero[2]. Quando nel suo areale divenne più consistente la presenza degli europei, anche la caccia grossa si trasformò in una seria minaccia. Anche la distruzione dell'habitat, specialmente a causa delle guerre, quali la guerra del Vietnam, nel Sud-est asiatico, ha contribuito al declino della specie e ne ha impedito il recupero[5]. L'areale attuale ricade interamente entro un'area rigorosamente protetta, ma i rinoceronti sono ancora alla mercé dei bracconieri, delle malattie e della perdita della diversità genetica dovuta alla depressione endogamica.

Il rinoceronte di Giava può vivere in natura fino a circa 30-45 anni. In passato popolava foreste pluviali di pianura, distese erbose umide e vaste pianure alluvionali. Conduce vita prevalentemente solitaria, fatta eccezione per l'epoca del corteggiamento e dell'allevamento dei piccoli, anche se più esemplari possono aggregarsi occasionalmente nei pressi di pozze di fango e affioramenti di sale. Escluso l'uomo, gli adulti non hanno predatori nel loro areale. Il rinoceronte di Giava generalmente evita gli esseri umani, ma può attaccare quando si sente minacciato. Solo raramente gli scienziati e i conservazionisti riescono a studiare l'animale direttamente, data la sua estrema rarità e il pericolo di interferire con una specie così minacciata. I ricercatori si basano sulle trappole fotografiche e sui campioni fecali per valutare la salute e il comportamento. Di conseguenza, il rinoceronte di Giava è la specie di rinoceronte meno studiata. Le immagini di due esemplari adulti con i loro piccoli sono stati riprese con una telecamera attivata dal movimento rilasciata il 28 febbraio 2011 dal WWF e dall'Autorità dei Parchi Nazionali dell'Indonesia, provando così che la specie si sta ancora riproducendo in natura[6]. Nell'aprile 2012, l'Autorità dei Parchi Nazionali ha rilasciato un video che mostra 35 esemplari diversi di rinoceronte di Giava, comprese coppie madre-piccolo e adulti in corteggiamento[7].

Tassonomia ed etimologia

I naturalisti occidentali entrarono per la prima volta in contatto con il rinoceronte di Giava nel 1787, quando a Giava ne vennero abbattuti due esemplari. I loro crani furono inviati al celebre naturalista olandese Petrus Camper, che morì nel 1789 prima di essere riuscito a pubblicare uno studio nel quale il rinoceronte di Giava veniva riconosciuto come una specie a sé. Un altro rinoceronte di Giava venne abbattuto sull'isola di Sumatra da Alfred Duvaucel, che inviò l'esemplare al suo patrigno Georges Cuvier, il famoso scienziato francese. Cuvier riconobbe l'animale come una specie distinta nel 1822, e nello stesso anno venne battezzato da Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest Rhinoceros sondaicus. Si trattava dell'ultima specie di rinoceronte ad essere identificata[8]. Desmarest in un primo momento indicò come luogo di provenienza dell'animale Sumatra, ma in seguito corresse quanto scritto sostenendo che l'esemplare proveniva da Giava[9].

Il nome del genere Rhinoceros, al quale appartiene anche il rinoceronte indiano, deriva dal greco antico ῥίς (rhis), che significa «naso», e κέρας (ceras), che significa «corno»; sondaicus deriva da Sonda, la regione biogeografica che comprende le isole di Sumatra, Giava, Borneo e le isole minori circostanti. Il rinoceronte di Giava è noto anche come rinoceronte unicorne minore (per distinguerlo dal rinoceronte unicorne maggiore, altro nome del rinoceronte indiano)[10].

Delle tre diverse sottospecie, ne sopravvive solamente una:

- R. s. sondaicus, la sottospecie nominale, nota come rinoceronte di Giava indonesiano, originaria di Giava e Sumatra. L'unica popolazione rimasta, costituita da non più di 50 esemplari allo stato selvatico, è confinata nel parco nazionale di Ujung Kulon nell'estremità occidentale dell'isola di Giava. Un ricercatore ha ipotizzato che i rinoceronti di Giava che un tempo erano diffusi a Sumatra appartenessero a una sottospecie distinta, R. s. floweri, ma questa teoria non è stata ampiamente riconosciuta[11][12];

