Utente:BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/kakapo

| Canguro rosso | |

|---|---|

Maschio allo zoo di Melbourne  Femmina allo zoo di Nashville | |

| Stato di conservazione | |

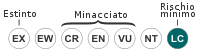

Rischio minimo[1] | |

| Classificazione scientifica | |

| Dominio | Eukaryota |

| Regno | Animalia |

| Sottoregno | Eumetazoa |

| Superphylum | Deuterostomia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Subphylum | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum | Gnathostomata |

| Superclasse | Tetrapoda |

| Classe | Mammalia |

| Sottoclasse | Theria |

| Infraclasse | Metatheria |

| Superordine | Australidelphia |

| Ordine | Diprotodontia |

| Sottordine | Macropodiformes |

| Famiglia | Macropodidae |

| Genere | Macropus |

| Sottogenere | Osphranter |

| Specie | M. rufus |

| Nomenclatura binomiale | |

| Macropus rufus (Desmarest, 1822) | |

| Sinonimi | |

| Areale | |

| |

Il canguro rosso (Macropus rufus (Desmarest, 1822)) è il più grande tra tutti i canguri, oltre ad essere il più grosso mammifero terrestre originario dell'Australia e il più grande marsupiale vivente. È diffuso in gran parte dell'Australia continentale: evita solamente le più fertili aree del sud, la costa orientale e le foreste pluviali del nord.

Descrizione

È un canguro molto grande, con lunghe orecchie appuntite e muso squadrato. I maschi sono ricoperti da una corta pelliccia bruno-rossastra, che sbiadisce fino a divenire di un beige chiaro sulle parti inferiori e sugli arti. Le femmine sono più piccole dei maschi e presentano un manto di colore grigio-azzurro con sfumature marroni, grigio chiaro sul ventre, anche se le femmine che vivono nelle regioni aride mostrano una colorazione più simile a quella dei maschi. Possiede arti anteriori dotati di piccole unghie, arti posteriori muscolosi usati per saltare e una coda robusta che viene spesso utilizzata come un treppiede quando l'animale è in posizione di riposo. Le zampe del canguro rosso funzionano un po' come una fascia elastica, con il tendine di Achille che si allunga quando l'animale scende e rilascia la sua energia per spingerlo in alto e in avanti, consentendogli la sua caratteristica andatura a balzi. Così facendo, i maschi possono coprire anche 8-9 m di lunghezza e 1,8-3 m di altezza con un unico salto, anche se l'andatura media è di 1,2-1,9 m[2][3].

I maschi possono raggiungere una lunghezza di 1,3-1,6 m, ai quali vanno aggiunti altri 1,2 m di coda. Le femmine sono notevolmente più piccole, con una lunghezza del corpo di 85-105 cm e una coda di 65-85 cm[3][4]. Le femmine pesano tra i 18 e i 40 kg, mentre i maschi generalmente pesano circa il doppio, potendo raggiungere tra i 55 e i 90 kg[4][5]. In posizione eretta, un canguro rosso misura circa 1,5 m di altezza alla sommità della testa[6]. I maschi più grandi, comunque, possono superare gli 1,8 m di altezza: l'esemplare più grande di cui sono state confermate le dimensioni era alto circa 2,1 m e pesava 91 kg[5].

Il canguro rosso mantiene la temperatura interna in un punto di omeostasi di circa 36 °C grazie a tutta una serie di adattamenti fisici, fisiologici e comportamentali. Tra questi ricordiamo uno strato di pelliccia isolante, l'abitudine di essere meno attivo e rimanere all'ombra quando le temperature sono più elevate, nonché il rinfrescarsi ansimando, sudando e leccandosi gli arti anteriori.

Grazie alla posizione dei suoi occhi, il canguro rosso ha un campo visivo di circa 300° (precisamente di 324° con circa 25° di sovrapposizione)[7].