- R. s. annamiticus, nota come rinoceronte di Giava vietnamita o rinoceronte del Vietnam, originaria di Cina meridionale, Vietnam, Cambogia, Laos, Thailandia e Malesia. Deve l'epiteto annamiticus alla Cordigliera Annamita, una catena montuosa del Sud-est asiatico che ricade entro i confini dell'areale storico della sottospecie. Nel 2006, un'unica popolazione, stimata a meno di 12 esemplari rimasti, viveva ancora in una zona di foresta di pianura del parco nazionale di Cat Tien in Vietnam. Le analisi genetiche suggerirono che questa sottospecie e il rinoceronte di Giava indonesiano si fossero separati in un periodo compreso tra 300.000 anni fa e 2 milioni di anni fa[11][12]. L'ultimo esemplare di questa popolazione è stato abbattuto da un bracconiere nel 2010[13].

- R. s. inermis, noto come rinoceronte di Giava indiano, originario della regione compresa tra Bengala e Myanmar, ma probabilmente scomparsa prima del 1925[14]. L'epiteto specifico inermis significa «disarmato», in quanto la caratteristica principale di questa sottospecie era il corno particolarmente piccolo nei maschi e la sua evidente assenza nelle femmine. L'olotipo di questa sottospecie era una femmina priva di corno. La situazione politica del Myanmar ha impedito lo svolgersi di sopralluoghi per valutare lo status della specie nel Paese, ma una sua sopravvivenza sembra molto improbabile[15][16][17].

Evoluzione

Si ritiene che i rinoceronti ancestrali si siano separati per la prima volta dagli altri perissodattili in the Early Eocene. Mitochondrial DNA comparison suggests the ancestors of modern rhinos split from the ancestors of Equidae around 50 million years ago.[18] The extant family, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia, and the ancestors of the extant rhino species dispersed from Asia beginning in the Miocene.[19]

The Indian and Sunda rhinoceros, the only members of the genus Rhinoceros, first appear in the fossil record in Asia around 1.6 million–3.3 million years ago. Molecular estimates, however, suggest the two species diverged from each other much earlier, around 11.7 million years ago.[20] Although belonging to the type genus, the Indian and Sunda rhinoceroses are not believed to be closely related to other rhino species. Different studies have hypothesized that they may be closely related to the extinct Gaindatherium or Punjabitherium. A detailed cladistic analysis of the Rhinocerotidae placed Rhinoceros and the extinct Punjabitherium in a clade with Dicerorhinus, the Sumatran rhino. Other studies have suggested the Sumatran rhinoceros is more closely related to the two African species.[21] The Sumatran rhino may have diverged from the other Asian rhinos 15 million years ago,[19] or as far back as 25.9 million years ago based on mitochondrial data.[20]

Description

The Sunda rhino is smaller than the Indian rhinoceros, and is close in size to the black rhinoceros. It is the largest animal in Java and the second-largest animal in Indonesia after the Asian elephant. The body length of the Sunda rhino (including its head) can be up to 2 fino a 4 m (6,6 fino a 13,1 ft), and it can reach a height of 1,4–1,7 m (4,6–5,6 ft). Adults are variously reported to weigh between 900 e 2,300 kg (1 984,16 e 5,07 lb), although a study to collect accurate measurements of the animals has never been conducted and is not a priority because of their extreme conservation status.[22] No substantial size difference is seen between genders, but females may be slightly bigger. The rhinos in Vietnam appeared to be significantly smaller than those in Java, based on studies of photographic evidence and measurements of their footprints.[23]

Like the Indian rhino, the Sunda rhinoceros has a single horn (the other extant species have two horns). Its horn is the smallest of all extant rhinos, usually less than 20 cm (7,9 in) with the longest recorded only 27 cm (11 in). Only males have horns. Female Sunda rhinos are the only extant rhinos that remain hornless into adulthood, though they may develop a tiny bump of an inch or two in height. The Sunda rhinoceros does not appear to often use its horn for fighting, but instead uses it to scrape mud away in wallows, to pull down plants for eating, and to open paths through thick vegetation. Similar to the other browsing species of rhino (the black, Sumatran, and Indian), the Sunda rhino has long, pointed, upper lips which help in grabbing food. Its lower incisors are long and sharp; when the Sunda rhino fights, it uses these teeth. Behind the incisors, two rows of six low-crowned molars are used for chewing coarse plants. Like all rhinos, the Sunda rhino smells and hears well, but has very poor vision. They are estimated to live for 30 to 45 years.[23]

Its hairless, splotchy gray or gray-brown skin falls in folds to the shoulder, back and rump. The skin has a natural mosaic pattern, which lends the rhino an armored appearance. The neck folds of the Sunda rhinoceros are smaller than those of the Indian rhinoceros, but still form a saddle shape over the shoulder. Because of the risks of interfering with such an endangered species, however, the Sunda rhinoceros is primarily studied through fecal sampling and camera traps. They are rarely encountered, observed or measured directly.[24]

Distribution and habitat

Even the most optimistic estimate suggests fewer than 100 Sunda rhinos remain in the wild. They are considered one of the most endangered species in the world.[25] The Sunda rhinoceros is known to survive in only one place, the Ujung Kulon National Park on the western tip of Java.[12][26]

The animal was once widespread from Assam and Bengal (where their range would have overlapped with both the Sumatran and Indian rhinos)[17] eastward to Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, and southwards to the Malay Peninsula and the islands of Sumatra, Java, and possibly Borneo.[27] The Sunda rhino primarily inhabits dense, lowland rain forests, grasslands, and reed beds with abundant rivers, large floodplains, or wet areas with many mud wallows. Although it historically preferred low-lying areas, the subspecies in Vietnam was pushed onto much higher ground (up to 2,000 m or 6,561 ft), probably because of human encroachment and poaching.[15]

The range of the Sunda rhinoceros has been shrinking for at least 3,000 years. Starting around 1000 BC, the northern range of the rhinoceros extended into China, but began moving southward at roughly 0,5 km (0,31 mi) per year, as human settlements increased in the region.[28] It likely became locally extinct in India in the first decade of the 20th century.[17] The Sunda rhino was hunted to extinction on the Malay Peninsula by 1932.[29] The last ones on Sumatra died out during World War II. They were extinct from Chittagong and the Sunderbans by the middle of the 20th century. By the end of the Vietnam War, the Vietnamese rhinoceros was believed extinct across all of mainland Asia. Local hunters and woodcutters in Cambodia claim to have seen Sunda rhinos in the Cardamom Mountains, but surveys of the area have failed to find any evidence of them.[30] In the late 1980s, a small population was found in the Cat Tien area of Vietnam. However, the last individual of that population was shot in 2010.[31] A population may have existed on the island of Borneo, as well, though these specimens could have been the Sumatran rhinoceros, a small population of which still lives there.[27]

Behavior

The Sunda rhinoceros is a solitary animal with the exception of breeding pairs and mothers with calves. They sometimes congregate in small groups at salt licks and mud wallows. Wallowing in mud is a common behavior for all rhinos; the activity allows them to maintain cool body temperatures and helps prevent disease and parasite infestation. The Sunda rhinoceros does not generally dig its own mud wallows, preferring to use other animals' wallows or naturally occurring pits, which it will use its horn to enlarge. Salt licks are also very important because of the essential nutrients the rhino receives from the salt. Male home ranges are larger at 12–20 km (7,5–12,4 mi)²) compared to the female, which are around 3–14 km (1,9–8,7 mi)²). Male territories overlap each other less than those of the female. It is not known if there are territorial fights.[32]

Males mark their territories with dung piles and by urine spraying. Scrapes made by the feet in the ground and twisted saplings also seem to be used for communication. Members of other rhino species have a peculiar habit of defecating in massive rhino dung piles and then scraping their back feet in the dung. The Sumatran and Sunda rhinos, while defecating in piles, do not engage in the scraping. This adaptation in behavior is thought to be ecological; in the wet forests of Java and Sumatra, the method may not be useful for spreading odors.[32]

The Sunda rhino is much less vocal than the Sumatran; very few Sunda rhino vocalizations have ever been recorded. Adults have no known predators other than humans. The species, particularly in Vietnam, is skittish and retreats into dense forests whenever humans are near. Though a valuable trait from a survival standpoint, it has made the rhinos difficult to study.[5] Nevertheless, when humans approach too closely, the Sunda rhino becomes aggressive and will attack, stabbing with the incisors of its lower jaw while thrusting upward with its head.[32] Its comparatively antisocial behavior may be a recent adaptation to population stresses; historical evidence suggests they, like other rhinos, were once more gregarious.[12]