Biologia

Mentre il record mondiale di salto in alto per l'uomo è di 2,45 m e quello di salto in lungo è di 8,96 m, il canguro può elevarsi fino a 3,3 m in altezza e spingersi oltre 9 m in lunghezza. Questo marsupiale, tuttavia, si esibisce in tali prestazioni solo in caso di estrema necessità, per esempio quando deve fuggire, in campo aperto, da un predatore. Di solito, invece, se si deve spostare per andare ad abbeverarsi o soltanto per avvicinarsi a un suo simile, si limita a compiere salti inferiori ai 2 m di lunghezza. Quando procede con la sua andatura prettamente bipede (zampe posteriori), il canguro sembra rimbalzare sul suolo e scattare in alto come una molla. Tale tipo di spostamento può raggiungere i 20 km orari, ma, in caso di pericolo, questo animale è in grado di lanciarsi anche a velocità superiori. Quando bruca, il canguro si tiene di solito proteso in avanti e si sposta molto lentamente servendosi di tutti e quattro gli arti, un po' come si muove il coniglio. Esso poggia le zampe anteriori sul suolo e attira la coda a sé, lasciando che le zampe posteriori basculino liberamente. In questa posizione, il peso si sposta sulla parte posteriore del corpo e sulla coda, che funge per così dire da «quinta zampa». Questo tipo di locomozione quadrupede, basato sulla successione di quattro movimenti distinti, sembra esiga un quantitativo di energia di gran lunga superiore a quello necessario per il salto. Studi effettuati per calcolare il consumo energetico di un canguro in movimento hanno dimostrato che, quando il grande marsupiale si sposta a una velocità inferiore ai 18 km orari, impiega più energia di un animale dello stesso peso che corra a quattro zampe. Al contrario, quando accelera, il canguro consuma meno ossigeno grazie a un meccanismo fisiologico favorito dalle fasce muscolari molto elastiche.

Behaviour

Red kangaroos live in groups of 2–4 members. The most common groups are females and their young.[8] Larger groups can be found in densely populated areas and females are usually with a male.[9] Membership of these groups is very flexible, and males (boomers) are not territorial, fighting only over females (flyers) that come into heat. Males develop proportionately much larger shoulders and arms than females.[10] Most agonistic interactions occur between young males, which engage in ritualised fighting known as boxing. They usually stand up on their hind limbs and attempt to push their opponent off balance by jabbing him or locking forearms. If the fight escalates, they will begin to kick each other. Using their tail to support their weight, they deliver kicks with their powerful hind legs. Compared to other kangaroo species, fights between red kangaroo males tend to involve more wrestling.[11] Fights establish dominance relationships among males, and determine who gets access to estrous females.[8] Alpha males make agonistic behaviours and more sexual behaviours until they are overthrown. Displaced males live alone and avoid close contact with others.[8]

Reproduction

The red kangaroo breeds all year round. The females have the unusual ability to delay birth of their baby until their previous Joey has left the pouch. This is called embryonic diapause. Copulation may last 25 minutes.[11] The red kangaroo has the typical reproductive system of a kangaroo. The neonate emerges after only 33 days. Usually only one young is born at a time. It is blind, hairless, and only a few centimetres long. Its hind legs are mere stumps; it instead uses its more developed forelegs to climb its way through the thick fur on its mother's abdomen into the pouch, which takes about three to five minutes. Once in the pouch, it fastens onto one of the two teats and starts to feed. Almost immediately, the mother's sexual cycle starts again. Another egg descends into the uterus and she becomes sexually receptive. Then, if she mates and a second egg is fertilised, its development is temporarily halted. Meanwhile, the neonate in the pouch grows rapidly. After approximately 190 days, the baby (called a joey) is sufficiently large and developed to make its full emergence out of the pouch, after sticking its head out for a few weeks until it eventually feels safe enough to fully emerge. From then on, it spends increasing time in the outside world and eventually, after around 235 days, it leaves the pouch for the last time.[12] While the young joey will permanently leave the pouch at around 235 days old, it will continue to suckle until it reaches about 12 months of age. A doe may first reproduce as early as 18 months of age and as late as five years during drought, but normally she is two and a half years old before she begins to breed.[13]

The female kangaroo is usually permanently pregnant, except on the day she gives birth; however, she has the ability to freeze the development of an embryo until the previous joey is able to leave the pouch. This is known as diapause, and will occur in times of drought and in areas with poor food sources. The composition of the milk produced by the mother varies according to the needs of the joey. In addition, red kangaroo mothers may "have up to three generations of offspring simultaneously; a young-at-foot suckling from an elongated teat, a young in the pouch attached to a second teat and a blastula in arrested development in the uterus".[11]

The kangaroo has also been observed to engage in alloparental care, a behaviour in which a female may adopt another female's joey. This is a common parenting behaviour seen in many other animal species like wolves, elephants and fathead minnows.[14]

Relationship with humans

The red kangaroo is an abundant species and has even benefited from the spread of agriculture and creation of man-made waterholes. However competition with livestock and rabbits poses a threat. It is also sometimes shot by farmers as a pest although a "destruction permit" is required from the relevant state government.