Diet

The Sunda rhinoceros is herbivorous, eating diverse plant species, especially their shoots, twigs, young foliage and fallen fruit. Most of the plants favored by the species grow in sunny areas in forest clearings, shrubland and other vegetation types with no large trees. The rhino knocks down saplings to reach its food and grabs it with its prehensile upper lip. It is the most adaptable feeder of all the rhino species. Currently, it is a pure browser, but probably once both browsed and grazed in its historical range. The rhino eats an estimated 50 kg (110 lb) of food daily. Like the Sumatran rhino, it needs salt in its diet. The salt licks common in its historical range do not exist in Ujung Kulon, but the rhinos there have been observed drinking seawater, likely for the same nutritional need.[32]

Conservation

The main factor in the continued decline of the Sunda rhinoceros population has been poaching for horns, a problem that affects all rhino species. The horns have been a traded commodity for more than 2,000 years in China, where they are believed to have healing properties. Historically, the rhinoceros' hide was used to make armor for Chinese soldiers, and some local tribes in Vietnam believed the hide could be used to make an antidote for snake venom.[33] Because the rhinoceros' range encompasses many areas of poverty, it has been difficult to convince local people not to kill a seemingly (otherwise) useless animal which could be sold for a large sum of money.[28] When the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora first went into effect in 1975, the Sunda rhinoceros was placed under complete Appendix 1 protection; all international trade in the Sunda rhinoceros and products derived from it is illegal.[34] Surveys of the rhinoceros horn black market have determined that Asian rhinoceros horn fetches a price as high as $30,000 per kg, three times the value of African rhinoceros horn.[2]31

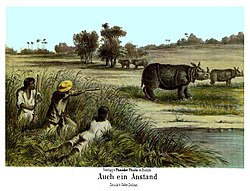

As with many types Asian and African megafauna, the Sunda rhino was relentlessly hunted by trophy and big-game hunters for decades following the arrival of Europeans in its range. The rhinos being easy targets, this was as severe a contributor to its decline as was poaching for its horns. Such was the toll of big-game hunting that by the time the rhino's plight was made known to the world, only the Javan and the (then unknown) Vietnamese populations remained.

Loss of habitat because of agriculture has also contributed to its decline, though this is no longer as significant a factor because the rhinoceros only lives in one nationally protected park. Deteriorating habitats have hindered the recovery of rhino populations that fell victim to poaching. Even with all the conservation efforts, the prospects for their survival are grim. Because the population is restricted to one small area, they are very susceptible to disease and inbreeding depression. Conservation geneticists estimate a population of 100 rhinos would be needed to preserve the genetic diversity of this conservation-reliant species.[26]

Ujung Kulon

The Ujung Kulon peninsula of Java was devastated by the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. The Sunda rhinoceros recolonized the peninsula after the event, but humans never returned in large numbers, thus creating a haven.[26] In 1931, as the Sunda rhinoceros was on the brink of extinction in Sumatra, the government of the Dutch Indies declared the rhino a legally protected species, which it has remained ever since.[15] A census of the rhinos in Ujung Kulon was first conducted in 1967; only 25 animals were recorded. By 1980, that population had doubled, and has remained steady, at about 50, ever since. Although the rhinos in Ujung Kulon have no natural predators, they have to compete for scarce resources with wild cattle, which may keep their numbers below the peninsula's carrying capacity.[35] Ujung Kulon is managed by the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry.[15] Evidence of at least four baby rhinos was discovered in 2006, the most ever documented for the species.[36]

In March 2011, hidden-camera video was published showing adults and juveniles, indicating recent matings and breeding.[37] During the period from January to October 2011, the cameras had captured images of 35 rhinos. As of December 2011, a rhino breeding sanctuary in an area of 38,000 hectares is being finalized to help reach the target of 70 to 80 Sunda rhinos by 2015.[38]

In April 2012, the WWF and International Rhino Foundation added 120 video cameras to the existing 40 to better monitor rhino movements and judge the size of the animals' population. A recent survey has found far fewer females than males. Only four females among 17 rhinos were recorded in the eastern half of Ujung Kulon, which is a potential setback in efforts to save the species.[39]

With Ujung Kulon as the last resort of this species, all the Sunda rhinos are in one ___location, an advantage over the Sumatran rhino which is dispersed in different, unconnected areas. However, this may also be disadvantageous to the Sunda rhino population, because any catastrophic diseases or tsunamis could wipe them all out at once. Poaching for their horns is no longer as serious a threat as in the past, due to stricter international regulations on rhino horn, active protection efforts by local authorities, the rhinos' elusiveness and Ujung Kulon's remoteness. However, there are still obstacles to the species recovery. In 2012, the Asian Rhino Project was working out the best eradication programme for the arenga palm, which was blanketing the park and crowding out the rhinos' food sources. The banteng cattle also compete with the rhinos for food, so the authorities were considering plans to fence off the western part of the park to keep the livestock out.[40]

Cat Tien

Once widespread in Southeast Asia, the Sunda rhinoceros was presumed extinct in Vietnam in the mid-1970s, at the end of the Vietnam War. The combat wrought havoc on the ecosystems of the region through use of napalm, extensive defoliation from Agent Orange, aerial bombing, use of landmines, and overhunting by local poachers.[33]

In 1988, the assumption of the subspecies' extinction was challenged when a hunter shot an adult female, proving the species had somehow survived the war. In 1989, scientists surveyed Vietnam's southern forests to search for evidence of other survivors. Fresh tracks belonging to up to 15 rhinos were found along the Dong Nai River.[41] Largely because of the rhinoceros, the region they inhabited became part of the Cat Tien National Park in 1992.[33]

By the early 2000s, their population was feared to have declined past the point of recovery in Vietnam, with some conservationists estimating as few as three to eight rhinos, and possibly no males, survived.[26][36] Conservationists debated whether or not the Vietnamese rhinoceros had any chance of survival, with some arguing that rhinos from Indonesia should be introduced in an attempt to save the population, with others arguing that the population could recover.[5][42]

Genetic analysis of dung samples collected in Cat Tien National Park in a survey from October 2009 to March 2010 showed only a single individual Sunda rhinoceros remained in the park. In early May 2010, the body of a Sunda rhino was found in the park. The animal had been shot and its horn removed by poachers.[43] In October 2011, the International Rhino Foundation confirmed the Sunda rhinoceros was extinct in Vietnam, leaving only the rhinos in Ujung Kulon.[4][13][44]

In captivity

A Sunda rhinoceros has not been exhibited in a zoo for over a century. In the 19th century, at least four rhinos were exhibited in Adelaide, Calcutta, and London. At least 22 Sunda rhinos have been documented as having been kept in captivity; the true number is possibly greater, as the species was sometimes confused with the Indian rhinoceros.[45]

The Sunda rhinoceros never fared well in captivity. The oldest lived to be 20, about half the age that the rhinos can reach in the wild. No records are known of a captive rhino giving birth. The last captive Sunda rhino died at the Adelaide Zoo in Australia in 1907, where the species was so little known that it had been exhibited as an Indian rhinoceros.[23]

[46][47][48]Errore nelle note: </ref> di chiusura mancante per il marcatore <ref>[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][44][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][41][42][43]<ref name="Garten">

L.C. Rookmaaker, A Javan rhinoceros, Rhinoceros sondaicus, in Bali in 1839, in Zoologische Garten, vol. 75, n. 2, 2005, pp. 129–131.

Note

- ^ (EN) van Strien et al. 2008, BlackPanther2013/Sandbox, su IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Versione 2020.2, IUCN, 2020.

- ^ a b c Eric Dinerstein, The Return of the Unicorns; The Natural History and Conservation of the Greater One-Horned Rhinoceros, New York, Columbia University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-231-08450-1.

- ^ Rhino population figures, su savetherhino.org. URL consultato il 24 maggio 2015.

- ^ a b Mark Kinver, Javan rhino 'now extinct in Vietnam', su BBC News, 24 ottobre 2011. URL consultato il 19 giugno 2012.

- ^ a b c C. Santiapillai, Javan rhinoceros in Vietnam, in Pachyderm, vol. 15, 1992, pp. 25-27.

- ^ WWF – Critically Endangered Javan Rhinos and Calves Captured on Video. wwf.panda.org. Retrieved on 24 February 2012.

- ^ New video documents nearly all the world's remaining Javan rhinos. Mongabay.com. Retrieved on 2012-05-01.

- ^ Kees Rookmaaker, First sightings of Asian rhinos, in Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, Londra, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, p. 52.

- ^ L. C. Rookmaaker, The type locality of the Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus Desmarest, 1822) (PDF), in Zeitschrift fur Saugetierkunde, 47 (6), 1982, pp. 381-382.

- ^ Javan Rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus), su rhinos-irf.org, International Rhino Foundation. URL consultato il 17 dicembre 2014 (archiviato dall'url originale il 22 luglio 2011).