Kangaroos dazzled by headlights or startled by engine noise often leap in front of vehicles, severely damaging or destroying smaller or unprotected vehicles. The risk of harm to vehicle occupants is greatly increased if the windscreen is the point of impact. As a result, "kangaroo crossing" signs are commonplace in Australia.

Commercial use

Like all Australian wildlife, the red kangaroo is protected by legislation, but it is so numerous that there is regulated harvest of its hide and meat. Hunting permits and commercial harvesting are controlled under nationally approved management plans, which aim to maintain red kangaroo populations and manage them as a renewable resource. Harvesting of kangaroos is controversial, particularly due to the animal's popularity.[13]

In the year 2000, 1,173,242 animals were killed.[15] In 2009 the government put a limit of 1,611,216 for the number of red kangaroos available for commercial use. The kangaroo industry is worth about A$270 million each year, and employs over 4000 people.[16] The kangaroos provide meat for both humans and pet food. Kangaroo meat is very lean with only about 2% fat. Their skins are used for leather.

Note

- ^ (EN) Ellis, M., van Weenen, J., Copley, P., Dickman, C., Mawson, P. & Woinarski, J. 2016, BlackPanther2013/Sandbox/kakapo, su IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Versione 2020.2, IUCN, 2020.

- ^ Red Kangaroo – Zoos Victoria, su zoo.org.au, www.zoo.org.au. URL consultato il 16 aprile 2009 (archiviato dall'url originale il 14 luglio 2008).

- ^ a b M. Yue, Macropus rufus, su Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu, 2001. URL consultato il 25 settembre 2015.

- ^ a b Red kangaroo videos, photos and facts – Macropus rufus, su ARKive. URL consultato il 25 settembre 2015.

- ^ a b Gerald Wood, The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats, 1983, ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- ^ P. Menkhorst e F. Knight, A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia, Melbourne, Offord University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-19-555037-4.

- ^ Red Kangaroo Fact Sheet, su library.sandiegozoo.org. URL consultato il 4 ottobre 2015.

- ^ a b c Errore nelle note: Errore nell'uso del marcatore

<ref>: non è stato indicato alcun testo per il marcatoreTyndale 2005 - ^ Johnson, C. N., Variations in Group Size and Composition in Red and Western Grey Kangaroos, Macropus rufus (Desmarest) and M. fulignosus (Desmarest), in Australian Wildlife Research, vol. 10, 1983, pp. 25–31, DOI:10.1071/WR9830025.

- ^ Jarman, P., Mating system and sexual dimorphism in large, terrestrial, mammalian herbivores, in Biological Reviews, vol. 58, n. 4, 1983, pp. 485–520, DOI:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1983.tb00398.x.

- ^ a b c McCullough, Dale R. and McCullough, Yvette (2000) Kangaroos in Outback Australia, Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11916-X.

- ^ Evolution of Biodiversity, BCB705 Biodiversity, University of the Western Cape

- ^ a b Vincent Serventy, Wildlife of Australia, South Melbourne, Sun Books, 1985, pp. 38–39, ISBN 0-7251-0480-5.

- ^ Riedman, Marianne L., The Evolution of Alloparental Care in Mammals and Birds, in The Quarterly Review of Biology, vol. 57, n. 4, 1982, pp. 405–435, DOI:10.1086/412936.

- ^ National commercial Kangaroo harvest quotas, su environment.gov.au, www.environment.gov.au. URL consultato il 16 aprile 2009 (archiviato dall'url originale il 6 June 2011).

- ^ Kangaroo Industry Assocn of Australia – Background Info, su kangaroo-industry.asn.au, www.kangaroo-industry.asn.au. URL consultato il 16 aprile 2009.