- ^ a b van Strien, N.J., Steinmetz, R., Manullang, B., Sectionov, Han, K.H., Isnan, W., Rookmaaker, K., Sumardja, E., Khan, M.K.M. & Ellis, S. 2008. Rhinoceros sondaicus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2

- ^ a b c d Prithiviraj Fernando, Gert Polet, Nazir Foead, Linda S. Ng, Jennifer Pastorini and Don J. Melnick, Genetic diversity, phylogeny and conservation of the Javan rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), in Conservation Genetics, 7 (3), Giugno 2006, pp. 439-448, DOI:10.1007/s10592-006-9139-4.

- ^ a b Hanna Gersmann, Javan rhino driven to extinction in Vietnam, conservationists say, in The Guardian, 25 ottobre 2011. URL consultato il 25 ottobre 2011.

- ^ Old Rhino Accounts in Sundarbans. Scribd.com (2009-09-02). Retrieved on 2012-02-24.

- ^ a b c d Thomas J. Foose and Nico van Strien, Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 1997, ISBN 2-8317-0336-0.

- ^ Kees Rookmaaker, Records of the Sundarbans Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus inermis) in India and Bangladesh, in Pachyderm, vol. 24, 1997, pp. 37-45.

- ^ a b c L. C. Rookmaaker, Historical records of the Javan rhinoceros in North-East India, in Newsletter of the Rhino Foundation of Nature in North-East India (4), vol. 4, Giugno 2002, pp. 11-12.

- ^ Errore nelle note: Errore nell'uso del marcatore

<ref>: non è stato indicato alcun testo per il marcatoreDNA - ^ a b c Frédéric Lacombat, The evolution of the rhinoceros, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, pp. 46–49.

- ^ a b c C. Tougard, Phylogenetic relationships of the five extant rhinoceros species (Rhinocerotidae, Perissodactyla) based on mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12s rRNA genes (PDF), in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, vol. 19, n. 1, 2001, pp. 34–44, DOI:10.1006/mpev.2000.0903.

- ^ a b Esperanza Cerdeño, Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla) (PDF), in Novitates, n. 3143, American Museum of Natural History, 1995. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ a b images and movies of the Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus), ARKive

- ^ a b c d Nico van Strien, Javan Rhinoceros, in Fulconis, R. (a cura di), Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6, London, European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2005, pp. 75–79.

- ^ a b Margaret Munro, Their trail is warm: Scientists are studying elusive rhinos by analyzing their feces, in National Post, May 10, 2002.

- ^ a b Top 10 most endangered species in the world, in Daily Telegraph, 4 January 2010. URL consultato il 19 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Mark Derr, Racing to Know the Rarest of Rhinos, Before It's Too Late, in The New York Times, July 11, 2006. URL consultato il 14 ottobre 2007.

- ^ a b c Cranbook, Earl of, The Javan Rhinoceros Rhinoceros Sondaicus in Borneo (PDF), in The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, vol. 55, n. 1, University of Singapore, 2007, pp. 217–220. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ a b c Richard T. Corlett, The Impact of Hunting on the Mammalian Fauna of Tropical Asian Forests, in Biotropica, vol. 39, n. 3, 2007, pp. 202–303, DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7429.2007.00271.x.

- ^ a b Faezah Ismail, On the horns of a dilemma, in New Straits Times, June 9, 1998.

- ^ a b J.C. Daltry, Cardamom Mountains biodiversity survey, Cambridge, Fauna and Flora International, 2000, ISBN 190370300X.

- ^ http://vietnam.panda.org/en/newsroom/news/?202075/Inadequate-protection-causes-Javan-rhino-extinction-in-Vietnam

- ^ a b c d e M. Hutchins, Rhinoceros behaviour: implications for captive management and conservation, in International Zoo Yearbook, vol. 40, n. 1, Zoological Society of London, 2006, pp. 150–173, DOI:10.1111/j.1748-1090.2006.00150.x.

- ^ a b c d Bruce Stanley, Scientists Find Surviving Members of Rhino Species, June 22, 1993.

- ^ a b R. Emslie, African Rhino. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 1999, ISBN 2-8317-0502-9.

- ^ a b Richel Dursin, Environment-Indonesia: Javan Rhinoceros Remains At High Risk, in Inter Press Service, January 16, 2001.

- ^ a b c Lucy Williamson, Baby boom for near-extinct rhino, in BBC News, September 1, 2006. URL consultato il 16 ottobre 2007.

- ^ a b Rare rhinos captured on camera in Indonesia, video, ABC News Online, 1 March 2011 (Expires: 30 May 2011)

- ^ a b Cameras show 35 rare rhinos in Indonesia: official, PhysOrg, December 30, 2011

- ^ a b Cameras Used to Help Save Endangered Javan Rhino, in Jakarta Globe, April 17, 2012.

- ^ Sunda rhino clings to survival in last forest stronghold, in The Guardian, September 7, 2012.

- ^ a b Paul Raeburn, World's Rarest Rhinos Found In War-Ravaged Region of Vietnam, April 24, 1989.

- ^ a b Javan Rhinoceros; Rare, mysterious, and highly threatened, in World Wildlife Fund, March 28, 2007. URL consultato il 4 novembre 2007.

- ^ a b Rare Javan rhino found dead in Vietnam, su wwf.panda.org, WWF, 10 May 2010.

- ^ a b WWF – Inadequate protection causes Javan rhino extinction in Vietnam. Wwf.panda.org (2011-10-25). Retrieved on 2012-02-24.

- ^ Errore nelle note: Errore nell'uso del marcatore

<ref>: non è stato indicato alcun testo per il marcatoreGarten - ^ Template:MSW3 Perissodactyla

- ^ Template:IUCN2008

- ^ Map derived from range map in Foose and Van Strien (1997). This map does not include the possible population in Borneo described by Cranbook and Piper (2007).

Taiwan, in cinese (romanizzazione Wade-Giles) T’ai-wan o (pinyin) Taiwan, in portoghese Formosa, è un'isola situata circa 161 km al largo delle coste sud-orientali della Cina continentale. Misura circa 394 km di lunghezza (nord-sud) e 144 km di larghezza nel suo punto più largo. La città più grande, Taipei, è sede del governo della Repubblica di Cina (ROC; Cina Nazionalista). Oltre all'isola principale, il governo della ROC ha la giurisdizione su 22 isole del gruppo di Taiwan e su 64 isole dell'arcipelago delle Pescadores, a ovest.

Taiwan è bagnata a nord dal mar Cinese Orientale, che la separa dalle isole Ryukyu, da Okinawa e dal Giappone vero e proprio; a est dall'oceano Pacifico; a sud dal canale di Bashi, che la separa dalle Filippine; e a ovest dallo stretto di Taiwan (o di Formosa), che la separa dalla Cina continentale.

L'Azerbaigian, noto anche come Azerbaidzhan, ufficialmente Repubblica dell'Azerbaigian, in azero Azärbayjan Respublikasi, è un Paese della Transcaucasia orientale. Occupando un'area che costeggia i versanti meridionali della catena del Caucaso, confina a nord con la Russia, a est con il mar Caspio, a sud con l'Iran, a ovest con l'Armenia e a nord-ovest con la Georgia. L'exclave del Naxçıvan (Nakhichevan) è localizzata a sud-ovest dell'Azerbaigian vero e proprio, e confina con Armenia, Iran e Turchia. L'Azerbaigian comprende entro i suoi confini l'enclave a prevalenza armena del Nagorno-Karabakh, che dal 1988 è stata al centro di un intenso conflitto tra Azerbaigian e Armenia. La sua capitale è l'antica città di Baku (Bakı), che ospita il miglior porto del mar Caspio.

Oltre al suo territorio variegato e spesso straordinariamente bello, l'Azerbaigian offre un mix di tradizioni e di sviluppo moderno. Il fiero e antico popolo delle sue aree più remote conserva molte tradizioni popolari caratteristiche, ma la vita dei suoi abitanti è stata molto influenzata dalla crescente modernizzazione caratterizzata dall'industrializzazione, dallo sviluppo delle risorse energetiche e dalla crescita delle città, nelle quali attualmente vive più della metà della popolazione. L'industria domina l'economia, e attività più diversificate hanno rimpiazzato lo sfruttamento del petrolio, di cui l'Azerbaigian è stato il principale produttore al mondo agli inizi del XX secolo. Eleganti cavalli e caviale continuano ad essere alcune delle esportazioni tradizionali più caratteristiche della repubblica.

L'Azerbaigian fu una nazione indipendente dal 1918 al 1920, ma venne successivamente incorporato nell'Unione Sovietica. Diventò una repubblica costituente (unione) nel 1936. L'Azerbaigian dichiarò la sovranità il 23 settembre 1989 e l'indipendenza il 30 agosto 1991.